On November 21, 1920, Michael Collins' squad "The Twelve Apostles" killed 14 British Secret Service Agents - a day that has gone down in history as "Bloody Sunday."

On the morning of November 21, 1920, at precisely 9 am, agents of Michael Collins’ Squad — aka “The Twelve Apostles” —spread throughout Dublin City and went to work.

When they were finished, 14 British Secret Service agents were dead and the legend of “Bloody Sunday” was written—in British blood—in the annals of Irish history.

But just how did Bloody Sunday come about?

The answer and the origins go back to early 1917 when Collins returned to Dublin from the Frongoch prison camp in Wales and was appointed head of the National Aid and Volunteers Dependants Fund by Kathleen Clarke, the widow of 1916 martyr Tom Clarke. In this position (the office was at #10 Exchequer Street and the building is still there), Collins gave out grants to the indigent survivors of the Easter Rising. He was also the point man to many in the movement—the man with the money—whether they were located in Dublin City or scattered throughout the countryside. This allowed Collins to keep his hand on the pulse of revolutionary Ireland as few men could.

One of the colorful details of Collins’ life was his sojourn into the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) station in Great Brunswick (now Pearse) Street. There he found, among other things, a telephone log of people who called the police during Easter week. He was surprised to note that a lot of the people in the log were supposed to be “friends” of the movement.

Since 1798, the Irish have been having uprisings and all of them have ended in failure. Every movement had been scuttled by the British using 1) superior intelligence; and 2) informers. In the years between 1917 and 1919, Collins addressed these two points of British success and thought how he might counter them. Collins’ greatest teacher? Ironically, it was the British themselves.

His first act was to set up his own intelligence office at #3 Crow Street, a small alley in Temple Bar running off Dame Street, only two blocks from Dublin Castle. There, under the disguise of the “Irish Products Company,” Collins’ intelligence officers, under the command of Liam Tobin, went to work. There they went through newspapers, paying special attention to the social columns, learning who was in town and what their business was. These agents also made contact with people who worked in the railroad, ferry, taxi, and hotel industries, keeping an eye on travelers from either rural Ireland or England. It became a superb way to keep track of enemy agents.

Collins also was able to burrow his way into the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) with the help of RIC men Ned Broy, Dave Neligan, Joseph Kavanagh, and James McNamara. As these “G-men”—so-called because they belonged to the intelligence or “G-Division” of the DMP—typed up their reports, they threw in an extra carbon which was promptly delivered to Collins’ intelligence shop in Crow Street.

De Valera Leaves for America—and the “Squad” is Born

By 1919, Collins had a pretty good idea of what the British were doing and how he wanted to combat them. In May of that year, Éamon de Valera left Ireland for 20 months in America, ostensibly to make Ireland’s case to the world and raise funds. It was an odd decision on de Valera’s part in the middle of a revolution considering he had just been elected Príomh-Aire, First Minister or Prime Minister, of the Dáil. (When Dev checked into the Waldorf-Astoria in New York he signed the ledger as “President” of the Irish Republic, thus making up a new august, albeit fraudulent, title for himself.)

De Valera’s departure left a vacuum in Dublin which was immediately occupied by Collins. Collins’ portfolio included being a TD in the Dáil, the Minister for Finance, Commandant General of the IRA, head of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), and most importantly, Director of Intelligence of the IRA. (He also shamelessly poached Cathal Brugha’s portfolio as Minister for Defence.) He was a compartmental genius and with so many hats to wear, he had to be.

In September of 1919, Collins decided to establish a “Squad”—also known as an Active Service Unit (ASU)—to combat the British. This Squad—soon known as “The Twelve Apostles”—was under the direct command of Collins (and in his absence Richard Mulcahy, Chief of the Staff of the IRA, and Richard McKee, commander of all the Dublin IRA brigades).

Collins's plan was simple—he would warn aggressive G-men to get out or there would be consequences. If they ignored the warning they would be roughed up and if they still remained obdurate they would be shot. Collins's belief was that the brains of intelligence agents—and the knowledge they contained—was impossible to replace. Important information and details would be lost forever, handicapping British intelligence.

Many took the hint and got out. One did not. Detective Sergeant Patrick Smyth had been playing with the rebels since 1916. In fact, his persistence had put Collins’ friend (and future biographer) Piaras Beaslaí behind bars.

Collins sent the Squad to Drumcondra to shoot Smyth. Smyth started running away and the Squad shot him from afar. It took three weeks for Smyth to finally die. Immediately, Collins changed the game. From then on there would be only “head” shots. He also decreed that the Squad should use the heaviest caliber weapons they could find, preferably .45s.

