This is the story of three sisters - my grandmother and her two sisters - reared in Ireland in the late 1800s.

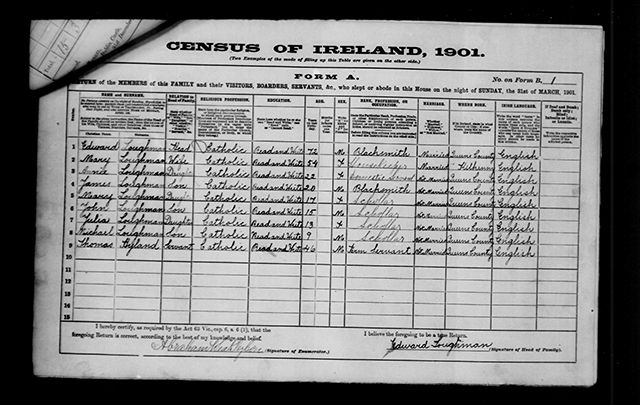

Their father, Edward Loughman, was 17 years old when famine ravaged Ireland. His brothers fled the country, emigrating to Massachusetts. Edward remained, rearing his five children in post-famine Ireland.

Cissie (christened Annie) was the eldest, James was next. Molly (christened Mary) was the middle child. John was fourth and the youngest, Julie, was my grandmother. (Michael died young)

We forget that the terrible Irish famine was not so very long ago. On the day my granny (b.1888) came to see my baby daughter (b.1977), she gazed in at the plump chubby child and said “Oh, isn’t she lovely and fat!” Her attitude to ‘fat’ was based on what she had heard as a child. Her own grandmother remembered people walking to the workhouse, dying on their feet. Her father remembered the coffin ships which took his older brothers to America. 40% of those on board had died from hunger and related diseases. The memory of the famine was still fresh in the mind of my grandmother. To be fat meant one would live.

The Loughmans lived in the center of Ireland in the county now known as Laois. In the 16th century, this small county was created from lands seized from the local Irish chiefs, the O'Moores, Fitzgeralds, O'Dempseys, and O'Dunnes. It was called Queen’s County.

The Loughmans were blacksmiths. They had a busy forge at their house, a craft greatly in demand before automobiles replaced horses. Forges were very sociable places. No one passed without calling in. Bills were posted there for auctions, road shows, and anything of note.

Cissie would cause a row in Heaven. As a young child, she demanded to be put sitting up on Lord Hamilton’s horse while it was being shod. Molly, Julie, and the boys stood by watching the iron being reddened in the fire, which was fanned by a bellows. The red-hot iron was removed by a long-armed tongs. Lifting the large hammer, their father moulded the iron into horseshoes.

The children listened to talk of Parnell, Daniel O’Connell, Gladstone, Home Rule, and The Land League. Julia, the youngest, loved hearing about the day local farmers unhitched the wedding carriage of Lord de Vesci and drew it into town. There was a dispute about shooting rights. When they played this game in their farmyard, Cissie always insisted on being the bride.

Julie loved reading in The Freeman’s Journal. She read about the famous Irish writer, Oscar Wilde. The paper also published the lyrics of Percy French’s songs, as well as poems by W.B. Yeats. Their mother was a great reader and shared her love of words with her girls.

Cissie, Molly, and Julie attended the endowed school in Grantstown, which was then under the patronage of Lord Castletown. Catholic, as well as Protestant children, attended this school. Cissie was very jealous, in 1897, when some of her Protestant classmates were taken to London to celebrate the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria - 50 years of ‘glorious reign’.

The three sisters received a wonderful education in this school, learning Latin, Greek, and Shakespeare. Other Irish children, at the time, did not have access to such schooling. The importance of education remained with them all their lives and, as a result, affected the lives of their offspring, including myself.

They farmed their land, too. The whole family was involved in cutting the turf, saving the hay, and helping with the thrashing. ‘The devil finds work for idle hands’ was a well-known fact!

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

The Loughman family went to Sunday Mass in their pony and trap. Mrs. Loughman wore a black beaded cape. Her hat always had a feather in it. Superstitions and religious beliefs were mixed up together. Some farmers’ wives tied holy medals and scapulars around cows’ horns so as they wouldn’t get brucellosis. The Banshee was feared by all.

For Molly, as a young child, the highlight of the year was The Ossory Agricultural Show, held in Rathdowney. Her father’s wild boar won first prize many times and her mother’s soda bread also won awards. Now, in 1899, Molly was hoping that the Aran jumper she had knit might win a prize there too.

The turn of the century was coming. Julie and Molly, aged 16 and 12, were content with their lot. However, Cissie was not. She had spent 19 years waiting for her life to begin. She now realized that, as long as she stayed at home, it never would.

She planned her escape carefully. One day, in 1901, when her father returned from the fair in Rathdowney, he did what he always did. He went into the parlor and placed the wad of notes into the drawer of the dresser. He then went across the yard to his forge. Cissie was ready. Her bag was packed. She slipped into the parlor, took all the money, and left. They never saw her again.

* Originally published in 2017, updated in April 2024.

Comments