"To America, my new-found land. The man that hates you hates the human race" - Brendan Behan

The below is an excerpt from Dermot McEvoy's latest book "Real Irish New York" from Skyhorse Publishing.

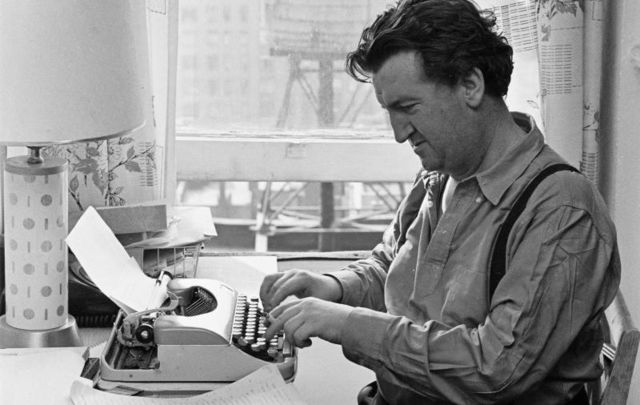

Brendan Behan was an addict. He was addicted to two things—booze and New York City. Together, in less than four years, they would combine to kill him at the ridiculously young age of forty-one. To put it mildly, Behan and drink did not mesh. And he seemed to know it. “One drink is too many for me,” he once said, “and a thousand not enough.”

New York has always acted as a magnet for the Irish. Behan was no different. Most people think of Behan as the quintessential Dubliner—and he was. But New York could give Behan what Dublin couldn’t—fame and fortune. He loved the attention as much as he loved the taste of booze.

Ulick O’Connor in his revealing biography of Behan, Brendan, said, “While he was sober in New York, Brendan was happier than he had been anywhere else, except Dublin. He found certain literary circles there congenial and less inhibited than in London. The artist seemed to have fewer layers of encrusted social background to break through in order to find himself.”

Understanding Behan

Behan was born into the slums of Northside Dublin on Russell Street—although it should be pointed out that the tenement he grew up in was owned by his granny. To understand Behan the writer, I think one must understand his virulent Republican background.

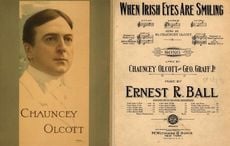

His mother Kathleen’s brother, Peadar Kearney, wrote the Irish national anthem, “Amhrán na bhFiann,” (“The Soldiers’ Song”) and his father was in the IRA, most prominently helping to burn down the Custom House in Dublin in 1921. While his father was imprisoned, his mother went to see Michael Collins in search of money.

Read more

She always called Collins her “Laughing boy.” Behan remembered that and at the age of thirteen, penned the sweet and gentle poem, “The Laughing Boy,” about Collins’s death:

’Twas on an August morning, all in the dawning hours,

I went to take the warming air, all in the Mouth of Flowers,

And there I saw a maiden, and mournful was her cry,

“Ah what will mend my broken heart, I’ve lost my Laughing Boy.”

At the age of sixteen, as a member of the IRA, he went to England with plans for blowing up a Royal Navy destroyer. He was apprehended and sent to a borstal for boys, memories of which, years later, he turned into the compelling autobiographical Borstal Boy. In 1941, he was locked up again, this time by the Irish, for gunplay in Glasnevin Cemetery. He was released five years later in an amnesty and began his life for real. He worked as a house painter and started writing.

But his writing was always infected by his desire to drink. His three greatest works were written before liquor grabbed him by the knees. Borstal Boy is a superb book, full of insights, howls, and absolutely beautiful writing. His two plays, The Quare Fellow, about a man—the “quare” fellow himself—about to be hanged, and The Hostage, about a British soldier held by the IRA as a prisoner, are also superior works. The Quare Fellow was made into a movie in 1962, starring the American actor Patrick McGoohan. The Quare Fellow also contains one of the most beautiful songs, written by Behan himself, “The Old Triangle,” about the lonely life of an inmate in Mountjoy Gaol.

Brendan Behan discovers New York - and vice versa

Behan landed in New York for the Broadway premiere of The Hostage in September 1960. “Brendan staged his arrival superbly,” wrote Ulick O’Connor in his Behan biography. “He got off the ship with a bottle of milk in his hand. ‘I’m on the wagon,’ he told reporters. ‘It’s not easy to smile when you’re drinking this stuff. I may need a stomach pump.’ ”

The play was a hit and it, and its author seemed to energize the Big Apple at the end of the Sominex Eisenhower era: “New York was dead in those days,” O’Connor quoted Norman Mailer in his biography. “It was the end of the Eisenhower regime, a puritan period. Brendan’s Hostage broke the ice. It was a Catholic Hellzapoppin. It made the beatnik movement—Kerouac, Ginsberg, myself and others—respectable uptown. Before Brendan, we were in exile down in the Village. The Hostage was adored because of its outrageousness and its obscenity, and because of Brendan’s captivating humour and personality. He was an ice-breaker, and the times needed an ice-breaker.”

He would return to the city for periods of time over the next three years. He took to the city—and the city took to Behan. He was a celebrity, appearing on TV with the likes of Jack Paar, David Susskind, and Jackie Gleason. This was the celebrity-gilded life he had been seeking.

Behan’s first New York go-around in 1960 went relatively well. The only incident was when he took to the stage drunk at the Cort Theatre, but he thought that sort of thing helped sell tickets. He went home to Dublin at Christmastime and returned to New York in February 1961. There was an incident in Canada where he was jailed for public drunkenness, and he was banned from New York’s St. Patrick’s Day parade by Judge John J. Comerford, ironically an ex-IRA man himself, for being a “disorderly person.” But Behan, a master of the media, turned the episode with a positive spin. “There are three things I don’t like about New York,” O’Connor quotes him in his biography, “the water, the buses and the professional Irishman. A professional Irishman was one who was terribly anxious to pass as a middle-class Englishman.” Take that, Judge Comerford!

