Brendan Behan was larger than life—a literary powerhouse, a raconteur, and a man who lived (and drank) with reckless abandon. Born in Dublin on February 9, 1923, he left an indelible mark on Irish literature with works like "Borstal Boy" and "The Quare Fellow". His untamed genius, sharp humor, and tragic struggles made him one of Ireland’s most unforgettable figures. On this day in 1964, at just 41 years old, Behan died in Dublin’s Meath Hospital, leaving behind a legacy of brilliant writing and unforgettable wit. Here’s a look back at the man, the myth, and the madness of Brendan Behan.

At just 41 years old, Behan died at the Meath Hospital in Dublin of complications from diabetes and alcohol.

Allegedly, his last words to the nun attending him were: “Sister, may all your sons be bishops.” Apocryphal or not, that story, unjustly, sums up the life of Behan, a writer slaughtered by drink.

To put it mildly, Behan and drink did not mesh. And he seemed to know it. “One drink is too many for me,” he once said, “and a thousand not enough.”

Behan was born into the slums of Northside Dublin on Russell Street—although it should be pointed out that the tenement he grew up in was owned by his granny.

To understand Behan the writer, I think one must understand his virulent Republican background. His mother Kathleen’s brother, Peadar Kearney, wrote the Irish national anthem, “Amhrán na bhFiann,” (“The Soldiers’ Song”) and his father was in the IRA, most prominently helping to burn down the Custom House in Dublin in 1921. While his father was imprisoned, his mother went to see Michael Collins in search of money. She always called Collins her “Laughing boy.” Behan remembered that and at the age of 13 penned the sweet and gentle poem, “The Laughing Boy,” about Collins’ death:

’Twas on an August morning, all in the dawning hours,

I went to take the warming air, all in the Mouth of Flowers,

And there I saw a maiden, and mournful was her cry,

“Ah what will mend my broken heart, I’ve lost my Laughing Boy.”

Behan Tracks Down Beckett in Paris

In 1939, at the age of 16 and a member of the IRA, he tried to drop a bomb down the smokestack of a British man o’ war and found himself locked up in a British borstal for his trouble. His experiences there would lead to his greatest work, "Borstal Boy," a memoir.

After prison in both England and Ireland for his IRA activities, while trying to write (“I am a drinker with writing problems”), Behan got away from the temptations of Dublin and went to Paris, like two other famous exiled Irish writers: James Joyce and Samuel Beckett. Beckett had just become known as the author of "Waiting for Godot" and Behan, relentlessly, went in search of him.

Behan read a piece on Beckett in Merlin magazine by an American by the name of Richard Seaver. Of course, he figured the best way to meet Beckett was by accosting the unassuming Seaver. In one of the great descriptions of the color, profanity, and genius of Behan’s speech, Seaver recalls in his memoir, "The Tender Hour of Twilight," the first thing Behan said to him: “I missed Joyce,” Behan began. “I hated that fucking Yeats. Flann O’Brien leaves me cold. He’s so fucking Irish. The same goes for John Millington Synge, who stuck his fucking ear to the fucking wall to overhear how the peasants really talk, then put it into his fucking plays as though he’d made it up himself! Damned thief! Anyway, from what you wrote about Beckett, he sounds like the real thing. So tell me how to find him.” Behan—a “cute ‘hoor” as they like to say in Dublin—said of Beckett: “He’ll receive me the same way Joyce received him.”

A wary Seaver—who would be instrumental with Barney Rosset in bringing Beckett’s work to American readers—tried to put Behan off, but Brendan was persistent. Seaver left messages to warn Beckett, but the relentless Behan tracked him down anyway—at six o’clock in the morning! He occupied Beckett for three hours until Beckett had to leave for a rehearsal for "Waiting for Godot."

“Samuel Beckett,” wrote Ulick O’Connor in his biography 'Brendan Behan,' “also met him at this time and was pleasant to him in a slightly sad, sardonic Dublin accent. Beckett, like Joyce, was always pleased to meet Dubliners in exile…”

Beckett himself confided to Seaver: “Poor lad, at the rate he’s drinking, he won’t last another decade.” Beckett was right.

A Writer Who Can’t Write

But his writing was always to be infected by his desire to drink. His three greatest works were written before liquor grabbed him by the knees. "Borstal Boy" is a superb book, full of insights, howls, and absolutely beautiful writing. His two plays, "The Quare Fellow," about a man—the “quare” fellow himself—about to be hanged, and "The Hostage," about a British soldier held by the IRA as a prisoner, are also superior works.

"The Quare Fellow" was made into a movie in 1962, starring the American actor Patrick McGoohan. Many of the scenes were filmed inside Kilmainham Gaol.

"The Quare Fellow" also contains one of the most beautiful songs—written by Behan himself, “The Auld Triangle,” about the lonely life of an inmate in Mountjoy Gaol.

Listen to Behan sing it here:

It was also in this period of (relative) sobriety that Behan wrote the beautiful short story called “The Confirmation Suit,” which will leave the reader howling.

