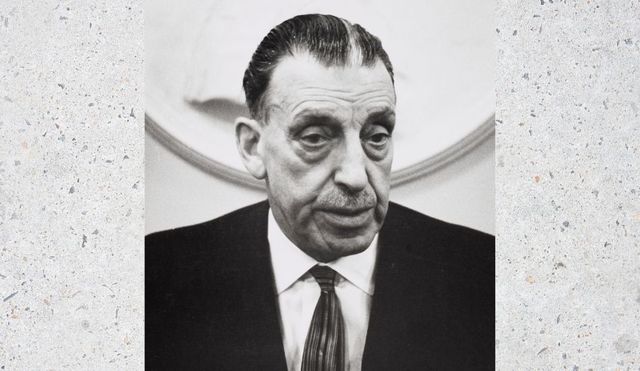

When President Kennedy visited Ireland in June 1963 he was accompanied on many of his appearances by the Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Seán Lemass. Lemass (1899-1971) was a pivotal figure in Irish history, a human bridge from revolutionary Ireland to the present Ireland of the European Community.

Lemass was known for his economic expertise. During World War II (the “Emergency” as it was euphemistically known in the Free State) he was the Minister for Supplies, keeping Ireland afloat in such essentials as petrol and coal.

Under Eamon de Valera, he was the long-serving Minister for Industry and Commerce. It was under this portfolio that he helped establish such staples of the Irish economy as the national airline, Aer Lingus (essential to tourism), and Ardmore Studios in County Wicklow, which made Ireland an international movie-making destination.

Many thought that Lemass should have become Taoiseach (Prime Minister) right after World War II, but de Valera would not let go of power. It was not until de Valera was elected President in 1959 that Lemass was elevated to Taoiseach. His seven-year term was marked by promoting many of the young backbenchers like Jack Lynch and his son-in-law, Charles Haughey—both future Taoisigh—to positions of responsibility as he pushed some of the anachronistic revolutionary TDs to the back of the Dáil.

Read more

His term was historical in that he became the first Taoiseach, in 1965, to travel to the north to meet with the Northern Ireland premiere, Terence O’Neill. Seán Lemass—whose life was scarred by the tragic murder of his brother Noel by Free State combatants in 1923—became known as the revolutionary who sought peace for his country.

The Taciturn Revolutionary and Bloody Sunday

Lemass, as a 17-year-old, was in the General Post Office in 1916. In Ireland being a part of the revolutionary experience was a godsend for politicians. Being in the GPO in 1916 was worth votes in any constituency. So it is surprising that Seán Lemass was that unique Irish politician who didn’t want to brag about his wartime service. In fact, he did his best to cloud his participation in many of the seminal events of his country.

And perhaps the most important event that led to the establishment of the modern Irish state were the shootings which occurred on the morning of November 21, 1920, known in Irish history as “Bloody Sunday.”

On that morning, agents of Michael Collins’s assassination Squad (renowned in Irish lore as “The Twelve Apostles”—presumably making Collins their Jesus Christ) murdered 14 British Secret Service agents in their beds. That afternoon the Black and Tans turned machine guns on innocent civilians at a football match at Croke Park resulting in another 14 deaths.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

After 700 years of occupation, Collins’s ruthlessness broke the British will to occupy most of Ireland and a mere 12 months and sixteen days after Bloody Sunday Collins signed the Treaty that established the Irish Free State, the forerunner to today’s Irish Republic.

The question that had remained muted for nearly a century still demands an explanation—what was Seán Lemass’s part in the events of Bloody Sunday? Thanks to the Irish Army, we now have some answers.

Military Service Pensions Collections

In anticipation of the centennial of the Easter Rising in 2016, Óglaigh na hÉireann, the Defence Forces Ireland, has begun publishing applications for pensions for those involved in the War of Independence and Irish Civil War, covering the years between 1916 and 1923. (You can search the database at www.militaryarchives.ie.

Read more

In 1942 Lemass applied for a pension. (He was awarded one for £99 per annum.) In his witness statement, he declares that he was in the GPO in 1916 and for a time was held prisoner with other young rebels at Richmond Barracks. He claims he was held for a month, then released. He also claims to have been sent to the Frongoch prison camp in Wales with other prominent rebels such as Collins—and this appears to be a startling revelation because his biographers never mentioned Frongoch in their writings.

Q: Were you arrested?

A: (by Lemass): Yes, and interned in Frongoch.

Q: When were you arrested?

A: (by Lemass): At the surrender, and sent to Richmond Bks., for a month and then released.

(These statements appear on Page 40)

One wonders if this was fantasy or pure embellishment on Lemass’s part, puffing up his rebel resume. This is hard to believe because of Lemass’ reputation for integrity. Perhaps it was a misunderstanding or a typist/transcription error that “Frongoch” was mentioned at all. Maybe Lemass said “Richmond” and “Frongoch” was typed in its stead. His principal biographer, John Horgan, states: “Lemass was one of the lucky ones, picked out by a DMP [Dublin Metropolitan Police] policeman who knew the family and who suggested to the British officer responsible for planning the deportation process that the lad was only a ‘nipper’ and should be sent home. ‘He was old enough to handle a rifle,’ the officer retorted, but he relented; Lemass was released.”

