Kathleen Daly Clarke, Irish patriot, founder member of Cumann na mBan, and the first female Lord Mayor of Dublin, died on this day in 1972. She was the wife of Easter Rising leader Thomas Clarke and sister of fellow Irish revolutionary Ned Daly.

Editor's note: This article, originally published in 2016, examines the key moments that defined Thomas Clarke's life and why he is such an important figure in Irish history. It also touches on the legacy of his wife Kathleen.

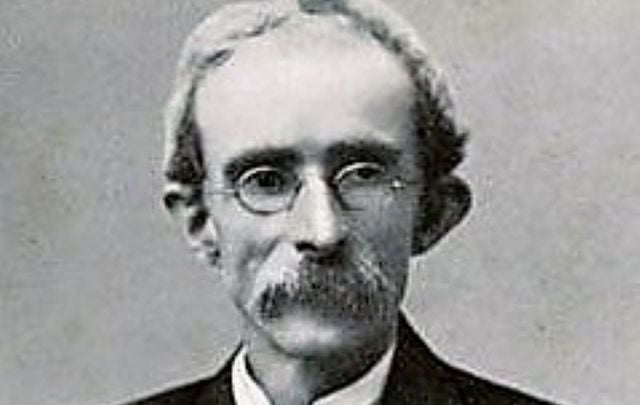

Thomas J. Clarke, a key member of the Irish revolutionary and a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. was among the rebel leaders executed on May 3, 1916.

He was born in 1858 on the Isle of Wight but grew up in County Tyrone.

At age 20 he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and his career as an indefatigable Irish revolutionary began. After a skirmish with police, he was forced to flee to America where he became a citizen of the United States in the City of Brooklyn in 1883. (He was the only American citizen involved in the 1916 Rising executed by the British.)

Thomas J Clarke: an incorrigible Irish revolutionary. Credit: Public Domain

In that same year, he heeded the call of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and returned to England on a secret mission – to blow up London Bridge. He was apprehended and spent the next 15 years in British prisons.

At Millbank Prison, he was Prisoner J464 and was treated brutally:

“I remembered with what relentless savagery the English Government had always dealt with the Irishman it gets into its clutches, and the future appeared as black and appalling as imagination could picture it.”

Upon his release, he returned to New York. There he married Kathleen Daly – of the radically Republican Daly family of Limerick – in 1901. John MacBride was his best man and John Devoy, who Pearse called “the greatest of the Fenians,” was also in the wedding party. The Clarkes lived all over New York City and Long Island as Tom was employed at various jobs, including working for Devoy on the Gaelic American newspaper.

In 1907 he decided, with unrest between the European superpowers becoming apparent, it was time to return to Ireland. He opened several newsagent stores, the most prominent one being on the corner of Sackville (now O’Connell) and Great Britain (now Parnell) Streets, directly across from the Parnell Monument. It became a prime meeting place for every prominent Fenian leader of the coming revolution.

Clarke became the Fenian pied-piper and brought such young men as Seán MacDiarmada, Padraig Pearse, Joseph Mary Plunkett, and Thomas MacDonagh into his Fenian sphere of influence. He even influenced the young Michael Collins.

“It was in 1914, just before the declaration of war, that the chance came to take passage to New York,” Collins is quoted in Hayden Talbot’s "Michael Collins' Own Story." Collins went on to state that “…when I laid the scheme before Tom Clarke…he advised me not to go. His reason satisfied me. He said there was going to be something doing in Ireland within a year. That was good enough for me. I changed my mind about going to America, and plodded along in my uncongenial job [in London].”

Britain’s entry into the Great War in 1914 presented a unique opportunity for Clarke and the radical IRB. With the advent of war, John Redmond of the Irish Parliamentary Party had urged Irishmen to join the fight for Britain. This had caused a split in the Irish Volunteers and Clarke and his group of young revolutionaries moved in to fill the void.

By 1915 planning for a rebellion was underway. Sir Roger Casement and Plunkett traveled to Germany to try and raise arms for the rebellion. Early in 1916 James Connolly and his Irish Citizen Army were brought into the conspiracy.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

The Rising was initially set for Easter Sunday 1916, but things went wrong from the start. Eoin MacNeill, the nominal leader of the Volunteers, was kept in the dark about what was happening, and when he learned that the “maneuvers” were actually a march to insurrection he countermanded the order. The Rising was then moved to Easter Monday, but the revolt had been stripped of much of its impact.

On Easter Monday Clarke’s name was the top signature on the Proclamation and, as a mark of admiration and honor, he was the first to march into the GPO to take over the building. On Friday, with the GPO engulfed in flame, Clarke led his men out across Henry Street and into buildings on Moore Street where the rebels made their last stand.

After the surrender, Clarke was bivouacked for the night with the rest of the rebels in the garden of the Rotunda Maternity Hospital. There, according to reports, he was stripped naked by Captain Percival Lea Wilson and beaten. (Michael Collins witnessed this and had Wilson shot dead in Gorey, County Wexford, three years later.) From there, Clarke was transported to Richmond Barracks for court-martial, found guilty, and transported to Kilmainham Gaol for execution.

Unlike Pearse and MacDonagh whose families could not visit in time, Clarke was able to say goodbye to his wife, Kathleen. According to her autobiography, "Revolutionary Woman," he told her his trial had been a “farce.” He then told her, “I suppose you know I am to be shot in the morning. I am glad I am getting a soldier’s death.” Kathleen wrote, “he faced death with a clear and happy conscience.”

But the old Fenian wasn’t finished yet. He railed against Eoin MacNeill who had countermanded the maneuvers for Easter Sunday. “To send out countermanding orders secretly,” Clarke told his wife, “giving us no hint of what he was doing, was despicable, and to my mind dishonorable.” Just hours before he was executed Clarke gave this command to his wife: “I want you to see to it that our people know of his treachery to us. He must never be allowed back into the National life of the country, for so sure as he is, so sure will he act treacherously in a crisis. He is a weak man, but I know every effort will be made to whitewash him.”

This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe now!

Kathleen Clarke may have suffered more than any other survivor of the Rising. She not only lost her husband, but also her brother, Ned Daly, the commandant in charge of the Four Courts.

In addition, she was pregnant at the time of the Rising. “A baby was coming to us,” wrote Kathleen, “but [Tom] did not know. I had not told him before the Rising, fearing to add to his anxieties, and considered if I could tell him then but left without doing so.” Her final tragedy of 1916 was to miscarry that baby. Besides his widow, Clarke was survived by sons Emmet, John Daly, and Tom Jr.

Kathleen Clarke was to carve out a Republican reputation of her own. In 1917 she appointed the young rebel her husband had persuaded not to go to America – Michael Collins – as director of the National Aid and Volunteers Dependents Fund, a charity for indigent survivors of the Rising. Starting with that position Collins was to go on and strike fear into the hearts of the British establishment. During the War of Independence, she served as a judge in the Republican courts and was elected to the Dáil.

In 1939, she became the first woman to become Lord Mayor of Dublin. One of her first official acts was to remove a portrait of Queen Victoria. She died in 1972 at the age of 94. She outlived her husband by 56 years.

~~~~~

* Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook here.

* Originally published in 2016, updated in September 2024.

Comments