A relaxed St. Patrick’s Day celebration in 1981, featuring an Irish American President who knew little about Ireland, proved to be a milestone in Anglo-Irish relations.

40 years before Joe Biden moved into the White House, Ronald Reagan received an invitation on the telephone to visit Ireland from the Taoiseach, Charles Haughey.

The phone call from Haughey was the first item on the agenda as soon as President Reagan arrived at the Irish embassy in Washington. Haughey’s invitation was an informal one, but Reagan’s officials at the event confirmed that he planned to visit Ireland at some stage.

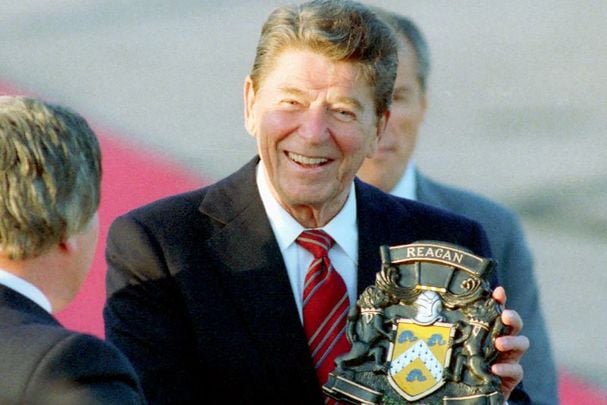

On his first St. Patrick’s Day as president, Reagan was delighted with the Irish government’s gift to him – a heraldic scroll charting his ancestry. Until that moment, Reagan said, he had never known about his Irish forebears in Co Tipperary because his father had been orphaned at the age of six. He was touched to know now precisely where his ancestors came from.

Reagan told his audience – including Senator Ted Kennedy and Speaker Tip O’Neill of the Friends of Ireland group – a joke his father used to tell about Irish Americans: the Irish built the prisons, and then filled them. This disturbed him until he realised that the Irish American policemen did the ‘filling.’ More seriously, the president quoted George Washington, who said that without the Irish contribution, the American Revolution and the revolutionary war could not have succeeded.

Haughey’s charm offensive at the embassy luncheon, with shamrock and an uilleann piper, had a very serious political purpose, of course, and the president visited Ireland on June 1-4, 1984, in advance of his re-election later that year.

Relations between the US and the Soviet Union, the world’s two superpowers during the Cold War, were tense during Reagan’s first term. Alarmed at the situation in Central America, his administration targeted the left-wing Sandinista regime in Nicaragua, and supplied the Nicaraguan counter-revolutionaries, the Contras, with money, training, and weapons. In turn, the Sandinistas backed rebels in neighbouring El Salvador.

Reagan’s visit to Ireland proved ‘difficult’ – according to the Taoiseach, Garret FitzGerald – owing to the unpopularity of his Central American policy. In Ireland, critics of US foreign policy were accused of being ‘anti-American’ and silent on Russian interference in Afghanistan and Poland.

In his address to parliamentarians in Dublin, the president made a significant gesture to the Soviet Union: he offered to negotiate a new agreement under which the two superpowers would pledge not to use force against each other.

When three deputies walked out of the Dáil chamber as Reagan began his speech, he alluded to one-party states in the Soviet bloc where ‘representatives would not have been able to speak as they have here’. More than 20 parliamentarians in total were absent for the speech, including two Labour Party senators who were later both elected president of Ireland: Mary Robinson, and Michael D. Higgins.

The protestors who took to the streets in Galway and Dublin during Reagan’s visit included many nuns and priests who identified with radical Catholic clergy in Nicaragua and El Salvador. 33 women, participating in a nuclear disarmament protest opposite the American ambassador’s residence, were arrested.

The president, in his address, referred to the Northern Troubles, and reiterated his position that he would not ‘interfere’ in Irish matters. But he again offered his support to British-Irish efforts to find a solution to the crisis in the North. Some months later, Reagan played a crucial part in kickstarting the political process that brought an end to the armed conflict in the North.

Up to this point, the US refused to use its ‘special relationship’ with Britain, its key Cold War ally, to influence Britain’s approach to the Northern Ireland crisis. Reagan and the British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, enjoyed a particularly close political relationship.

Thatcher narrowly escaped assassination in October 1984 when the IRA bombed her hotel during her party’s annual conference. Following the bombing, Reagan departed from the White House’s longstanding non-interventionist position on the Irish question and urged Thatcher to intensify Anglo-Irish dialogue.

The Irish lobby in Washington had leverage with the president in the House of Representatives, in the shape of Tip O’Neill, in turn influenced by Ireland’s leading constitutional nationalist, John Hume. O’Neill urged Reagan to persuade Thatcher to listen to Irish proposals for a new approach to the Troubles. These negotiations concluded with the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, the first step in a long-running diplomatic engagement that resulted in bringing political violence in the North to an end.

Ronald Reagan promised that he would be a friend to Ireland when he began his presidency in 1981 – by the end of his first term in office, he delivered on that promise.

*John Mulqueen is the author of "An Alien Ideology: Cold War Perceptions of the Irish Republican Left" (Liverpool University Press, paperback, 2022).

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments