The amazing tale of how "My Fair Lady's" George Bernard Shaw and "Sherlock Holmes'" Arthur Conan Doyle fought to save Casement from the hangman’s noose.

On August 3, 1916, the British executed Sir Roger Casement by rope for his part in the Easter Rising. He would be the last of the sixteen rebels executed by the British and the only one murdered outside of Ireland.

In the weeks leading up to this final chapter of the Easter Rebellion, many in Ireland and England sought to stop Casement’s trip to the gallows.

Two of them were literary giants with connections to Ireland—George Bernard Shaw, creator of "Pygmalion" (later turned into "My Fair Lady"), and Arthur Conan Doyle, the inventor of the most famous detective of all time, "Sherlock Holmes".

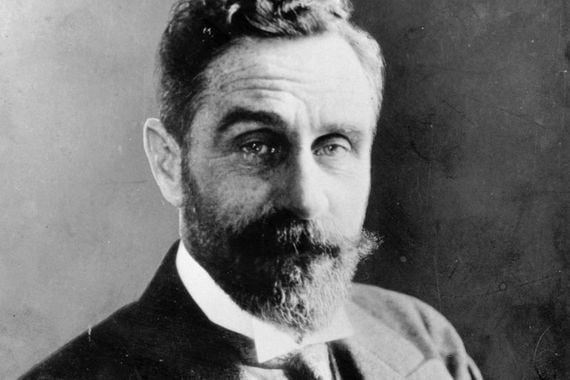

Sir Roger Casement, the enigmatic patriot

Roger Casement, in the long history of Irish patriots, may have been the most enigmatic of them all. The British thought of him as a traitor, and many in the Republican movement had a deep distrust of him, including Tom Clarke, the mastermind behind the Easter Rising. But others in the movement had a deep affection for him, including Joseph Mary Plunkett, a signatory of the Easter Proclamation and, oddly enough, tough John Devoy in New York, a man who did not suffer fools easily. Devoy took a liking to him and advanced the money that would take Casement to Germany in search of men and munitions. It was from Germany that Casement would voyage back to Ireland via U-boat, be arrested in County Kerry, and have his Stalin-style show trial in London in June 1916.

Casement was famous for uncovering atrocities against the natives of the Belgian Congo and was rewarded for it with a knighthood. It was through the celebrity that he became friends with Doyle and Shaw.

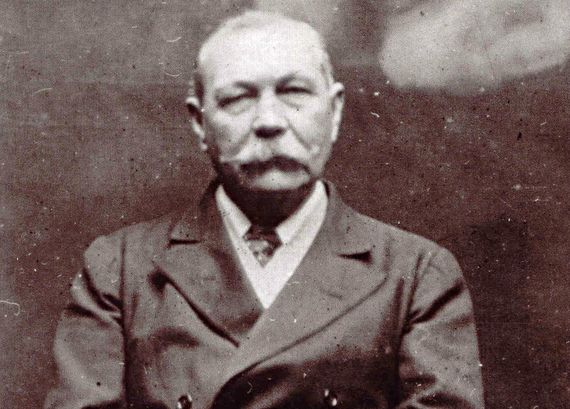

Arthur Conan Doyle was born on May 22, 1859, to Charles Doyle and the former Mary Foley in Edinburgh, Scotland. His grandfather, John Doyle, was, according to John Dickson Carr in The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “…of the Irish Catholic landed gentry, [who] had come to England from an estate ruined by generations of penal laws against Catholics. His family was of old Norman descent and had been granted estates in Ireland in the first half of the 14th century.” His mother Mary was the “[y]ounger daughter of an Irish Catholic widow.”

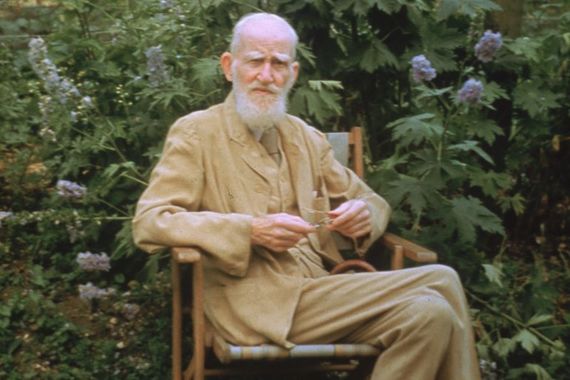

George Bernard Shaw was born at #33 Synge Street in Dublin on July 26, 1856, of Protestant stock. In 1924, he became one of four Irishmen [Yeats, Beckett and Heaney are the others] to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Along with his fellow Dublin Protestants, Sean O’Casey and Samuel Beckett, he would make an artistic impression not only on Ireland but also around the globe as one of the great playwrights of the 20th century.