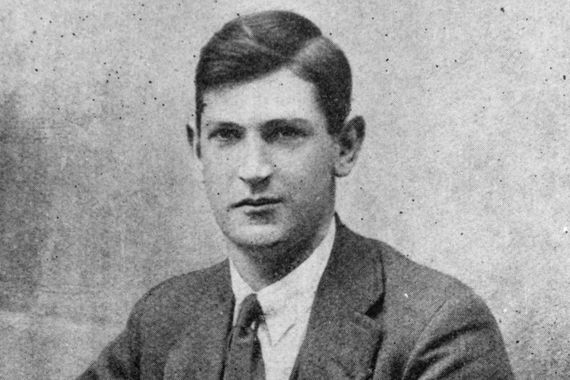

Michael Collins.

None of the shootings were random and the Squad had strict orders not to shoot ordinary policemen. Often, these coppers were friendly to the cause and actually helped the rebels. (It was not unusual for a DMP to salute Collins as he crossed O’Connell Street or, as Dan Breen related in his autobiography, supply bullets for the cause.) A member of the Squad could only shoot in his own self-defense.

Collins also instituted that the Squad would work in teams, a shooting team (of two or four) and a backup team of an equal number, who made sure there was no civilian interference and ensured that the shooting team would escape.

Early in 1920, there were two spectacular shootings. The first was of a British agent (ironically) named “Jameson.” Jameson arrived in Dublin and immediately sought out Collins to sell him badly needed guns. Now the British had been searching manically for Collins and were impressed that Jameson had been able to contact him so easily. He reported to his British handlers in Dublin Castle that Collins was even wearing a mustache! This was relayed to the G-men searching for Collins. Unfortunately for the British one of the G-men worked for Collins and the mustache quickly came off. Soon thereafter Collins got his guns off Jameson—and sent the Squad after Jameson. He was taken to Grangegorman and told his fate. His final words were “God bless the King. I would love to die for him.” The Squad granted his wish.

One of the most spectacular shootings was that of Alan Bell, a man who had been playing with Fenians since the time of the Land League. He was sent to Dublin in 1920 to unearth funds from Collins’ National Loan. When £18,000 was confiscated from a Dublin bank, Collins decided it was time for Mr. Bell to cease breathing. He was pulled off a tram on his way to work at Dublin Castle and shot dead in April 1920. Thereafter the British had trouble getting bank examiners to come to Dublin to look at the books

London was alarmed and the Secretary of State for War, one Winston Churchill, signed off and soon the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans would hit Irish soil. Churchill also put a £5,000 (sometimes embellished to £10,000) bounty on the head of the man responsible for the death of Bell—that man, of course, being Michael Collins. The Mick Collins legend was growing.

A Black October Leads into Bloody Sunday

By October 1920, the war reached a fever pitch as two intelligence services went after each other in the streets of Dublin.

On October 14, the British found Tipperary IRA fugitive, Seán Treacy, at the Republican Outfitters at 94 Talbot Street (the building is marked today by a plaque). A raging gun battle took place in the middle of the street and Treacy was killed.

Elsewhere, Treacy’s great friend and fellow Tipperary man, Dan Breen, was badly shot up and surreptitiously smuggled into the Mater Hospital where the medical staff not only saved his life but kept him hidden from the British as well.

On October 25, Terence MacSwiney, the republican Lord Mayor of Cork starved himself to death in Brixton Prison in England after a fast of 74 days. His body was returned to Cork City on Halloween as the British frantically searched for Collins at MacSwiney’s funeral.

But Collins was not in Cork, he was in Dublin trying to figure out a way of breaking Kevin Barry out of Mountjoy Gaol. Barry was an 18-year-old medical student and part-time IRA volunteer. On September 20, he was involved in an ambush at Church and North King Streets in Dublin. He did not realize that his comrades had withdrawn and was captured by the British. During the ambush, a young British soldier was killed and Barry was condemned to death by rope. The clueless British picked November 1, All Saints Day, a Holy Day of Obligation to Dublin’s immense Catholic population, to hang Barry—and another legend was born.

I have speculated before that Collins was bipolar, capable of tremendous highs and lows. I believe in this period he was depressed by the loss of so many friends, the near-death of Breen, and the feeling that the British were closing in on him and his men. I think that this feeling of impending doom forced Collins to take drastic steps to stop the British who were importing intelligence agents from all over the empire, particularly the Middle East. These agents were nicknamed “The Cairo Gang” either because they came from Egypt or they hung out at the Cairo Café at the top of Grafton Street. The picture was ominous—kill or be killed. I believe this snapped Collins out of his depressive state and started the planning for Bloody Sunday.

