For a country with a rich musical heritage and fascinating mythology, it seems only apt that Ireland’s national symbol is the harp.

Ireland is the only country with a musical instrument as its national symbol; how apt for a nation famed throughout the world for its music, culture, and dance. Intimately bound up with notions of Irish identity, it is found on official documents, the Irish passport, currency, and in every pint of Guinness and on Ryanair airplanes, two of the most instantly recognizable Irish brands.

The history and meaning associated with this instrument are fascinating, with origins in ancient lore, and most astounding of all, the fact that Irish harp music has been passed down through generations without sheet music being widely available. Traditionally learned by ear, this challenging but rewarding instrument has a touch of magic about it.

Listen to this Irish harp playlist as you continue to read:

The harp in mythology

The harp was said to have been invented by the Gaelic goddess Cana Cludhmor, the goddess of dreams, inspiration, and music. Legend has it that while walking on a beach one night, she was lulled to sleep by beautiful music. Upon wakin,g she realized the music had been created by the wind blowing through the sinews attached to a whale skeleton washed up on the shore, and this inspired the design of the harp.

Dagda, the god of fertility and agriculture, owned a magical harp made from oak and encrusted with jewels. He was the leader of the Tuatha Dé Danann, an ancient semi-divine race who ruled Ireland thousands of years ago. His harp summoned the seasons of the year when he played it. He brought it with him everywhere, and it flew into his hand when he summoned it. Those who heard him play were enchanted by one of three types of music he played—either to laugh with joy, cry with sorrow, or fall into a deep sleep. This remains the basis of three types of tunes for the harp: Goiltai (laments), Geantrai (celebrations), and Suantrai (lullabies).

A harp being played on the street at the 2013 Fleadh Ceoil.

Goiltai, Geantrai, and Suantrai were also the names of three sons born to Uaithne, a bard of Tuatha Dé Danann, and his wife, the goddess Boann, reflecting the music he played to her while she was giving birth. The three sons also became skilled harpers, each playing the type of music associated with their names, on elaborately decorated harps made of gold and silver.

The goddess Aibell was also renowned for owning a magical harp. She was a goddess of love, the untimely death of lovers, and prophecy, and her harp was a harbinger of death—anyone who heard her play would die soon afterward. Legend has it she visited the great warrior-king, Brian Boru, on the eve of his death at the Battle of Clontarf against the Vikings in 1014.

Brian Boru often played the harp during his lifetime, and it was long thought that the harp, commonly known as the Brian Boru Harp, on display in Trinity College had been his: legend has it that his son Donnchad presented it to the Pope when he traveled to Rome to seek absolution for murdering his brother in order to take the throne. It was supposedly then later given to Henry VIII as a gift in 1521. However, historians place its origins in the 14th or 15th century, with its carvings bearing similarities to the Queen Mary Harp from that period in the National Museum of Scotland.

The harp in Irish history

From the Medieval era through the 1800s, the harp was at the heart of Irish courtly life. Under the Brehon system, the harper was a central figure in the court of every Irish king or chieftain and afforded a special status.

In 1531, King Henry VIII of England declared himself King of Ireland and colonized the country. Although he recognized the central role of the harp in Irish life and culture and appointed it the official emblem of the realm, the harping tradition began to decline steadily after colonization. With the courts of the Irish High Kings and chieftains overturned, harpers lost their special status in society and had to become wandering musicians. Over the years, the harp became a symbol of resistance to the Crown and was eventually outlawed. In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I decreed that all Irish harpers should be hanged and harps burned.