Read more

The Casement-Doyle connection

Arthur Conan Doyle.

Casement earned his knighthood for exposing atrocities against the natives of the Belgian Congo. This brought him to the attention of Doyle, who became very involved in the exposé against the policies of King Leopold of Belgium.

According to Roger Casement: The Biography of a Patriot Who Lived for England, Died for Ireland by Brian Inglis, in 1909 Doyle published The Crime of the Congo which reminded “readers of the full horror of Leopold’s system, as exposed by Casement—‘a man of the highest character, truthful, unselfish—one who is deeply respected by all who know him.’ ”

Their relationship grew from there, even as Casement drifted away from England and became active in the Republican movement. Inglis writes that “By Casement’s account…he had converted Doyle from Unionism to Home Rule.” Doyle stood by his friend even as most of Britain came to despise Casement for his German adventure in time of war. “When the Daily Chronicle described his German adventure as ‘an infatuation,’ ” wrote Inglis, “Conan Doyle praised them for not having fallen a victim to the temptation to use a stronger term. Conan Doyle had greatly admired him: ‘You have done so much good in your life,’ he had written to him prophetically in 1912, ‘that no shadow should in justice come near you.’ ”

After Casement’s conviction, Doyle put together a petition which was signed by 39 prominent Englishmen calling upon Prime Minister Asquith to commute Casement’s sentence from death to life imprisonment.

“Meanwhile,” wrote John Dickson Carr in The Life of Arthur Conan Doyle, “[Doyle] had tried to save the life of Roger Casement…The erstwhile patriot, his shrunken features ivory-white under the beard, stood in the dock on a self-confessed charge of treason.”

Carr is not sympathetic to Casement, which he makes plain: “It is difficult to sympathize with Casement in anything except his idealism.” But he goes on to say: “But he was honest, thoroughly honest, even when he took the pay of Germany and landed in Ireland to stir up rebellion there. Conan Doyle believed—not without reason—that the man was mentally as well as physically ill from his years in the tropics.”

“ ‘Don’t hang him!’ urged the champion of lost causes [Doyle], who hated to see any underdog strung up. ‘Sentence him to any form of imprisonment you like. Spare his life. He is not fit to plead.’ ”

“But to acknowledge the validity of Casement’s plea would have been to acknowledge Ireland as a free state at war with Britain. They hanged him at Pentonville; they could do nothing else; and the din of the Somme bombardment grew even louder.”

Doyle’s treatise was titled “A Petition to the Prime Minister on Behalf of Roger Casement.” It is an odd document because he does not deny Casement’s guilt or try to assuage the facts of the case.

Doyle begins: “Sir,—We, the undersigned, while entirely admitting the guilt of the prisoner Roger Casement, and the justice of his sentence, would desire to lay before you some reasons why the extreme sentence of the law should not be inflicted—”

Doyle first argument is, well, to put it bluntly, Casement is nuts: “We would call attention to the violent change which appears to have taken in the prisoner’s sentiments towards Great Britain (as shown, for example, in his letter to the King at the time of his knighthood) from those which he had exhibited during the war. Without going so far as to urge complete mental irresponsibility, we should desire to point out that the prisoner had for many years been exposed to severe strain during his honourable career of public service, that he had endured several tropical fevers, and that he had experienced the worry of two investigations which were of a peculiarly nerve-trying character. For these reasons, it appears to us that some allowance may be made in his case for an abnormal physical and mental state.”

Read more

Doyle’s next ploy is to state that the hanging of Casement would not be good PR for Britain in Ireland and Irish-heavy America: “We would urge that his execution would be helpful to German policy, by accentuating the differences between us and some of our fellow subjects in Ireland. It would be used, however unjustly, as a weapon against us in the United States and other neutral countries. On the other hand, magnanimity upon the part of the British Government would soothe the bitter feelings in Ireland, and make a most favourable impression throughout the Empire and abroad.”

And in conclusion, he brings Abraham Lincoln’s policy towards the defeated South into the fray and begs for mercy: “We would respectfully remind you of the object lesson afforded by the United States at the conclusion of their Civil War. The leaders of the South were entirely in the power of the North. Many of them were officers and officials who had sworn allegiance to the laws of the United States and had afterwards taken up arms and inflicted enormous losses upon her. None the less not one of these men was executed, and this policy of mercy was attended by such happy results that a breach which seemed to be irreparable has now been happily sealed over.”

The petition declares that it was created at Bushwell’s Hotel, Dublin, 15th July, 1916. Among the 39 signatories are Doyle himself and writers G.K. Chesterton, John Galsworthy and John Masefield. It is notable that George Bernard Shaw did not sign the document. The petition, as might be expected, had no effect on Prime Minister Asquith.

The Casement-Shaw connection

George Bernard Shaw.

“Connections between Shaw and Casement,” wrote Angus Mitchell in Casement, “can be traced to John Bull’s Other Island, a work to which Casement frequently referred in his prison writings.”

Mitchell goes on to say that “Casement’s most active ally was George Bernard Shaw. Although Shaw was a critic of Sinn Féin, his sympathies were changed by the secret military tribunals and the execution of the 1916 leaders, which, he felt, played directly into the hands of the extremists.”

“Shaw had high hopes for Casement’s defense,” wrote Mitchell, “not least a desire to write a plan for his defense and his speech from the dock in a way that would leave little doubt of the conflict of allegiances facing the Irish as a result of the war. In his astute summary of the legal options, Shaw suggested that Casement had three possible lines of defense: he could plead insanity for which medical evidence would be required; he could throw himself at the mercy of the court and plead leniency based on his prior service and reputation; or he could admit to what he had done, arguing that he acted out of duty for his country and that foreign aid and the co-operation of the German empire was vital to Irish independence. It was this line that Shaw recommended and Casement developed.”

“Casement was in pursuit of the martyr’s crown and his prison writings began to chart his own path towards this desired end. His very ‘rebellion’ and the cause of Irish freedom would, he hoped, be discussed in detail at his trial.”

“Shaw had been the first to warn the British public,” wrote Brian Inglis in Roger Casement, “in a letter to the Daily News that the inevitable consequence of the executions would be to hand Ireland over to Sinn Féin. He himself, he explained, had been a consistent critic of Sinn Féin—one of his attacks on the movement had appeared in the Irish Times only two days before the rising. And he had disagreed even more strongly with those nationalists who looked to Germany as a liberator. But the news of the executions appalled him. They had done what the rising itself had failed to do: ‘it is absolutely impossible to slaughter a man in this position without making him a martyr and a hero, even though the day before the rising he may have been only a minor poet. The shot Irishmen will now take their places beside Emmet and the Manchester Martyrs in Ireland, and beside the heroes of Poland and Serbia and Belgium in Europe; and nothing in heaven or earth can prevent it.’

Read more

“And although to name Casement might have landed him in trouble for contempt of court, he made an oblique reference to the case: ‘I remain an Irishman; and I am bound to contradict any implication that I can regard as a traitor any Irishman taken in a fight for Irish independence against the British Government.’ ”

And like Doyle tried to do with his petition to the Prime Minister, Shaw wrote to the Manchester Guardian (after it was rejected by the Times of London) on July 22nd, only two weeks before the scheduled execution, with an essay entitled “Shall Roger Casement Hang?” And like Doyle’s petition, this essay takes some strange stands.

First, Shaw makes clear that he is not British: “may I, as an Irishman, be allowed to balance their judgment…” He then goes on a strange tangent about hanging: “I will go so far as to confess that there is a great deal to be said for hanging all public men at the age of fifty-two, though under such a regulation I should myself have perished eight years ago. Were it in force throughout Europe, the condition of the world at present would be much more prosperous.”

Is he being Swiftian in a Modest Proposal way? Or coarse? After all he is talking about a man’s life that is hanging in the balance here. It is an odd beginning for a treatise trying to save a man’s life.

Inglis in his Casement biography tries to explain this strange note: “…recalling that although Casement had had a fair trial, the Defence had failed to raise certain important issues—the treason of the Unionist leaders over Ulster, for one: what about those unconvicted and indeed unprosecuted traitors, whose action, helped very powerfully to convince Germany that she might attack France without incurring our active hostility? The jury too, ought to have been shown that Ireland’s being a part of the United Kingdom no more prohibited Casement from doing what he had done, than five centuries of Turkish rule in the Balkans had abrogated the right of the Serbian to fight for his country’s independence. And it ought to have been emphasized to them that the fact Casement had been in the pay of the British Government did not make him a traitor to Britain, any more than Shaw’s acceptance of thousands of pounds in royalties from Germany (far more, he remarked, than he had received from British sources) made him a traitor to Germany. But his essential point was that Casement would be regarded in Ireland as a national hero, if he was executed—‘and quite possibly as a spy, if he is not. For that reason, it may very well be that he would object very strongly to my attempt to prevent his canonization. But Ireland has enough heroes and martyrs already, and if England has not by this time had enough of manufacturing in fits of temper, experience is thrown away on her.’ ”

Shaw concludes his letter by stating: “The reasonable conclusion is that Casement should be treated as a prisoner of war. I believe this is the view that will be taken in the neutral countries, whose good opinion is much more important to us than the satisfaction of our resentment. In Ireland, he will be regarded as a national hero if he is executed, and quite possibly as a spy if he is not. For that reason,n it may well be that he would object very strongly to my attempt to prevent his canonization. But Ireland has enough heroes and martyrs already, and if England has not by this time had enough of manufacturing them in fits of temper, experience is thrown away on her, and she will continue to be governed, as she is at present to so great an extent unconsciously, by Casement’s countrymen.”

“Irish Outlaw” Casement in the dock

Roger Casement.

Both Doyle and Shaw failed miserably in their attempt to save Casement. Perhaps Casement’s best defense came from himself, in the dock, as he pulled a Robert Emmet, speaking powerfully in his, and Ireland’s, defense.

Casement in his statement proclaims himself an “Irish Outlaw” and says that he is “proud to be a rebel.” He swiftly casts doubt on the legitimacy of a British court trying an Irish patriot: “I am being tried, in truth, not by my peers of the live present, but by the peers of the dead past; not by the civilization of the twentieth century, but by the brutality of the fourteenth; not even by a statute framed in the language of an enemy land—so antiquated is the law that must be sought today to slay an Irishman, whose offence is that he puts Ireland first. Loyalty is a sentiment, not a law. It rests on love, not on restraint. The Government of Ireland by England rests on restraint and not on law; and since it demands no love it can evoke no loyalty. But this statute is more absurd even than it is antiquated, and it is potent to hang one Irishman, it is still more potent to gibbet all Englishmen.”

Casement asserts the court is a fraud: “With all respect I assert this Court is to me, an Irishman, not a jury of my peers to try me in this vital issue for it is patent to every man of conscience that I have a right, if tried at all, under this statute of high treason, to be tried in Ireland, before an Irish Court and by an Irish jury.”

He goes on to take on John Redmond—without mentioning him by name—of the Irish Parliamentary Party and his dual buffoonery of accepting a suspended Home Rule and urging young Irishmen to join the British Army so they could be slaughtered: “And now that we were told the first duty of an Irishman was to enter that army, in return for a promissory note, payable after death—a scrap of paper that might or might not be redeemed, I felt over there in America that my first duty was to keep Irishmen at home in the only army that could safeguard our national existence. If small nationalities were to be the pawns in this game of embattled giants, I saw no reason why Ireland should shed her blood in any cause but her own, and if that be treason beyond the seas I am not ashamed to avow it or to answer for it here with my life.”

“We are told that if Irishmen go by the thousand to die, not for Ireland, but for Flanders, for Belgium, for a patch of sand on the deserts of Mesopotamia, or a rocky trench on the heights of Gallipoli, they are winning self-government for Ireland. But if they dare to lay down their lives on their native soil, if they dare to dream even that freedom can be won only at home by men resolved to fight for it there, then they are traitors to their country, and their dream and their deaths alike are phases of a dishonorable phantasy. But history is not so recorded in other lands. In Ireland alone in this twentieth century is loyalty held to be a crime. If loyalty be something less than love and more than law, then we have had enough of such loyalty for Ireland or Irishmen. If we are to be indicted as criminals, to be shot as murderers, to be imprisoned as convicts because our offence is that we love Ireland more than we value our lives, then I know not what virtue resides in any offer of self-government held out to brave men on such terms. Self-government is our right, a thing born in us at birth; a thing no more to be doled out to us or withheld from us by other people than the rights to life itself—than the right to feel the sun or smell the flowers, or to love our kind. It is only from the convict these things are withheld for crimes committed and proven—and, Ireland, that has wronged no man, that has injured no land, that has sought no dominion over others—Ireland is treated today among the nations of the world as if she was a convicted criminal. If it be treason to fight against such an unnatural fate as this, then I am proud to be a rebel, and shall cling to my ‘rebellion’ with the last drop of my blood.”

Roger Casement goes home to Ireland

There is a postscript to this story. In 1965, 49 years after his execution, Roger Casement was disinterred from the yard at Pentonville Prison and his remains were returned to Ireland. An Taoiseach, Seán Lemass, had negotiated the return of Casement with British Prime Minister Harold Wilson. “I am very glad to announce to the Dáil,” Lemass said, “that I have been informed by the British Prime Minister that his Government have recently decided to meet our request for the repatriation of the remains of Roger Casement. As Deputies are aware, it was Casement’s express wish that he should have his final resting place in Ireland, and it has long been the desire of the people of Ireland, shared by successive Irish Governments, that this wish be fulfilled.”

Casement was given a state funeral and President Eamon de Valera gave the eulogy at the gravesite in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin. “It required courage to do what Casement did,” said de Valera, “and his name would be honoured, not merely here, but by oppressed peoples everywhere, even if he had done nothing for the freedom of our own country.”

Roger Casement was home at last.

* Dermot McEvoy is the author of the The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising and Our Lady of Greenwich Village, both now available in paperback, Kindle and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/13thApostleMcEvoy.

** This article was originally published in 2018 and updated in Sept 2025.

Comments