The ironic tale of a Confederate Irish soldier who fought at Gettysburg and is the sculptor of the Irish Brigade Monument to New York regiments close to the American Civil War battlefield.

It is a remarkable irony of history that the most visited monument at Gettysburg, that of the monument to the New York regiments of the Irish Brigade, located on Sickles Avenue, was sculptured by a Confederate soldier who fought at Gettysburg.

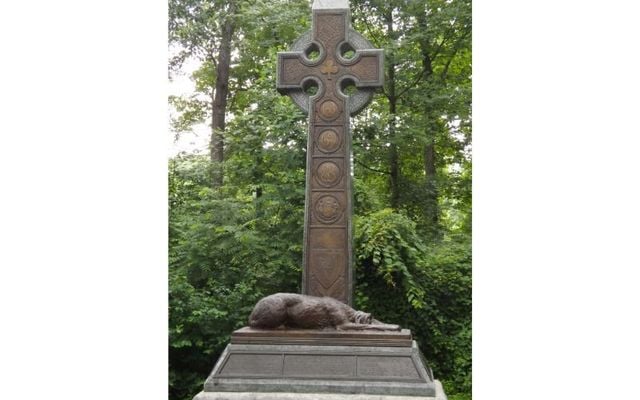

The monument, dedicated in 1888 and located near where the Irish Brigade fought, is adorned with the traditional Celtic cross on top of a shaft of polished granite commemorating the three New York regiments of the brigade, the 63rd, 69th and 88th New York Volunteer Infantry regiments. At the base of the monument an Irish wolfhound, the Irish symbol of loyalty, honor and fidelity, is depicted weeping for his fallen master.

The sculptor of the monument was William Rudolph O’Donovan, a Confederate soldier of Irish descent, who himself fought in the Battle of Gettysburg.

O’Donovan was born in 1844 and spent his childhood years in Preston County, West Virginia, east of Morgantown, which was then part of the state of Virginia. When he was a young boy, his family moved to Carmichaels, Pennsylvania, just east of Uniontown, where he was apprenticed to a marble cutter. Soon after, he left his family to seek work near where he spent his early years in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

In 1861, at the age of 17, O’Donovan enlisted in the Confederate Army, serving with the army of Northern Virginia throughout the American Civil War with the Staunton Virginia Artillery before the surrender of General Lee, at Appomattox.

O’Donovan was wounded at the Battle of Malvern Hill, Virginia, on July 1, 1862, during the Seven Days of the Union Peninsula Campaign. The Irish Brigade was heavily engaged in this battle.

One year later on July 1, 1863, in the first days fighting at Gettysburg, O’Donovan would be manning one of the four Napoleon guns of Captain Asher Garber’s Battery, near present-day Jones Avenue, northeast of Gettysburg. This was part H.P. Jones Battalion of General Jubal Early’s Division and General Ewell’s Corps. His battery was engaged in destructive firing at Union troops who were retreating east from Seminary Ridge. Garber’s Battery would be held in reserve for the final two days of the battle.

After the war, this self-taught artist went to New York City to seek a career in the arts. He found work in the National Fine Arts Foundry, owned by Maurice Power, that made three-dimensional figures and bas-relief tablets later cast in bronze.

Power was the contractor who furnished American Revolution and Civil War sculptural monuments to Civic Commissions to memorialize historical events and mark hallowed sites. American architect John H. Duncan who also worked with Power’s Fine Arts Foundry was the designer of the Celtic cross monument at Gettysburg.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

One Irish Brigade veteran wrote of O’Donovan:

“It is not generally known that he is an ex-rebel, but so it was, and so often opposed to the Second Corps in which the Irish Brigade served from the first, that his election of the old Celtic emblem (the Celtic Cross) was intended as a compliment, and his selection as the artist for the monument was a remarkable coincidence.”

O’Donovan would work for the foundry until close to the end of the century. Some of his other famous works include a statute of Archbishop John Hughes at Fordham University, the statute of George Washington at the Trenton, N.J. Battlefield and a Confederate Memorial Monument in Wilmington, North Carolina. He died in New York City in 1920, aged 76.

It should be noted, that at the base of the Celtic Cross monument, O’Donovan sculptured bas-relief bronze depictions of artillery soldiers loading and preparing to fire their cannon, something O’Donovan himself was part of on the Confederate side with his unit the Staunton, Virginia Artillery Battalion. These depictions were in tribute to James Rorty’s 14th Independent New York Artillery Battery, which was a part of the Irish Brigade, but was detached at Gettysburg and assigned to the 1st New York. Light Artillery.

Comments