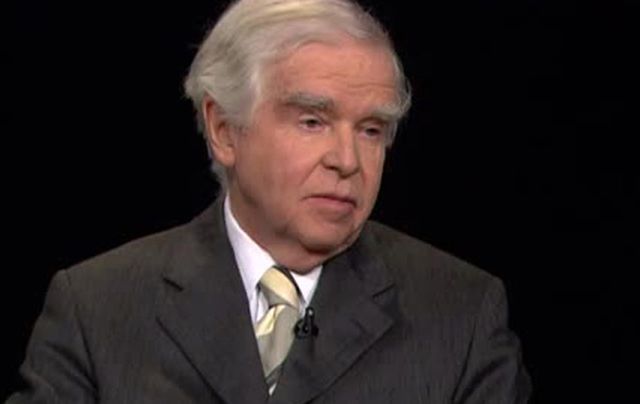

The AIDS crisis in the early 1980s was one that very few people wanted to even acknowledge, but Irish American New York physician Dr. Kevin Cahill thought otherwise. Here, he talks to Cahir O’Doherty in 2017 about a groundbreaking AIDS symposium he organized at the time, and why he decided to take the lead when no one else would.

Dr. Kevin Cahill’s patients have included Pope John Paul II and Ronald Reagan. The legendary American composer Leonard Bernstein was a patient and great friend. Irish poet John Montague slept in Cahill’s Fifth Avenue office during his brief New York visits, and the artist Louis le Brocquy was a friend and guest at his summer home.

But, like all true Irishmen, Cahill’s closest friends will testify, he draws little distinction between the head of the Catholic Church, the president of the United States of America or Lenny Bernstein’s ailing secretary (whom he made house calls to, astonishing her), and that is why his celebrated international career and his lifelong example are things to marvel at.

Born into a first-generation Irish American family in the Bronx, it was there that he learned – his late wife Kate liked to remind him – to speak a little too directly.

But that directness of manner stood to him, and to America in fact, when one of the most alarming health crises of the 20th century started presenting in the city’s hospitals, claiming the lives of lonely, terrified young men and mystifying health professionals in the early 1980s.

At the time Cahill, now 80, noted the slowness of the Reagan administration’s response to the gathering AIDS crisis and the general air of denial that accompanied its discussion.

Taking a lead on the matter himself, he organized the first major symposium on the crisis, attracting the most prominent names in AIDS research to a state of the art conference where the papers were quickly printed together in a groundbreaking book that was launched a month later by Senator Ted Kennedy on the Senate floor.

It is hard to overstate how important Cahill’s leadership was on the matter. But how he put those pieces together is a tale he hasn’t told publicly before, but one he has agreed to tell the Irish Voice now.

“I want to tell you the story of why the invocation by Terence Cardinal Cooke was so critical,” he says. “I never talked about this while he was alive for a lot of reasons, most of them professional.”

The participation of Cardinal Cooke in the symposium provided the political cover for Mayor Ed Koch, a friend of Cahill’s, to attend. In fact, the cardinal’s presence all but mandated it.

“I remember the symposium was on a Sunday and I think I made a house call with Cooke (who had health challenges of his own) on a Thursday and then on a Friday. He asked me how was my symposium going. I said, ‘Not very well because we’re not getting anybody attending,’” Cahill recalled.

“At that point I was the senior member of the Board of Health for the city so I knew Ed Koch fairly well and he would meet with us once a month.”

Cooke asked Cahill directly why he wasn’t getting people to participate and the doctor, a giant of the Irish American community, pulled no punches: “Because people like you are not speaking out,” he replied.

The directness worked. “My wife used to say to me my problem is I was born in the Bronx and so I say things very directly,” he says. (When Cahill speaks of his late wife Kate it’s with affection so palpable you can feel like you’re trespassing).

Cooke asked if it would help if he attended the event and Cahill said yes. “Well you write what you like me to say,” Cooke continued. So, Cahill went home and wrote up what he thought the cardinal should say at the opening of the groundbreaking conference.

“Then he wrote his own piece, which was far stronger,” says Cahill. “If you read it carefully he says they [the patients] are all our brothers and sisters and we must do something to help them.”