By sheer luck, a young maid named Rosie had come across a list of names of British intelligence agents and—after much persuading—turned them over to Collins.

On Wednesday, November 17, 1920, Collins sent the following memo to Dick McKee, head of the Dublin brigades: “Have established addresses of the particular ones. Arrangements should now be made about the matter. Lt. G is aware of things. He suggests the 21st, a most suitable date and day I think. M.”

It was going to be a big job, a job too big for the Squad to handle by itself. So members of the Dublin Brigade were called in to supplement the Squad. One of these volunteers was Seán Lemass—a future Taoiseach of Ireland—who would do his handiwork in Baggot Street. That morning, many of the IRA men first went to mass at St. Andrew’s in Westland Row, or John Cardinal Newman’s University Church in St. Stephen’s Green before spreading out into what is now the posh Dublin 4 postal code to do their duty.

The 14 executions panicked the British. Intelligence agents and their families jammed the entrance to Dublin Castle to escape what they thought were more imminent executions. The Black and Tans opened fire at a Dublin v Tipperary football match in Croke Park where another 14 were killed, including a footballer, Michael Hogan.

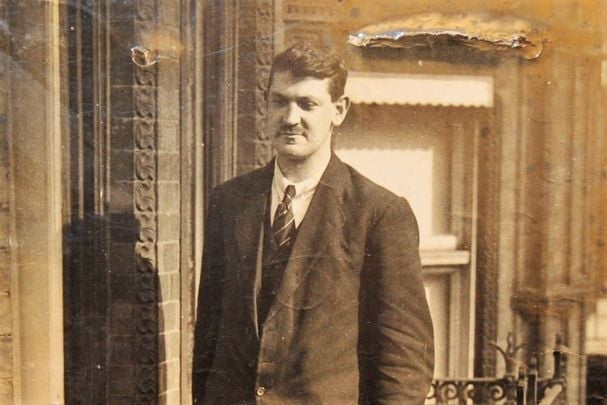

Michael Collins throwing in the ball to start a hurling match at Croke Park, Dublin in 1921. (Getty Images)

Back at Dublin Castle, McKee and Peadar Clancy, brigadier and vice-brigadier of the Dublin Brigades, captured the night before with the help of tout Shankers Ryan, were murdered along with a Gaelic Leaguer up from the country by the name of Conor Clune.

It was at this time the world saw Michael Collins as his most fearless. The next morning, with everyone in Dublin looking for him, he kept a promise and attended a wedding reception. He then personally dressed the bodies of McKee and Clancy in the Mortuary Chapel of the Pro-Cathedral, before attending the funeral mass.

At the mass, he pinned a personal note on McKee’s coffin: “In memory of two good friends—Dick and Peadar—and two of Ireland’s best soldiers.” It was signed Mícheál Ó Coileáin.

For all intent purposes, the war was over. Michael Collins knew it and so did Prime Minister David Lloyd George, but atrocities would go on for another seven months until King George V brokered a truce in July 1921.

Dev Returns, General Collins Goes to London

The most immediate reaction to the slaughter—the dirty work now over—was the return of Eamon de Valera to Ireland at Christmas 1920. He immediately began to minimize Collins with the help of Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack. It was another dark period in the life of the Big Fellow. That would come to an end when de Valera abdicated going to London in the fall of 1921 to work out a Treaty with the British. De Valera knew it was an impossible lose-lose situation for him—so who better to send than Michael Collins?

At the time of Bloody Sunday, Collins had less than two years to live, but he was adamant in what his men had done on that fateful day: “My one intention was the destruction of the undesirables who continued to make miserable the lives of ordinary decent citizens. I have proof enough to assure myself of the atrocities which this gang of spies and informers have committed. If I had a second motive it was no more than a feeling such as I would have for a dangerous reptile. By their destruction, the very air is made sweeter. For myself, my conscience is clear. There is no crime in detecting in wartime the spy and the informer. They have destroyed without trial. I have paid them back in their own coin.”

Do the ends justify the means?

Just 12 months and 16 days after Bloody Sunday, on December 6, 1921, Collins signed the Treaty which, after 700 years of occupation, returned Ireland to nationhood.

Without this terrible day in Irish history—perhaps the most important day in Irish history—there is a great possibility that the Union Jack might still be flying over the GPO on O’Connell Street. Young Irelander Thomas Davis only dreamed of “A Nation Once Again,” but Michael Collins, a revolutionary genius not afraid to use the ruthless brutality that the British had applied to Ireland over seven centuries, made it happen.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," both now available in paperback, Kindle, and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected], his website, and Facebook page.

*Originally published in 2015, updated in November 2023.

Comments