But after he became famous with plays running on Broadway and the West End of London, the narcotic of celebrity betrayed him. He would appear on television drunk and people would laugh. But the addiction of attention boosted his need for attention—and more drink. By the early 1960s, he was hanging around New York, living at the Chelsea Hotel on West 23rd Street, loitering at the YMCA across the street looking for fodder to quench his hidden homosexuality (revealed by O’Connor in his biography), getting drunk and, of course, not writing anything.

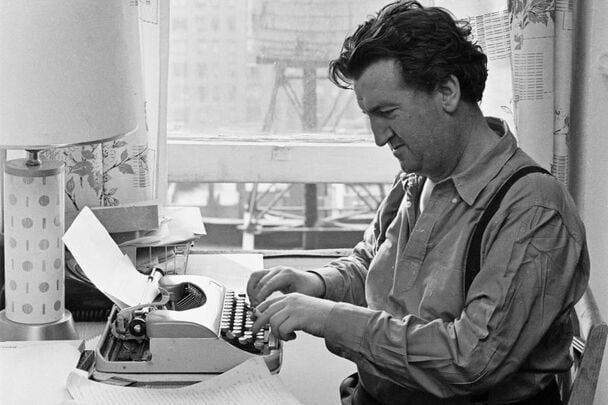

His British editor at that time, Rae Jeffs, traveled to New York to push Behan back to his typewriter (finely recorded in her book, "Brendan Behan: Man and Showman"). That proved impossible, so she started recording him. His last three books, "Brendan Behan’s Island" (1962), "Brendan Behan’s New York" (1964), and "Confessions of an Irish Rebel" (1965)—all spoken into a tape recorder—are by no means bad books, but one can see that they are to a great extent “cut-and-paste” jobs.

The Legend Lives On

At his death, he left a wife and an infant daughter. Usually, characters of Behan’s type, in time, fade, remembered only as a quirk of the time. But Behan has remained in the popular imagination and culture. Immediately after his death “Lament for Brendan Behan,” a beautiful ballad, was written by Fred Geis. Listen to Liam Clancy singing it here:

In the 1970s, Dublin-born actor Shay Duffin did his one-man show “Brendan Behan: Confessions of an Irish Rebel,” which won the Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award in 1975.

Larry Kirwan, the long-time leader of the Black 47 rock band, is currently working on his own Behan project. “I always intended writing a musical about Brendan,” Kirwan told IrishCentral, “basically because the man himself was so musically oriented. I don’t think you can really capture him without song. I could also instantly hear in my head the type of music that would summon his essence. His alcoholism was the put-off. It touched too close to home for a working musician and is ultimately really depressing. About six months ago, I figured out how to excavate the real man from inside the alcoholic bubble and the ideas have flowed since.

“He’s a very important figure in the Irish Punk/Rock scene,” Kirwan continued. “Shane MacGowan, although an original, adopted much of Brendan’s trappings. The Tossers have a great song, 'Brendan O’Beachain;' Black 47 has 'The Ballad of Brendan Behan.'"

We get him and his lonely genius, because we’ve all been down part of his path, yet managed to get out alive. Brendan’s the man!

“Brendan was one of us,” opined Kirwan. “He said what he liked and did what he pleased. He was political, generous to a fault, and deadly afraid of slipping back into anonymity. Fame killed him. He drank too much and became a boor. But, oh, what a writer. Even re-reading 'Borstal Boy,' you still get the feeling that you missed out on so much. His plays broke new ground and, with the right reimagining, can be relevant all over again. There’s so much overlooked in Brendan’s life and work. No matter, he’ll always be ‘our Brendan.’ ”

The Quotable Behan

Behan, of course, was never at a loss for words. He knew the Irish and he knew his audience, whatever their nationality, well. My two favorite quotes from Behan are:

“If it was raining soup, the Irish would go out with forks.”

His definition of the Anglo-Irish: “A Protestant on a horse.”

Here are some of his most memorable quotes:

“Other people have a nationality. The Irish and the Jews have a psychosis.”—From "Richard’s Cork Leg"

“It’s not that the Irish are cynical. It’s simply that they have a wonderful lack of respect for everything and everybody.”

“When I came back to Dublin I was court-martialed [by the IRA] in my absence and sentenced to death in my absence, so I said they could shoot me in my absence.”

“The big difference between sex for money and sex for free is that sex for money usually costs a lot less.”

“The most important things to do in the world are to get something to eat, something to drink and somebody to love you.”

“Critics are like eunuchs in a harem; they know how it’s done, they’ve seen it done every day, but they’re unable to do it themselves.”

“An author’s first duty is to let down his country.”

“There is no such thing as bad publicity—except your own obituary.”

Of course, Brendan is most often remembered today with a smile. Years ago, there was a joke about an Irish homeless man begging on the streets of London. This very proper Englishman, with impeccable Saville Row suit, bowler hat and umbrella stops in front of him and is disgusted. “Neither a borrower nor a lender be,” he declares, “William Shakespeare.”

“F--- you,” said the Irish beggar. “Brendan Behan.”

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," now available in paperback from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook.

*Originally published February 2017. Updated in March 2025.

Comments