Award-winning Irish poet John Montague wrote in his memoir "The Pear is Ripe" about the dreadful toll the new and strange disease called AIDS was taking in 1982. He profiled an Irish American doctor, Kevin Cahill, heroically leading the fight to humanize the patients.

Editor's Note: October marks AIDS Awareness Month, an opportunity for people worldwide to unite in the fight against HIV, to show support for people living with HIV, and to commemorate those who have died from an AIDS-related illness. Today we mark AIDS Awareness Month with this profile of Dr. Kevin Cahill's work with AIDS victims in New York.

1982: I am in New York to give a few readings, and after I have discharged my literary duties I would like to drop into exhibitions, trawl bookshops, and see friends. Only I have just a few days to spare from my teaching obligations in Cork, so I must speed round the city. Also, I am short of what my hippie friends call “bread.” Since time is of the essence, I would like to stay in a place where I would not be burdened with social obligations, but a hotel would swallow my fees. What can I do?

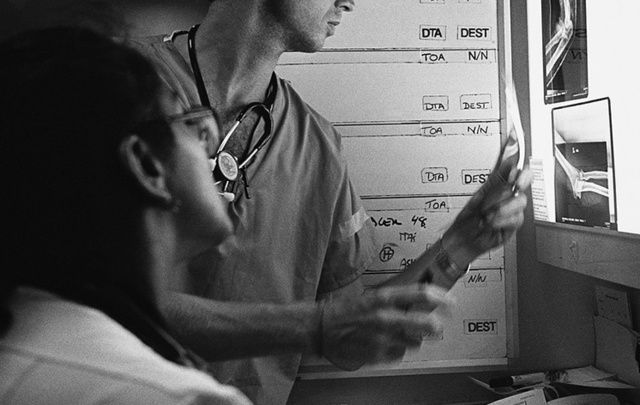

A doctor friend, Kevin Cahill, whom I admire a great deal offers to put me up in a spare bed in his temporarily empty clinic at an uptown hospital. I admire him because he is a new kind of doctor, aware not only of local but also of international health problems, seeing the wider picture of man struggling in our new world, where prosperity and poverty collide. He also loves art in its many forms, especially contemporary Irish painting and sculpture.

After a busy but happy week tearing through New York, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the galleries of SoHo, from the cluttered flats of literary pals to the tidy Queens home of my Aunty Eileen, I say goodbye to my doctor friend. I ask what could I possibly do for him, to express my thanks for his eccentric form of hospitality.

He seems to reflect for a minute, and then surprises me by suggesting, “Perhaps you could come with me to speak to some patients?”

As I am puzzled, not being a doctor, he explains further “But these are special patients, suffering from a new malady that frightens people, a disease no one wants to deal with. Even the hospital staff are scared. They think of it as a kind of plague.”

I am once fascinated and frightened, but he tells me that it is not contagious in the ordinary way, though the symptoms are extreme that people do not know how to react. Nurses, even some doctors, are so wary that they refuse to bathe these patients or dress their sores. So they are very lonely as well as sick, ostracized as well as in pain. Compassion wins the day and I find myself in a white doctor’s coat, heading for the ward where these strange people (curiously, all men) are corralled. “Remember, all you have to do is speak to them, and perhaps shake their hands,” my doctor friend has advised.

Read more

“This is Doctor Montague, a distinguished physician from Cork” he announces (the doctor bit a literally true, though not the medical sense), as we walk along a line of beds. Yes, they are all men, but damaged men, some mottled with purple sores, one going blind, all fatalistically silent, stricken. We pass along the beds one by one, and engage the men in conversations, for which they are heart-breakingly grateful, smiling and gazing eagerly at us out of their exhausted eyes. I am introduced to a gaunt man who tells me he is writing a play: I say that I have seen an Edward Albee revival, and intend to see a Eugene O’Neill that evening.

He discusses both playwrights and both plays, a sensitive and intelligent man whose face I seem to see through a slowly closing door.

An hour passes, during which some of the men even relax at our fairly normal badinage, probably relieved to be treated as ordinary human beings, albeit human beings in great pain.

Then a clatter, as the nurses burst in, trundling the evening meal on noisy trolleys. They do not put the trays down gently, but thrust them, nearly bounce them, onto the patient's’ tables. And they do not smooth the pillows or straighten the bedclothes in the usual caring manner of nurses, but rush in and out without a word or even a smile, like bats out of hell.

* Adapted from the late poet John Montague’s book “The Pear is RIpe” published by Liberties Press.

Comments