In 1985, a delegation of Irish American leaders visited the US state department in Washington to seek a policy briefing on Northern Ireland.

The desk officer in charge of Ireland explained to us that he had been given charge of Ireland because it was alphabetically close to Iceland, which was a Nato member and his main priority.

We asked him where his information on Ireland came from, and he opened a drawer and produced a sheaf of clippings, all from right-wing British newspapers, not an Irish newspaper clip among them.

That was the sum total of his knowledge and interest in Ireland.

Our brief meeting over, we stood outside on the pavement and pondered the massive task ahead.

Read more

How would the US ever become responsive and involved in the Irish issue given the derisory attitude we had just experienced?

Yet, less than a decade later, in 1995, I sat in a midtown law office with George Mitchell, the newly appointed special economic envoy to Northern Ireland.

I had expected Mitchell to seek guidance on the alphabet soup of players in Northern Ireland, but I ended up having an education myself as he outlined his vast American political experience as Senate majority leader, cutting deals with friends and foes, and using that template for operating in Northern Ireland.

I left thinking here was the type of pragmatic American approach that could work so well in the North. I also considered Mitchell’s appointment as an achievement hard-won by the Irish American lobby who had long faced criticism for seeking an envoy as the British and indeed often the Irish governments wanted no truck with Irish America.

Work it did, and Mitchell surpassed all expectations to the point where many believe he should have shared the Nobel Prize awarded to John Hume and David Trimble.

In short, the Mitchell intervention was the endgame of a concerted effort by Irish Americans across the political spectrum to make Northern Ireland relevant in American foreign policy. The appointment of Mitchell was one of several major steps Clinton took, including the granting of a visa to Gerry Adams, that transformed the political landscape in Northern Ireland.

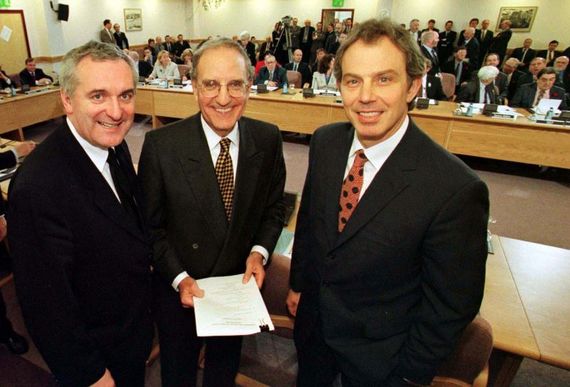

Bertie Ahern, George Mitchel and Tony Blair at the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

Mitchell’s work culminated, of course, in the Belfast Agreement – 23 years old this year – which has overcome every crisis up to now.

But the American involvement must not end there. There is a mood abroad that because Biden is president there is less need for an envoy.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The US envoys after Mitchell, men, and women such as Richard Haass, Paula Dobriansky Gary Hart all provided vital insight and encouragement in handling the difficult issues that arose out of the Good Friday Agreement,

Now with Brexit and a unity poll in Northern Ireland on the agenda, it is no time for America to step back from a day to day involvement no matter who is in the White House.

The need for continued American involvement in Northern Ireland is crystal clear. Only a fool believes the problems in the North ended with the signing of the Belfast Agreement.

If the ramifications of Brexit and a unity referendum cannot be dealt with, they could combine to form the perfect storm and create another major crisis.

Read more

The view that Biden and the Irish government can solve all issues ignores the fact that the envoy represents also the Irish American interest in safeguarding what Mitchel and others accomplished.

Clearly, there is still a role for the US in the quest to utterly normalize the North. Kicking Northern Ireland to the curb as a lack of a US envoy would signal merely emboldens and makes stronger those who are resisting change and compromise.

Northern Ireland needs an American presence, for political and economic reasons. Letting go of such a commitment sends a clear message of disinterest.

Having gained that influence in such a hard-won way, the Irish Government and Irish America should push for a new envoy despite the close relationship with Biden. Too often, as we have seen, the problem can be with the Irish government as Micheal Martin’s dreadful appearance on a recent discussion of Irish unification program on Irish television showed.

Una Mullaly of the Irish Times summed it up well by writing of Martin’s contribution:

“The past, the past, the past. There was no vision for the future among the waffle.

“My view is that I think it’s important that we continue to work together and engage with each other,” he said. Great. Thanks. Hadn’t thought of that one before.”

Indeed. The American role is still vital.

Irish America needs to ensure that a special envoy be appointed to act as a peace guarantor just as Mitchell and others did.

Comments