Cahill’s book, "The AIDS Epidemic," opens with a blessing from the cardinal and it ends with an era-defining medical call to arms from Congressman Ted (Theodore) Weiss, but it would not have existed if the cardinal had not taken the initial step to come on board.

“I could not get Congressman Weiss or anyone to attend, but once they heard that Cooke was attending everything changed. Ed Koch called up that afternoon and said he’d like to attend,” Cahill recalls.

Cahill has a photograph of that day on a wall at Lenox Hill Hospital on the Upper East Side. “If you look very carefully you’ll see Cardinal Cooke was quite ill at the time,” Cahill says. “We had him on high doses, but Ed Koch was there and so was Congressman Weiss.”

Cooke’s private health challenges may have inspired his compassion for fellow sufferers, but that kind of compassion was thin on the ground at the time if the truth is told.

In Congress, there was “very little sympathy or understanding” at the time for AIDS sufferers, Cahill says, with tactful understatement. “In fact, Bob Kaiser, a very dear friend of mine now deceased, was head of infectious diseases for the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and he told me of one particular visit he made to a southern senator.”

When told that the people being affected by AIDS were gays, drug addicts (and at the time, as it was thought, a special category that included Haitians) a senator, who was very senior in the public health service at the time, said, “Son, you aren’t describing a problem. You may have a solution.”

Cahill pauses, still shocked by the heartlessness, over three decades later. “That was a United States senator. That was what was going on in those years.”

In his hastily written speech at the symposium, Koch spoke of “AIDS victims” and New York City’s determination to “stop” the crisis, a political about-face for the mayor from his earlier refusal to even meet with gay leaders.

But rather uniquely for the time, Cahill remains conscious in his writings of the individual human lives behind the statistics. Even as the scale of the disaster was still unfolding he was thinking of the judgment of history and determining – correctly as it turned out – that the stories of “failure and neglect” would be surpassed by the remarkable “tales of heroism that illuminate this dark, lonely period of struggle to unravel the unknown…”

The other man who deserves great credit for his book was Ted Kennedy, Cahill says. Democrats were not in the majority at the time, so he couldn’t call a hearing. “But he told me if you can get good solid people, people who are presidents of the Blood Bank of America, for example, I can arrange for a book party and launch the book on the Senate floor.”

The symposium was in April 1983 and St. Martin’s Press published Cahill’s book in May, one month later, a remarkable achievement. It was the first and most significant medical pushback against the climate of hysteria and hostility.

“It was a very, very uphill battle just getting the medical community on board,” reflects Cahill.

Cahill's friend, the Irish poet John Montague, vividly recalls the atmosphere of the time in his memoir "The Pear Is Ripe."

Asking Montague to accompany him to meet some patients, Cahill explains that the young men they are about to meet are suffering “from a new malady that frightens people, a disease no one wants to deal with. Even the hospital staff are scared. They think of it as a kind of plague.”

Nurses, even some doctors, are so wary that they refuse to bathe these patients or dress their sores, Montague writes. So, they are very lonely as well as sick, ostracized as well as in pain.

“It wasn’t just bad or homophobic nurses banging trays onto tables in front of AIDS patients and then fleeing the room. They were all fearful for lives,” Cahill remembers.

In Ireland too, where he was chairman of the Department of Tropical Medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons, Cahill was asked to examine one of the earliest AIDS patients in Dublin.

“He was placed at the end of a long, empty hallway. Everyone was in masks and gowns because they were frightened. And the doctor walking me down to see this poor person said to me very quietly, ‘You know, he’s a Protestant.’”

That distancing tactic spoke for itself. It meant the patient was not one of us. It was a secret and, it must be said, an ineffective prayer to contain the disease’s reach.

“I remember giving a talk in Vancouver at the time [1983-‘84]. At the time, I had 46 cases of young men with rare infectious diseases and parasites related to AIDS,” Cahill recalls.

“I remember saying in the talk that it’s now been reported in 37 states of the United States and three countries overseas. How much more innocent can you get? We were at the very beginning of something we had no idea about.”