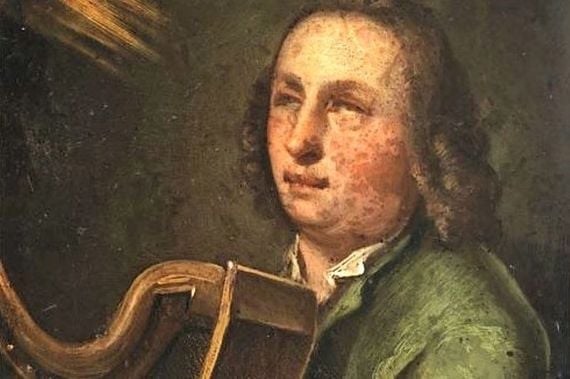

Somehow, the harping tradition survived. A harper named Turlough O’Carolan, who lived from 1670 to 1738, was one of the last of the era to compose any new music for harp. Most of his compositions were not written down or published in his lifetime—they survived in the repertoire of other musicians. Like many harpers of the day, O’Carolan was blind; it was thought to be due to diseases such as smallpox and measles being rife. O’Carolan is considered by many to be Ireland's national composer; the annual O’Carolan Harp Festival in Co. Roscommon commemorates his life and work.

Blind harpist and bard, Turlough O’Carolan.

The Belfast Harpers’ Meeting of 1792 attempted to keep the flagging tradition alive. Edward Bunting, a young organist, had been hired to transcribe all the music played, as Irish harp music is traditionally learned by ear rather than from sheet music. He continued this endeavor throughout his life, and the Bunting Collection is now infamous as a document of the traditional tunes. The Chieftains' 1993 album “The Celtic Harp”, which won a Grammy Award for 'Best Traditional Folk Album’, is a tribute to Bunting’s work.

In another effort to keep the harp tradition alive, an Irish Harp Society was established, and a harp school for blind boys was set up. In 1794, Padraig Dall O’Beirn (Patrick Byrne) was born in Monaghan, to a poor, Catholic, and Irish-speaking family; he went blind from smallpox aged just two. After attending the harp school, he went on to become one of the most feted musicians of his age, appointed Irish Harper to HRH Prince Albert in 1841, and was dubbed ‘the last of the great Irish harpers’. He was also the first Irish traditional musician to be photographed, while in Edinburgh in 1845. His death in 1863 marked the passing of the old style of playing. The Féile Patrick Byrne festival is usually held the week before Easter in Carrickmacross.

The harp today

The instrument itself has evolved, in build, size, and make-up, over the years. For almost a millennium, the harp had changed only organically, but in the 1800s, harp-maker John Egan brought about radical changes and innovations. The modern Irish harper (as opposed to a harpist, who plays a pedal or concert harp), plays in a different manner to their ancient forebears.

Traditionally, the strings of the old Irish harp were made from brass and plucked with the finger nails, the hand held as if closed around an imaginary ice-cream cone, producing a clear, sharp sound. The harp was played sitting against the left shoulder. The resonating chamber would have been carved from a single log of wood, usually willow, although Dagda’s harp was said to have been oak. Today, the harper plays with the harp to the right shoulder and strikes the strings with the pads of the fingers, thumbs up, fingers down.

Reviewing Mary Louise O’Donnell’s 2015 book, “Ireland’s Harp: The Shaping of Irish Identity”, Siobhán Armstrong, founder of the Historical Harp Society of Ireland, points out, “there is no single ‘Irish harp tradition’ but a more complicated overlap and juxtaposition of older and newer traditions,” taking into account the different styles of Irish harp which have evolved to the one generally accepted today.

The great harp robbery

The most famous harp existing in Ireland, the so-called Brian Boru Harp, on display in Trinity College Library, serves as the model for the insignia of the Irish State, as well as that famous Guinness logo. While its origins are debated, it is known that it was presented to Trinity College Dublin by William Conyngham in the late 18th century and was restored by experts at the British Museum in 1962. It was the subject of a dramatic robbery in 1969.

The Brian Boru Harp, at Trinity College.

Joseph Brady, an ex-British soldier, was recruited into the IRA in 1967 and came up with the idea of stealing the precious medieval manuscript of the Book of Kells and holding it for ransom. After breaking into the college and finding himself unable to access the Book of Kells, he took the harp instead and demanded a ransom of £20,000. A meeting point was arranged, and a dramatic sting operation ensued. The culprits were apprehended, and the harp, wrapped in black plastic, was recovered from a sand pit near Blessington in Co Wicklow.

* Originally published in 2022, updated in Dec 2025.

Comments