Political progress is not smooth and cannot be taken for granted. Sometimes it’s two steps forward, one step back.

It is a process of securing agreements and building for the future. Defending what has been achieved while looking at what has yet to be.

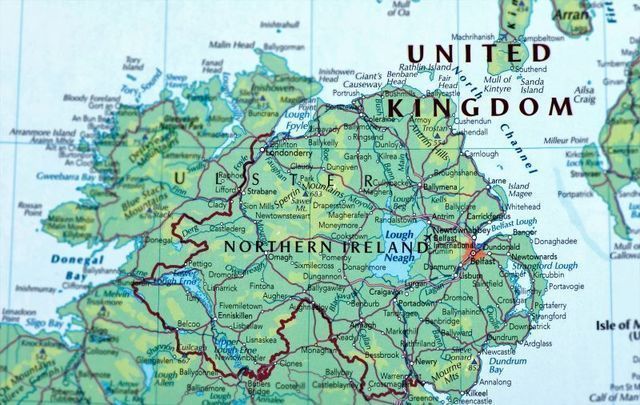

In the fall, we will face two significant challenges to the progress that Ireland has enjoyed since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. Challenges that had been resolved in previous agreements -- Brexit and dealing with the legacy of conflict.

U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, elected on the back of an English nationalist crusade against the EU, now enjoys a safe majority in Westminster. Domestically he is free to pursue his reckless policies.

Brexit, while an economic disaster, has been a vote winner for Johnson. He is determined to continue his battle against his nearest allies and largest market.

In January 2020 he signed into law an international agreement that would prevent a hard border on the island of Ireland. This included the so-called Irish Protocol.

By the end of that year, he had signed another legal agreement with the EU on how this Protocol would be implemented.

Since then, his government undermined these agreements. It has created ongoing uncertainty for business, threatened to collapse the deal and break international law, deepened the anti-EU rhetoric, heightened tensions, and promoted illegal paramilitary loyalist groups. All to keep the pot boiling with the EU.

The cynicism and danger of these actions were called out by President Biden at the G7 summit. He called for agreements to be respected and difficulties resolved within the agreed mechanisms. For the rhetoric to be dialed back, and the threat of unilateral action taken of the table.

The message was clear. Europe was proposing to resolve the issues in line with their agreements. It was Britain who was threatening and heightening the rhetoric.

The next pinch point in the Brexit saga is September 30 when the already extended grace period for implementing the agreement ends. Britain is again provocatively threatening to take unilateral action if there is not a fundamental renegotiation of the agreements.

The EU has indicated that it is open to using the mechanisms of the agreements to resolve matters of implementation but has refused a fundamental renegotiation. Britain is again threatening to breach agreements and international law and not just on Brexit.

Legal actions, inquests, and investigations into the actions of British forces have exposed unjustified killings and collusion with loyalist paramilitaries. Events that were never fully investigated during the conflict and covered up by the state.

The British government now threatens to introduce laws to end all police and ombudsman investigations, inquests, and the right to take civil actions. They are proposing an amnesty to their military and others involved in the conflict.

This approach undermines the human rights of victims and cannot be reconciled with the explicit commitment in the Good Friday Agreement to incorporate the protections of the European Convention on Human Rights into law.

Again, an agreement was in place between all parties and the Irish and British governments to deal with the issue of the past. The Stormont House Agreement, signed in December 2014, has been endorsed by both houses of Congress and the successive administrations.

In January 2020, the British government of Johnson agreed to make the Stormont House Agreement law within 100 days. Three months later, the British government stated that they would not honor their agreement.

The threat to end investigations has been rejected by victims groups, all political parties, the British Labour Party, the Irish government, UN Human Rights experts, and leaders in Congress.

The only criticism from within Johnson's party to these plans was that they were not moving quickly enough.

The British government claims their approach is part of a truth and reconciliation process referencing South Africa. The same British government that has refused to make public their files, failed to implement their agreements, and fought victims at every stage through the courts.

In South Africa, the apartheid regime brought forward a similar plan for an unconditional amnesty. It was rejected by the African National Congress and civic and human rights organizations.

In the South African truth and reconciliation model, amnesty was conditional on full disclosure and a rigorous investigation. When it was being discussed, Lourens du Plessis, then professor of public law at Stellenbosch University wrote about society in general, “For the sake of reconciliation, we must forgive, but for the sake of reconstruction, we dare not forget.” The British government is telling victims to forget while they conduct a coverup.

In the coming months, political capital and energy will be spent defending agreements that should have long ago been implemented. This is a British government that believes that it is not bound by its agreements, obligations, or international law.

The Good Friday Agreement provides a peaceful and democratic pathway to unity. The actions of the British government demonstrate that the best interest of all the people, the economy, and healing is best served in a united Ireland.

We must defend the progress we now all enjoy, but we must also build for a future free from British government duplicity and interference.

It is time to plan and prepare for a new and united Ireland in which prosperity, citizens' rights, and reconciliation cannot be undermined by Westminster. An Ireland that is a home for all the people who share the island.

It is time for the U.S. to look to the future and the full implementation of the Good Friday Agreement including the democratic provision of a unity referendum.

The challenge as always is to defend today and build for tomorrow. Both are essential to secure progress.

*Ciaran Quinn is the United States representative for Sinn Féin

*This column first appeared in the September 1 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

Comments