The book “Boss Tweed” by Kenneth D. Ackerman chronicled that he was no more corrupt than many of those prosecuting him.

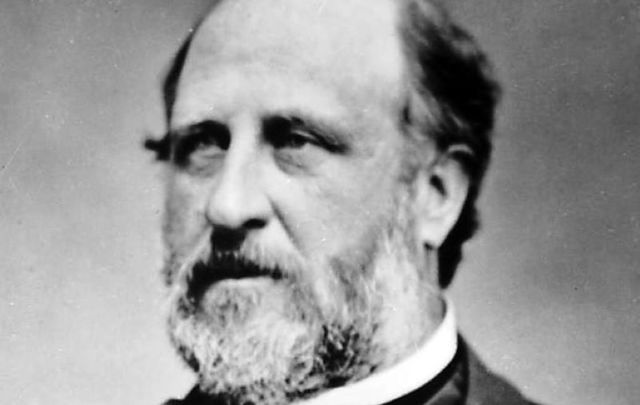

“Boss Tweed” by Kenneth D. Ackerman (Carroll & Graf Publishers) profiles the rise and fall of the most corrupt politician in New York history. It has been out for a number of years.

Despite his corruption, however, Tweed (1823-1878) was also a man ahead of his time who understood the power of the working man to effect huge political change.

Tweed also essentially created Tammany Hall, the greatest political machine in American history. The foot soldiers of Tammany Hall were the hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants who streamed into New York after the Famine desperate for work and shelter.

Unlike others who demonized the Irish, Tweed embraced them, giving them jobs and places to live.

In return for that, they voted en masse for Tammany candidates, thus providing Tweed with complete control over mayors, governors, and every other elected official in New York State. Using the Irish as levers, Tweed built the greatest political machine in history.

The Irish were the Mexican illegal immigrants of their day — only worse. The ruling class hated them because they were dirty, drunkards, and unruly, and they allowed interlopers like Tweed to gain power.

Tweed was incredibly corrupt, but probably no more so than the robber barons of his day who tried to corner gold markets on Wall Street, ran massive scams on railroad stock, and stole blind from everyone around them.

Tweed and his cohorts robbed everyone blind too, but in the process, they also created massive public work programs and created the infrastructure of New York City as we know it today.

Ackerman says that Tweed “conceived the soul of modern New York.” His mistake was to move far beyond the usual “honest graft” of some of his predecessors but to begin stealing too much at the time.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Yet he might have gotten away with it were it not for one Irishman named Jimmy O’Brien that he crossed, one newspaper, The New York Times, that was just emerging as a force, one anti-Irish cartoonist, the German-born Thomas Nast of Harpers Weekly, and the Orange riots that occurred when Catholic Irish tried to stop Orangemen marching down Eighth Avenue in triumph on July 12, 1871.

The Orange march in 1871 was originally banned by Tweed and his lackey, Mayor Oakey Hall, who feared violence on a massive scale because of tensions building up between the Irish groups. The Famine Irish were in no mood to tolerate the hated oppressors of the Orange Order marching through their neighborhood. Tweed understood that.

However, Governor John Hoffman, a Tweed nominee who saw himself as a future president but who needed to distance himself from Tweed to run, saw his opportunity to ingratiate himself with Tweed’s enemies.

He ordered the parade to go ahead, and on the day panicked troopers, who included Nast in their ranks, faced a huge Irish Catholic mob determined to stop their hated antagonists from marching. The troops fired into the crowd, and some counts put the fatalities at 130 including women and children.

After the smoke had cleared and the national outcry had commenced the powers that be decided that the Irish and Tammany were fully to blame and must be put in their place.

Louis Jennings, the English-born editor of The New York Times, decided that getting rid of Tweed and the hated Irish would be his life’s work, and he redoubled his efforts to do so.

Nast, for his part, turned his poison pen on Tweed and the Irish. His cartoons featured “horrific hordes of Irish brutes with torches, clubs, and pistols facing heroic guards and police,” as Ackerman writes.

“The Irish want more money and less work and fewer Protestants and cheaper whiskey,” wrote E.L. Godkin in The Nation, one of the leading publications of the time.

Amid the fury, The New York Times received the scoop of a lifetime. O’Brien, the former Irish-born sheriff of New York who had fallen out with Tweed over an unpaid bill, decided to part with incriminating documents that he had received. He sensed his opportunity after the Orange Day killings to bring Tweed down.

O’Brien’s documents came from inside the controller’s office, also run by an Irishman, Dick Connolly. The documents laid out chapter and verse the fake contracts, massive payoffs, and bogus sets of books that Tweed and his ring were maintaining.

The Times broke the story with their first-ever three-column headline under the title “The Secret Accounts.” The story was a sensation and made The New York Times, then just another New York newspaper, the leading paper of that day then and ever since.

Somewhere O’Brien, the original “Deep Throat,” was laughing. Tweed was doomed, and though he fought the charges he was eventually jailed and died in prison in April 1878.

His death brought to the end an incredible chapter in New York history. If you like New York history and the Irish role in it, you will love this book.

* Originally published in 2018. Updated in 2023.

Comments