It's easy to sneer at the unionist and loyalist heavies who have been making threats about the Northern Ireland protocol that came into effect at the start of this year. They want it scrapped because they say the everyday experience shows that it is cutting off the North from the rest of the U.K.

*Editor's Note: This column first appeared in the February 17 edition of the Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

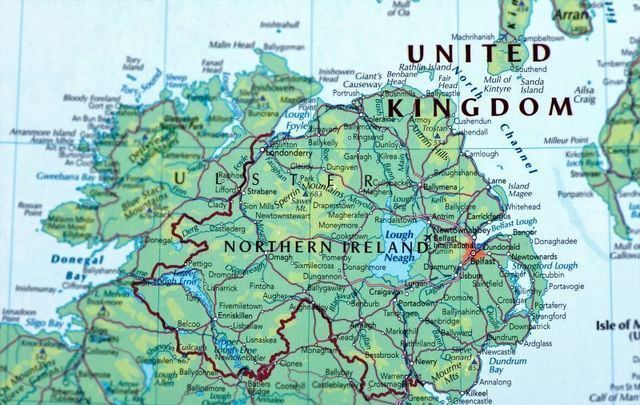

The protocol is the part of the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement that is designed to protect peace in Ireland by making a land border here unnecessary. Since Northern Ireland, like the rest of the U.K., is now out of the EU and the south of Ireland is still in, there has to be a border to protect the EU Single Market and Customs Union. But where?

The obvious answer is that it should be a land border between north and south. On the island of Ireland that is where the dividing line between being inside and outside the EU now runs. So that is where the border should be, just as there is a border everywhere else around the perimeter of the EU.

But it's not that simple. The general consensus in Ireland, the U.K., and the EU was that having a land border in Ireland could not be risked because it could become a target for Republicans and restart all the violence. The alternative eventually arrived at was the complicated arrangement that is the Northern Ireland protocol.

Under this arrangement, Northern Ireland has left the EU with the rest of the U.K. but it continues to apply Customs Union and Single Market rules in the North. This has meant there is no need for a land border in Ireland. But it means there has to be a border in the Irish Sea to check on goods coming into the North from the rest of the U.K. where the EU rules no longer apply.

This got the south off the hook. And initially, it did not seem to create too much angst in the North when the deal was done in October 2019. No one seemed to take it that seriously.

The Brexit transition year followed when nothing really changed and businesses carried on much as before instead of getting ready for what was coming. But that came to an abrupt end on January 1 this year when the transition period ended and the new protocol arrangements began to bite.

From that point on, there were major problems at the ports in the North as trucks bringing stuff in from the U.K. were expected to have a bewildering amount of paperwork and permissions in place before they could proceed. Businesses were caught up in red tape that meant days of delay. Shoppers noticed that items that used to come in from the U.K. to supermarkets in the North were missing from the shelves.

Suddenly, the reality of the protocol hit home and a lot of people in the North were very unhappy, especially the Unionists. If they were still part of the U.K. why was this happening?

The reaction in Dublin and to some extent in London was to say there was no alternative to the protocol. If there were delays and problems it was because businesses had not bothered to get ready. They needed to knuckle down and get to grips with the new requirements.

This was true to some degree. But it was also true that some exporters in the U.K. found it too much trouble and decided to stop supplying the Northern Ireland market rather than do all the paperwork.

From the unionist point of view, despite all the promises that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson had made, they were being treated differently. Those of a more extremist mindset saw it as the first step in cutting off the North from the rest of the U.K.

So within days, there was trouble. No Border in the Irish Sea, the graffiti on the walls near the ports read. Inspection staff trying to enforce the new rules at the ports felt under threat and stopped working.

All this provoked an irritated reaction among politicians in Dublin. The unionists were at it again, they said, even though the U.K. had signed up to the Withdrawal Agreement with the protocol in it.

Everyone needed to calm down and work through the difficulties. The protocol had to be accepted. The loyalist heavies could not be allowed to overturn it.