In fact, in the 1916 Rebellion Handbook which has many articles and lists from the Irish Times of 1916, on page 90 under a list of those released from Richmond Barracks on Wednesday, May 24, 1916, is one “Lemass, John, Dublin.” The facts surrounding Lemass’ imprisonment is the first surprise. There are more.

Lemass never wanted to talk about Bloody Sunday. It might have something to do with politics—Lemass was a de Valera man, not a Michael Collins man. In fact, Lemass admits in Judging Lemass by Tom Garvin that he didn’t know Collins well: “I met him, but I did not know him. He was far above my rank in those days.”

Lemass was notoriously tight-lipped about his participation that November morning. In Seán Lemass: The Enigmatic Patriot by John Horgan, he doesn’t want to talk about it and has one of the great lines in Irish revolutionary history about the events of that day: “Firing squads don’t have reunions."

In the recent Judging Lemass, his service that morning is brushed away by author Garvin. “Lemass,” says Garvin, “name is not on any list of named members of Collins’s squad; there are at least seventeen such names, as some people moved in and out of the list of the dozen or so active members…However, Lemass was on active duty that day with his IRA battalion, so at a minimum, it can be inferred that he did escort duty [my italics] for one of the killers.”

Garvin says he doubts Lemass was in the Squad. And Garvin is right, Lemass was not a member of the Squad, but the job on Bloody Sunday—14 killings done, on Collins’s direct orders, simultaneously at 9 a.m. sharp—was so massive that men from the Dublin Brigade were brought in to supplement the Squad. Garvin also seems to have trouble believing that Lemass could be a cold-blooded killer, unlike the regular members of the Squad. Garvin is wrong—as Lemass’s witness statement proves. (The entire statement can be viewed here.)

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Initially, Lemass only says—in his own handwriting—that he was on “service on November 21st.”

Under questioning he goes on:

Q: You had service on 21st November?

A: (by Lemass): The principal thing during that period was 21st November, “Bloody Sunday.” I was in charge of the company. I was arrested on 12 December 1920.

Q: Could you amplify “Bloody Sunday”?

A: (by Lemass): I was in command of the company who was operating.

So Lemass didn’t want to say much but admits to having been in command—not merely being on “escort duty”—of a unit that morning. According to those who have written about the events of Bloody Sunday, especially Collins’s foremost biographer, Tim Pat Coogan, it is generally agreed that Lemass led the team that worked at 119 Lower Baggot Street, about a five-minute walk from St. Stephen’s Green.

I was in touch with one of Collins’s biographers, Colm Connolly of RTE, who was close to Vinny Byrne, one of the prominent members of the Squad. During research for my novel on the Squad, The 13th Apostle, I compiled a list of addresses where the Squad struck that day. I ran them by Connolly and he commented on some, including the events that happened at:

(From my notes, compiled from various publications:) 119 Lower Baggot Street. Subject: Captain G.T. Bagally, one-legged barrister and Courts-Martial Officer. Prosecutor of IRA. Involved in the murder of an innocent businessman named Lynch in a Dublin hotel [Exchange Hotel, Parliament Street] (probably mistaken for IRA General Liam Lynch). Bagally shot dead with five bullets.

From Colm Connolly: “And, according to Coogan, Sean Lemass was part of the raid on 119 Lower Baggot Street, killing Captain Baggelly [Note: there are multiple spellings for this name]. If Lemass took part in this raid, then he crossed the Liffey afterwards with another Squad member, Charlie Dalton.” In fact, Coogan wrote in his Collins biography: “Captain Baggelly, who died at 119 Lower Baggot St., never knew that one of the three-man party which shot him would be a future Irish Taoiseach, Prime Minister Seán Lemass.”

Read more

So Lemass remains taciturn in his witness statement but admits to having been in charge of one of the Baggot Street shootings that morning. (That was an extremely busy area—today’s ritzy Dublin 4 postal code—on Bloody Sunday with another shooting on Baggot Street, one on Upper Pembroke Street, and shootings just blocks away on Upper and Lower Mount Streets, just west of Merrion Square.)

The Charlie Dalton Connection

Charlie Dalton was the younger brother of Emmet Dalton, one of Collins’s generals in the National Army (he was with Collins when he died and would, years later, collaborate with Lemass in setting up Ardmore Studios). Charlie was also a member of Michael Collins’s Squad and took part in the Bloody Sunday shootings.

According to his book, With the Dublin Brigade, and my own independent research, Charlie was involved in the shootings at No. 28 Upper Pembroke Street, just off Lower Leeson Street and about a block from St. Stephen’s Green. Charlie was not a shooter this day; he was an intelligence officer who was supposed to secure as many intelligence papers as he could, but he was so stunned and frightened by the shootings he went away empty handed. This is also the house that “Rosie”—Charlie’s unwitting intelligence mole—worked at as a maid. She makes a cameo appearance in Neil Jordan’s film Michael Collins and was the source of intelligence for many of the killings that morning.

