A niece of Aidan McAnespie, whose murder produced a historic guilty verdict against a former British Grenadier after 34 years, has called upon incoming Taoiseach Leo Varadkar to charge Britain in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) if Westminster passes its pending amnesty legislation.

Una McCabe, McAnespie's niece, made the public appeal during a webinar broadcast hosted by the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) on Saturday, December 10, where she was joined by Fergus O’Dowd, chair of the Irish parliamentary Committee for the Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA), leading Belfast civil rights lawyer Niall Murphy, and Mark Thompson of Relatives for Justice.

McCabe also appealed to the Biden administration as British officials move ahead with their Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill, designed to take away legal rights to get criminal prosecutions, inquests, ombudsman reports, or civil suits in legacy killings.

You can watch back on the AOH webinar on the McAnespie verdict and Amnesty Bill, which was live-streamed on December 10, here:

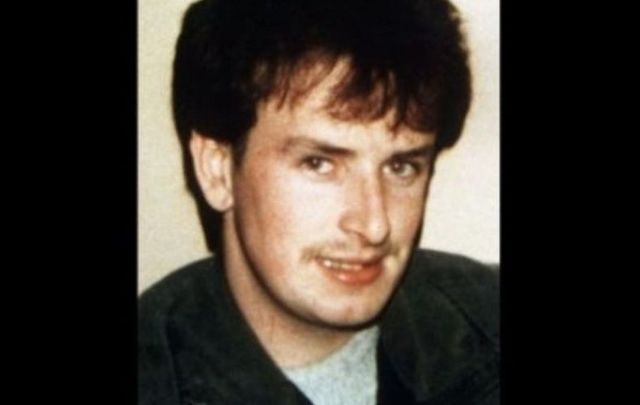

Aidan McAnespie was shot in the back by British Grenadier Michael Holden, firing a machine gun, on February 21, 1988. McAnespie, walking to the local Gaelic football grounds, had just been passed through the Auchnacloy British Army checkpoint, near the Monaghan border.

Holden claimed his “hand had slipped.” Trial Justice O’Hara called his claims “a deliberately false account of what happened” and found him guilty of manslaughter on November 25 of this year.

Holden became only the fourth British soldier convicted of killing Irish civilians during the entire period of The Troubles. No British soldier was convicted for the Bloody Sunday murders or the Ballymurphy Massacre. The McAnespie verdict also refuted claims by British officials that criminal prosecutions for Troubles killings were now impossible because of the passage of time.

McCabe said she wanted to speak for her mother, Eilish, and other family members who did not live to see the verdict, and was making a special appeal to the Irish government and America for hundreds of other families who have also been fighting for the truth about the murder of loved ones, but now fear British amnesty legislation.

Her uncle Aidan had to pass through the notorious Auchnacloy British Army checkpoint almost daily, either to work or play Gaelic football, and was repeatedly threatened. The family had tried to protect him by highlighting these threats to the press, political parties, and Catholic Church officials. A Sunday World Newspaper headline shortly before the murder described him as “Ireland’s most harassed man.”

McCabe was seven years old when her mother’s brother Aidan said goodbye to her and left to play Gaelic football. She remembered cars coming up the road and shouting for family members to come at once. As she was driven to the murder scene, her mother kept banging her fist on the dashboard and shouting “they got him…they got him.”

Because of the proximity to the Monaghan border, her family was able to get support from the Irish government which commissioned a special investigation and had the state pathologist perform a second autopsy. McCabe’s mother campaigned ceaselessly, became a founder member of Relatives for Justice, and spoke about the case in America, Downing Street, and Strasbourg.

McCabe said Aidan’s murder had not only robbed her of her uncle but also robbed her of her mom, who died from cancer at age 50. It is believed that Aidan’s murder played a major role in her mother’s death.

During the trial, she and other family members had to pass members of Northern Ireland Veterans holding banners and supporting the killer.

Following the guilty verdict, McCabe visited the graves of Aidan and of her mother and thought “they were finally at peace.” She said, “Peace with the past will only come from getting the truth through a fair and accountable judicial system.”

McCabe said she wanted this verdict to be a platform for all of the victims’ families still hoping for truth. She appealed to Varadkar and the Irish government to take a case to the European Court on behalf of all of these Irish victims.

She also said in September 1998, her mother had handed President Bill Clinton a letter with the names of hundreds of victims murdered by the British Army directly or in collusion with loyalists. Clinton had promised full support for justice and she hoped the Biden administration would keep that promise.

Read more

Niall Murphy, a leading civil rights lawyer on legacy cases, described the British amnesty bill as a “legal horror story” that “would close the courts to victims’ families.”

He said the Stormont House Agreement and European Court cases had set out mechanisms through which the British government said it would comply with European Law on the right to life. Instead, the British government will shut down inquests, ombudsman reports, civil lawsuits, and criminal prosecutions.

Families would fight the law but it would take at five years to go through the British courts before they could begin any case in the European Court. A case by the Irish government would go directly to the European Court and could get the amnesty law set aside in 8 months.

Fergus O’Dowd, a Fine Gael party member of the Dáil from Co Louth, chairs the Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement Committee (GFA Committee) which includes Irish Dáil and Seanad members, plus British Parliament MPs elected from the six counties. The GFA Committee has made this issue “an absolute priority” and fully supports Ireland taking a case to Europe.

O’Dowd, with approval from the full GFA Committee, made two formal written requests calling upon Attorney General Paul Gallagher to examine the British amnesty bill “with a view to taking an interstate case should you determine that the legislation contravenes the U.K.’s obligations under Articles 2 and 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights.”

The GFA Committee will ask the Irish foreign minister to appear before the committee in the New Year and will raise the issue directly.

Mark Thompson of Relatives for Justice described a meeting last week with Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney, attended by Maureen Rafferty, age 90, whose son was murdered 50 years ago. Mrs. Rafferty said that unless the Irish government takes a case to Europe, she did not expect to see any chance of justice.

Meanwhile, the British government continues to push ahead with the amnesty bill despite Irish opposition.

*This column first appeared in the December 14 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral. Fergus O'Dowd is brother to Niall O'Dowd, founder of the Irish Voice and IrishCentral.

Comments