And that is all very well for us to say, but it ignored the very real problems the protocol was causing in the North. If the solution to the Brexit conundrum in Ireland had been a land border -- even an invisible, frictionless one -- would we have been so sanguine?

The loyalists saw that the threat of republican violence at a land border had stopped that, so why not make the same kind of threats at the ports to stop Northern Ireland being cut off from the U.K.? We can call them extremists and thugs, but from their perspective, it made perfect sense.

What was also a factor was the disastrous decision by the EU Commission three weeks ago to invoke an article in the Brexit deal which would close the Irish border, at least temporarily. This was done during the furious row between the EU and the U.K. over vaccine supplies and was designed to stop any EU vaccines being moved from the south of Ireland to the North and then on to the U.K.

This stupid decision was reversed almost immediately. But it had already done serious damage because suddenly it seemed the unthinkable -- closing the Irish border -- could be done if it suited the EU.

If that was the case, the unionists asked, why did the border have to be down the Irish Sea? Why was the North being cut off from the U.K. even though there was another solution -- a land border in Ireland -- that the EU was happy to implement when it suited them?

There is no easy answer to this mess. The situation is not helped by the half-hearted attitude of the British to the protocol.

Even though he signed up to it, Johnson has since said that he does not really think there should be a border in the Irish Sea. He says it interferes with the internal sovereignty of the U.K. (including the North) and therefore is unacceptable and will not work.

What the British want is for the protocol to be watered down to such an extent that it will barely function. Instead of all the paperwork, permissions, inspections of loads at ports, red tape, and so on, they want trade between the U.K. and Northern Ireland to be as free as it was before Brexit. They have told the EU they want the full implementation of the protocol and all the checks and documentation that entails to be put off until April 2023.

The other side of this is the EU attitude to Brexit and the desire not to let the U.K. away with anything. The absolute requirement for the EU is that the Customs Union and the Single Market must be protected, whatever the difficulties that creates in Ireland.

That means there has to be a border to control incoming trade into the EU. And that means documentation requirements and checks on all trucks and containers.

There is more than a suspicion in the North that the EU is deliberately making this as difficult as possible. It is probably more accurate to say that the EU is refusing to make any concessions.

The Single Market rules on standards required in all kinds of things from textiles to food and countless other products are very detailed and demanding. This is particularly the case in truckloads or shipments of live animals, animal products, foodstuffs, etc., where proof of origin and compliance with EU standards is required under the system of Export Health Certificates (EHCs).

This poses enormous difficulties, for example, for a truck bringing in a mixed load of different food products for a supermarket in the North, many of which will require an individual EHC. According to some businesses in the North, one truck may need dozens of these EHCs before they can come in.

What the British and businesses in the North want is a system where there is an assumption that all products coming in from the U.K. meet EU standards and therefore require minimal documentation. The EU, however, is conscious that after Brexit the U.K. is free to import from anywhere in the world, where lower standards apply, and some of these products may end up in Northern Ireland and from there be moved to the south and the rest of the EU.

So far there is little sign that either side is giving much ground. If anything, the claims and counter claims have been hyped up in the last few weeks. That is why last week Taoiseach Micheál Martin urged all sides to "dial down the rhetoric" and said he was concerned that Ireland could become "collateral damage" in the ongoing row.

So far no one knows how this can be resolved. Last weekend the senior U.K. minister Michael Gove was said to be considering a "mutual enforcement" plan under which the U.K. and EU would apply checks at the same level as each other. That would probably mean restoring the land border in Ireland.

If the British and the unionists continue picking holes in the protocol and refuse to implement it properly, that could mean that the border down the Irish Sea is no longer seen by the EU as enforceable and an adequate protection for the Single Market. The only alternative would be the return of the border in Ireland.

That is something the EU has always said is unthinkable. But after what they did during the vaccines dispute, can we believe them?

Comments