My notes on 28 Upper Pembroke Street indicate that this was a boarding house managed by the matronly Mrs. Grey. The Squad used a “plumber” to case the house. Subjects: Major Dowling (officer of the Grenadier Guards) and Leonard Price, M.C., Middlesex Regiment. This is “Rosie’s” house. [Also mentioned by Dalton in his book.] Nine assassins. The squad used Rosie as a ruse to Dowling: “I have a letter for you, sir.” Dowling shot dead. Price shot dead. Colonel Woodcock got in the way and was shot. Colonel Montgomery shot. Captain Keenlyside—his wife made a fuss—shot in arm. Lieutenant Murray wounded on way out. Rosie later said, “Oh, why did you do that to them, I thought you would only kidnap them and send them away.”

Recently, Dalton’s eponymous book, With the Dublin Brigade, was reissued by the Mercier Press in Ireland. The book is the exciting story of the 17-year-old Dalton and his work for Collins. After the attacks on Bloody Sunday, Dalton suffered a mental breakdown (as several other members of the Squad did). Dalton was a Collins man to the end and pro-Treaty. Lemass was a de Valera man and anti-Treaty. As the years wore on Dalton sought pension relief while a patient at Grangegorman Mental Hospital in Dublin. Considering that they were on opposite sides during the Civil War Lemass was very generous to Dalton. At the request of Dalton’s wife Theresa, in 1942 he handwrote a five-page letter on his government stationery (Office of the Minister for Supplies) seeking to help Dalton obtain a disability pension.

This letter is extraordinary because it calls into question many of the things historians believed about the events of Bloody Sunday. As Colm Connolly commented in his email to me, it was taken as fact that many of the rebels, like Lemass and Dalton, headed to the River Liffey and took a ferry to the north side. But Lemass’s letter even brings that theory—which Dalton wrote about in his book—into doubt. Here’s what Lemass wrote about the evening of Bloody Sunday and his connection to Charlie Dalton in his letter to Mrs. Dalton:

“I was associated with your husband the latter part of 1920. At that time, he, I, and some others were lodging together at the Dispensary Building, South William Street. All those lodging there were on active service but not all with the same unit. Your husband, Charles Dalton, was I understood, engaged in intelligence work. He was of highly strung disposition, and on more than one occasion I came to the conclusion that the strain of his work was telling on his nerves. I first became seriously concerned about him, however, on the evening of Sunday, Nov. 21st, 1920 (since called ‘Bloody Sunday’). On the morning of that day, a number of British government agents in Dublin were shot. It was your husband’s duty to accompany a party of IRA to one house occupied by four of these agents, all of whom were shot. He returned subsequently to the billet at S. Williams Street and I realized that he had become unnerved by his experiences of the morning. So obvious was his condition that I and one of the others took him out for a walk although it was an undesirable and risky thing to do and might have drawn attention to the billet. It did not improve his condition and during that night he was, on occasions, to be hysterical.”

(To read the full contents of Lemass’s letter click here. The letter appears on page 66.)

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

How Lemass’s Letter Changes History

One thing you’ll be amazed at when studying Irish revolutionary history is that every story has several versions. In his two witness statements Lemass changes three things in his revolutionary biography: 1) he claims he was imprisoned in Frongoch in Wales, which is either an unlikely embellishment or, perhaps, a transcription mistake; 2) he admits that he was “in command” of an assassination team on Bloody Sunday; and 3) contrary to every historical report he claims he did not cross the Liffey by ferry on Bloody Sunday but remained on the south side of the city, hiding out in South William Street.

Charlie Dalton in his book says he escaped across the River Liffey after the events of Bloody Sunday. Yet Lemass has him on the evening of Bloody Sunday back on the southside of Dublin in South William Street, which is very close to the Gaiety Theatre on South King Street and within a 10-15 minute walk from both Baggot and Upper Pembroke Streets. Why risk crossing the Liffey when you can hide in plain sight? It makes perfect sense that the shooters in the area around St. Stephen’s Green would remain in the area rather than risk capture gallivanting around the city.

And Lemass’s own admission that many of the participants from Bloody Sunday were hiding out at this South William Street billet—further identifies Seán Lemass as one of the shooters of Bloody Sunday.

Read more

Final conclusions

With the release of these witness statements, there can be no doubt that Seán Lemass was, indeed, active as an assassin on the morning of November 21, 1920, in the defense of his country. His comments about Frongoch and South William Street certainly call into questions the true nature of several events which took place during the War of Independence. But it is still refreshing, in an era when gutless politicians like to talk tough without having to confront their own mortality, seeing the courage, growth and generosity of Seán Lemass as he matured from reluctant gunman to peace-seeking patriot.

* Dermot McEvoy is the author of The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising (Skyhorse Publishing).

Comments