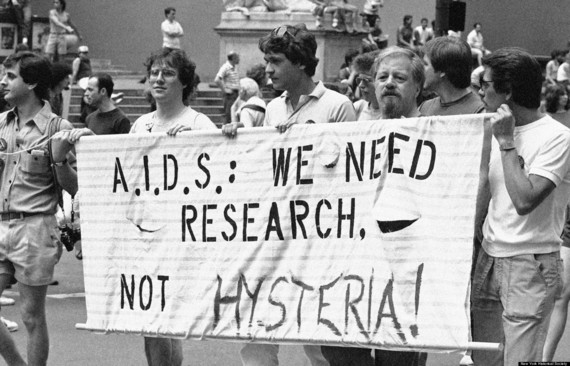

Marches call for medical research into AIDS and a stop to hysteria.

The scale of the AIDS crisis would affect every continent and eventually lead to the deaths of 36 million people, but in 1983, the American medical community was only beginning to discern the real profile of the looming disaster.

“As I say at the end of my own introductory chapter, you have to realize there’s more to admire in so many people. It’s not just a condemnation of the attitudes of the times. The crisis brought out the best in many people too.

“The only ones who could really stand up proudly at the end of that early period in the response to AIDS were the Gay Men’s Health Crisis Group and I put it right in the book.”

Records show the Reagan-era Press Secretary Larry Speakes scoffing at questions about the “gay plague” of AIDS. For him it’s even a subject for some levity: “I don’t have it. Do you?” he jokes.

“Franklin Delano Roosevelt had polio,” Cahill reflects. “It makes a very great difference if you had a leader who had sympathy for the people affected. If they see our worth or our value.”

But in life so much is determined by social status and at the time, gay men had little of that. “Probably true. You’d also have to say it was true for drug addicts,” Cahill says.

“You’d think the hemophiliacs might have brought something out; you might have had that press secretary say he was sorry for the little children who had been affected. I just remember nobody was saying anything. It was really more denial.”

Cahill’s Irish background and indeed his Catholicism were inspirational in his approach, his admirers would say, but so was the compassion that has marked his career.

When Louis le Brocquy, the Irish artist, was staying in Cahill’s backyard at the beach one July 4, he said, “Don’t you see the heart in the stars?” while looking at the American flag. Cahill said no, so Le Brocquy drew the thing out. Between the 50 white stars, he could trace hidden hearts.

“I take care of many, many people from overseas and they see America as a powerful nation. You know, we’ll crush you. America first. We’re going to get our way,” says Cahill. “But they don’t see the care and compassionate side which Louis saw in our flag.”

Le Brocquy created a piece to illustrate his idea, and that work now hangs in Cahill’s examining room, right above his examining table in fact. With his eye for detail and his appreciation of metaphor, it’s the best possible placement for the good doctor.

So many of the young men affected by the AIDS crisis were young people involved in the theater and the arts, Cahill recalls later in our interview. That awareness moved his great friend Leonard Bernstein who wanted to help support Cahill’s groundbreaking 1983 symposium.

“The whole event cost me $30,000. I had one patient who gave me the money for all the airfares. But then Lenny came to me and said he like to donate,” Cahill said.

“I said, ‘I don’t need any money it’s paid for.’ But Lenny insisted on giving a dinner for the medical participants that evening at the Dakota.”

Five years later Cahill was asked to review the historic book (the first published on the AIDS crisis anywhere) and he called everyone who had participated and asked them what they remembered most about it?

“Without exception, they answered dinner at Lenny Bernstein’s,” he laughed.

With that irresistible lure Cahill, a lover of art and poetry himself, changed history. People are alive today because he shouldered the responsibility of the physician and started the process that many of his contemporaries had eschewed. His contribution to the city and the country is simply inestimable.

To a generation of gay men, who have seen their fortunes change from a life on the margins in the 1980s, where they were often ostracized or ignored, to a new era of growing equality, Cahill is a hero of the first rank.

Not the kind of hero who loudly announces himself, but the kind who quietly changes minds and saves lives. He stood firm when others were running for the exit. His symposium and the book that followed it took an axe to the frozen sea of early 1980s political indifference, and after that progress started to become possible. He cannot be thanked enough.

*Originally published in 2017.

Read more

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments