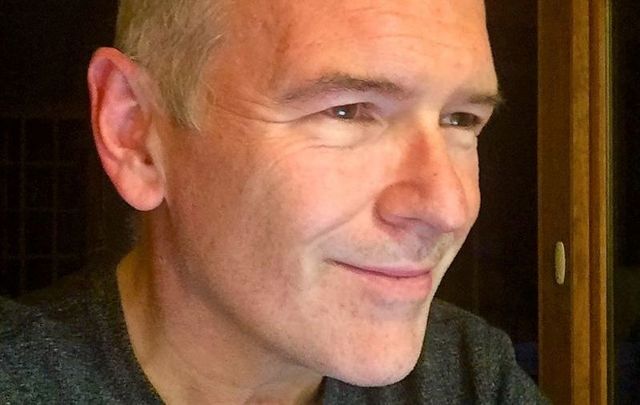

It was fitting that in his last column for The New York Times on May 26th, Jim Dwyer wrote about the quiet heroism of his great grandmother in saving her family during the 1918 flu pandemic.

She was known as Nan the Point from a remote area near Killorglin in Co Kerry. Her daughter Mary, her son in law Paddy, and seven children had all contracted the Spanish flu and were helpless in its wake huddled cold and sick in a small cottage.

Every day, the elderly Nan the Point, who had somehow come through unscathed, would tramp up the mountainside with a pot full of potatoes and vegetables for her daughter’s starving family.

Somehow they survived, and the Dwyer children who were saved scattered years later access the globe. One ended up in New York, and Jim Dwyer was his grandson.

He made the point in unique Dwyer fashion that without Nan the Point and the unsung heroes of the pandemic we battle today, fresh generations would never survive.

It was a typical Dwyer column, beautifully written and imagined and imparting a lesson about forgotten heroes of yesteryear whose imprint survived and today’s heroes like poorly paid immigrant cleaning ladies, cooks, and aides who have helped save so many lives.

Dwyer had an incredible empathy and insight into the lives of those who struggled in life. I accompanied him on a few of his interviews and learned quickly why he was such a master of prose. No detail was too little, no angle uncovered. The finished product was like a well-polished gem, impossible to match.

Dwyer was a member of the Mick Clique, a group of incredibly talented column writers like Jimmy Breslin, Pete Hamill, Mike McAlary, Dan Barry, and Dwyer who transformed and changed New York with their writing.

Dwyer turned prose into poetry no matter the context. He rode the rails every day of the New York subway and covered every imaginable occurrence. He witnessed a snake on the train, a ritual chicken sacrifice, but it wasn't just the bizarre events, he tracked the life stories of those who rode the rails giving us a clue into the hidden lives of millions of subway riders.

He never forgot the little people, indeed he celebrated them, spoke truth to power about them. Little wonder Rudy Giuliani hated him. Jim was far too righteous to let the Mussolini leanings of Giuliani go unnoticed. He was among the first to point out the Central Park Five, young Black men falsely accused of raping and badly beating a white jogger, were innocent. Donald Trump wanted them executed.

On 9/11, he conducted an interview with an occupant of the Twin Towers even as the man faced certain death as the fire flickered towards him. His book “102 Minutes” chronicled events of that day, what mistakes were made, what heroic deeds were done better than any other publication.

He had written a book about the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center and immediately made the connection as to who the bombers were.

He covered the US invasion of Iraq as only Jim could, accompanying the US Army there and relaying the daily struggles and lives of the soldiers on the ground and ignoring the generals.

Jim also put the case of Rory Staunton, my 12-year-old nephew who died of Sepsis in 2012 after dreadful hospital care, on the front page of The New York Times and sparked a movement to make parents worldwide more aware of the disease.

He was beloved as Senator Chuck Schumer noted:“I am deeply saddened to hear of the passing of a great New Yorker and proud Irish American, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jim Dwyer. His loss leaves a gaping hole in the New York media landscape and in our hearts."

When we started Irish America Magazine and the Irish Voice newspaper (sister publication to IrishCentral), he was incredibly generous with his time and advice. He wrote a column about our endeavors that makes me laugh to this day, describing our first office upstairs from a Turkish carpet company staffed by Turks with a Jewish business on the same floor. It was an amalgam of New York that only Dwyer could summon up and it made great reading.

We went to Northern Ireland together and I was able to tip him off when the 1994 IRA ceasefire was going to be announced, and I'm happy to say that helped him win a Pulitzer as his Irish columns were cited.

He had originally planned to be a doctor, but a spell with the Fordham University student publication changed his mind. Medicine's loss was writing's gain.

These last few months as he bravely battled his illness he was the same upbeat Jim in his texts and emails. He was a gentleman to the tip of his toes, one of the most profound insightful, funny, endearing people I have met in my lifetime.

His parents were from Kerry and Galway, my deepest sympathy to wonderful wife Cathy, and kids Kathleen and Moira.

He is with Nan the Point now, and no doubt he’s squeezing out the finest detail of how she saved his family. The truth mattered to Jim Dwyer and he lived it. He is irreplaceable. In his own words in his last column he said:

“I am one of the 45 great-grandchildren who came from the house that did not die out because Nan the Point left pots of food on a rock, upwind.”

The world was a much better place that his family survived.

Comments