On this day, May 5, in 1916, Easter Rising leader John MacBride was executed for his role in the rebellion.

The Easter Rising took place over the course of five days in Dublin in 1916 and forever changed the course of Irish history. To commemorate this anniversary, writer and historian Dermot McEvoy produced 16 profiles of the Irish Rebel leaders who were executed one hundred and one years ago and who, gradually, have come to be seen as heroes.

Between May 3 and 14, 1916, 15 leaders of the Rising were court-martialed by the British Army under General John Maxwell and convicted. IrishCentral will look at the leaders - from James Connolly to Joseph Mary Plunkett - and share their stories.

Read more

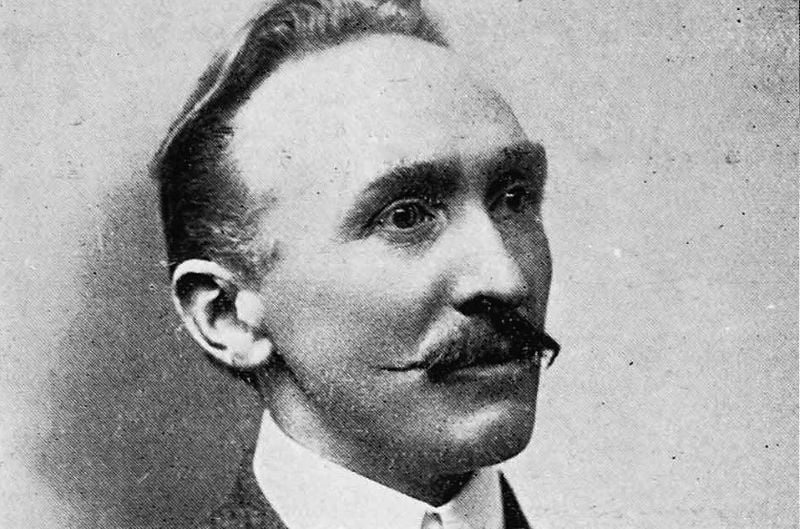

John MacBride

John MacBride was born in County Mayo in 1865, became interested in Irish Republican politics, then left for South Africa to make his fortune in the gold mines. He fought against the British during the Boer War—a point not lost on British General John Maxwell of Easter Rising fame/infamy who was also a participant in the Boer War on the British side—then fled to France because he feared to return to Ireland at that time. In Paris, he met Maud Gonne, whom he married, and they had a son, Seán.

The marriage was a tumultuous one and MacBride eventually returned to Ireland. At this point, he was impoverished and having trouble with alcohol until he secured a position with the Dublin Corporation. He was not a member of the Irish Volunteers or intimately involved with the leadership of the IRB, although he knew many of the players. In an iconic photograph, he can be viewed between Pearse and Clarke at the O’Donovan Rossa funeral oration at Glasnevin Cemetery in 1915.

John MacBride (Public Domain)

His involvement in the Rising, it seems, was serendipitous. According to his statement at his trial, he just kind of stumbled upon the revolution: “On the morning of Easter Monday I left my home at Glengeary with the intention of going to meet my brother who was coming to Dublin to get married. In waiting around town I went up as far as Stephen’s Green and there I saw a band of Irish Volunteers. I knew some of the members personally and the Commander [MacDonagh] told me that an Irish Republic was virtually proclaimed. As I knew my rather advanced opinions and although I had no previous connection with the Irish Volunteers I considered it my duty to join them. I knew there was no chance of success, and I never advised nor influenced any other person to join. I did not even know the positions they were about to take up. I marched with them to Jacob’s Factory. After being a few hours there I was appointed second in command and I felt it my duty to occupy that position. I could have escaped from Jacob’s Factory before the surrender had I so desired but I considered it a dishonorable thing to do. I do not say this with the idea of mitigating any penalty they may impose but in order [to] make clear my position in the matter.”

According to William T. Cosgrave, who succeeded Arthur Griffith as the President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State in 1922 and was the father of the future Taoiseach, Liam Cosgrave: “John MacBride told me…that his life-long prayer had been answered. He said three Hail Marys every day that he should not die until he had fought the British in Ireland.”

According to Father Augustine, who heard his confession and gave him communion, MacBride was “quiet and natural” and “knew no fear.” When they came to take him away he requested that he not be blindfolded or handcuffed, but these things were denied him. As he stood before the firing squad he said: “Fire away. I have been looking down the barrels of rifles all my life.” He died at 3:47 a.m.

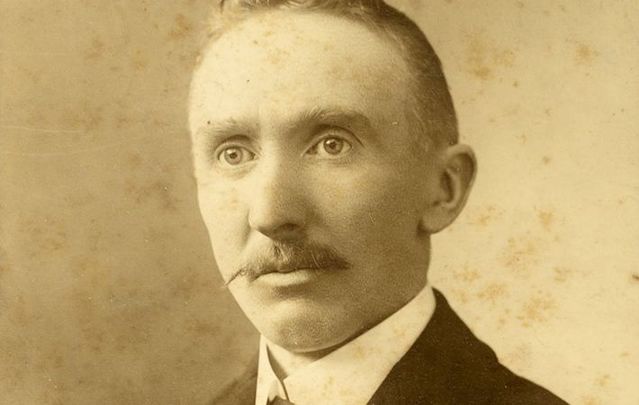

His estranged wife, Maud Gonne, when she heard the news of his death in Paris, said: “He made a fine heroic end which has atoned for all. It was a death he had always desired.”

Maud Gonne (Getty Images)

In Dublin, the Archpoet Yeats—who had unsuccessfully battled MacBride for Gonne’s affections—cast a more jaundiced eye on MacBride. However, by the end of the summer, he too had found some greatness in his erstwhile rival. In “Easter 1916," he wrote about MacBride:

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vain-glorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

There is one more footnote to the legacy of John MacBride. The son he had with Gonne, Seán MacBride, first followed in his father’s footsteps and was Chief-of-Staff of the IRA in the 1930s. After that, he turned politician, was elected TD, and as Minister for External Affairs in the John Costello coalition government which declared the Irish Republic in 1949. He went on to be a founding member of Amnesty International and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1974 for his work on behalf of human rights. And in what might have made both his lefty-leaning parents smile, he added the Lenin Peace Prize in 1975. He died in Dublin in 1988.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website and on Facebook.

* Originally published in May 2016. Updated in May 2025.

Comments