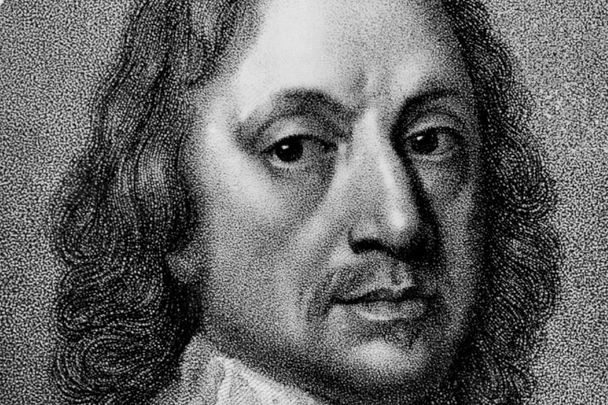

Oliver Cromwell, more than any other non-American figure from history, has enjoyed a rich and diverse afterlife in the United States.

From the country’s early days, colonial New Englanders shared his puritanism and were sympathetic to the republican experiment that he initiated in England after the beheading of Charles I in 1649; on the other hand, his rule also became an object lesson in tyranny, given his betrayal of the “good old cause” and his 1653 declaration as Lord Protector.

Conflicting views of the man resulted, often held by one person: Thomas Jefferson, for example, loathed Cromwell’s despotism and called his opponents “Oliverians,” but he also borrowed Cromwell’s saying that “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.” From the beginning, one could say that Cromwell was inscribed into the American project, though ambivalently.

These “memories” of Cromwell also bumped up against very different recollections held in Irish America. Especially for Irish Catholic immigrants through the 19th century, the memory remained strong of Cromwell invading Ireland in 1649, overseeing two spectacular massacres and a campaign of violent conquest, sanctioning forced transplantations to the west and deportations to Barbados, and above all enacting a policy of land confiscation that resulted in a new ownership regime. Many of the Irish in America viewed their present fates as bound up in the Cromwellian past, even if they subsequently recovered and then thrived in America. Remembrances could therefore be personal as well as more collectively shared.

When the highly prominent Carroll family first arrived in 1688, memory would have been strong of that family’s land being confiscated under Cromwell’s regime; though subsequent Carroll genealogies described the family as high-born and well-married in Ireland, they also recounted ‘Our Sufferings under Elizabeth & Cromwell.’ Even after settling in Maryland, the Carrolls could not escape various anti-Catholic and Cromwellian-associated ‘upstarts’ in their midst, who carried with them the old world stench of‘[t]ransplantations, sequestrations, acts of settlement, Explanations, Infamous Informations for Loyalty & other Evils forbid.’

Despite these earlier trials, however, the Carrolls would rise to become one of the most illustrious families in Maryland, with one descendent, Charles, signing the Declaration of Independence.

Cromwell was not simply invoked as a bad memory or figure of blame for a family’s dispossession, however. By the early 19th century, he was being recalled in order to bolster present-day debates or identities. The great Dublin-born and Philadelphia-residing printer Matthew Carey, for example, sought to raise the profile of his countrymen in works such as the "Vindiciae Hibernicae" (1819), which discredited the "unparalleled libels and calumnies" of English histories of Ireland.

Specifically, Carey addressed the falsehoods that pervaded accounts of the 1641 Catholic uprising against protestants, an event which was used in part to justify the “vengeance” of Cromwell on Ireland eight years later. For Carey, the rebels of 1641 were acting against tyranny, which implicitly linked them to the patriots of revolutionary America.

Accounts of 1641 were also exaggerated, Carey wrote, and hardly justified the worse atrocities committed by Cromwell, the "merciless wretch." "Never was the throne of the Living God more egregiously insulted," Carey added, as Cromwell in his dispatches and actions "made such a mockery of all the calls and duties of humanity and religion."

Carey was writing in part against the Orange movement then rising in America, and which repeatedly cited 1641 along with King Billy in its origin story. Other voices also joined his. An 1824 treatise "by an unbiased Irishman" entitled "Orangeism Exposed, with a Refutation of the Charges etc. Brought Against the Irish Nation," speculated as to why the Imperial Grand President of the Orange lodge in New York ‘chose to “forget” the period from 1641 to the invasion of William III, and especially “the infamy of their union with the puritanical, bloody tyrant, Cromwell.” This was all the more egregious, the writer added, since Cromwell’s crimes lived on through Orangemen today.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

By the mid-19th century, Cromwell only became more supercharged as a memory in England and Ireland, due in part to the myth-making of Thomas Carlyle and to a rising Irish and Catholic nationalism that found in Cromwell a charismatic figure who could function as a kind of shorthand for all English villainy in Ireland. These varying sentiments migrated in turn to America, thanks to the efforts of emissaries such as traveling lecturers, newspaper editors, or political activists. And indeed, Cromwell was an effective name to fundraise off, especially if his legacy in Ireland was to be overturned.

Most interesting perhaps was the form that memories of Cromwell assumed in the American Civil War, in a time of surging Irish immigration and war conscription. The abolitionist and martyr John Brown might have gladly fashioned himself as the “Cromwell of America,” but the Irish nationalist (and Ulster protestant) John Mitchel believed that the south should separate from the north as surely as Ireland should from Britain. Many in the south in fact viewed the northern incursion as akin to Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland, with William Tecumseh Sherman, for example, likened to Ironsides.

At the same time, Irish regiments in the Northern armies were said to have petitioned the medieval saint Lawrence O’Toole to deliver them from "English civilization,” “from British law and order,” “from the cloven hoof”—and “from the curse of Cromwell.” In this way, Irish soldiers in the civil war connected their current plight to a longer history, and one which was haunted in part by Cromwell.

Cromwell in this way was spread across a field of conflicting remembrances as different identities came into formation and asserted themselves in America. By the end of the century, he was the great ogre who also boosted Irish American nationalism, especially among Irish Catholic immigrants, providing the darkness against which the light of Ireland’s heroes—Hugh O’Neill, Daniel O’Connell—could be refracted.

By the same token, the Scots-Irish and a kind of “American Orangeism” also developed and began to claim Cromwell as part of their own identity and heritage, even though Cromwell had displayed no love for them, or for Presbyterians, in his time. These memories of Cromwell might have taken root in England, Scotland, and Ireland, but they arrived with immigrants and proceeded to scatter and take on hybrid forms in a new world whose conflicts served as an extension of the old. Transmitted through the generations and across a distinctly American and Irish American landscape, Cromwell’s name thus retained its menacing power, though whether that power will last is open to question.

*Sarah Covington is the author of "The Devil from over the Sea: Remembering and Forgetting Oliver Cromwell in Ireland."

* Originally published in Sept 2022, updated in April 2023.

Comments