He was invited to the Jersey City St. Patrick’s Day Parade by Mayor Witkowski and given the key to the city. Behan responded with the classic line: “At the end of the Holland Tunnel lies freedom. I chose it.”

Trying to write in New York

Without a doubt, the best descriptions of Behan in New York are supplied by his editor at Hutchinson Publishers in London, Rae Jeffs, in her superb book Brendan Behan: Man and Showman. It is a no-holds-barred biography that will have you marveling at Jeff’s Job-like (and job-like) patience.

“It was inevitable that Brendan should fall in love with New York,” wrote Rae Jeffs, “for it was nearer to his dream of Never-Never-Land than he would ever find elsewhere: a city which never appears to go to sleep, and a fancy fair of brilliant lights where at any time of the day or night he could walk without fear of being lonely. His restless and inquisitive personality found a thousand avenues to explore, and always a friendly face to accompany him, to sit and enjoy a cup of coffee or a glass of orange juice whenever he felt the need.” She went on to add that “the Americans love a celebrity and he was very high up on their list.”

Jeffs had been working with Behan since Hutchinson had published Borstal Boy in 1957. She was sent to New York to get three books—Brendan Behan’s Island, Confessions of an Irish Rebel, and Brendan Behan’s New York—out of him. She soon realized that his “appalling thirst,” as she called it, had destroyed any discipline he may have once had as a writer.

Read more

“He certainly never read the two books which were produced by means of the tape-recorder,” wrote Jeffs, “Brendan Behan’s Island and Brendan Behan’s New York, nor would he even edit the raw material. And he died before the tapes of Confessions of an Irish Rebel had been fully transcribed. He was ashamed that he had lost the willpower and the concentration to work and was forced to resort to book-making in this manner.” It is not surprising that Jeffs titled her chapter on Behan in New York: “America: Triumph and Disaster.”

By 1963, Jeffs found herself working at the Chelsea Hotel with a Behan totally out of control. His wife, Beatrice, was also in New York and pregnant with their first child. The work on Brendan Behan’s New York was going poorly.

The alcohol, diabetes, and liver ailments had begun to take their toll and his health began to deteriorate with alcoholic seizures. He was removed to a hospital and at one point thought he was in Grangegorman, the Dublin lunatic asylum.

By the fall of 1963, he was back in Dublin. “On the few occasions that he spoke,” wrote Jeffs, “he made it clear that his chief regret at leaving the city of his heart was a persistent doubt that he would ever see it again. Indeed, the extent of his affection for New York was such that for the first time he made no attempt to drown his sadness, but preferred to savour and remember soberly his last remaining hours in the place.”

The fall of ’63 was very traumatic for Behan. Jeffs tried to get as much of Brendan Behan’s New York on tape as she could and became not only its editor, but its writer. “Using Borstal Boy as my guide,” she wrote, “I would pace the floor in an endeavour to force myself to become a second-rate understudy.”

On Friday, November 22, 1963, Brendan Behan’s New York was finished, and they went out to celebrate at the Bailey restaurant in Duke Street. They were soon to learn that John F. Kennedy had been assassinated that day in Dallas. Two days later, on November 24, Behan’s only child, Blanaid Orla Mairead, was born. In thanks for all the work she had done with Brendan, Rae Jeffs was made the child’s godmother.

Brendan’s time was limited; he knew it, and continued to drink in any pub—and there weren’t many—that would allow him on the premises. Less than four months after his daughter’s birth, he was dead.

The Gay Behan

The big revelation of Ulick O’Connor’s biography was that Behan was bisexual.

“There was a YMCA gymnasium across the road and . . . Behan went there regularly for work-outs,” wrote O’Connor. “Brendan would punch the bag inexpertly but vigorously, do some press-ups and swim interminably up and down the pool. Afterwards, he would sweat it out in the steam bath, his eyes lighting up, a member recalls, as he saw young men pass by naked on their way to the shower.”

In Brendan Behan’s New York, Behan reveals part of his YMCA life: “I am extremely fond of swimming and opposite the Hotel Chelsea is the Young Men’s Christian Association where I used to swim quite a deal. And they have a rule that you cannot wear bathing trunks and before you dive into the pool, you have to take an ankle bath and you have to take a soap shower.”

“At this time he was never sure that some enterprising journalist would not spring the story of his affair in New York,” continued O’Connor. “This explanation would be used in Ireland to explain his frequent visits to America. His past homosexual encounters might be raked to the surface. Brendan was still hot news, and any hint of scandal would be amplified a hundred times.”

“In New York in his last year,” said O’Connor, “he would sometimes ask an acquaintance to arrange a rendezvous with negro youths who took his fancy, but would always fail to turn up himself for the appointment.”

In Brendan Behan’s New York, he has a whole paragraph on homosexuality, prompted by a visit to Fire Island. It is a little disturbing that he sees the age of consent at only fourteen. “Later that evening,” he wrote, “somebody asked me if I was a homosexual, because apparently Cherry Grove, a part of the Island near to where we were staying, was a sort of haven for these fellows. Now I think that people have much more to trouble them than how adults behave. I am of course of the opinion, like every reasonable man, that any kind of sex with any sort of interference with kids, of say under fourteen, should be prohibited by law. There is no point in talking about homosexuality as if it were a disease. I’ve seen people with homosexuality and I’ve seen people with tuberculosis and there is no similarity at all. My attitude to homosexuality is rather like that of the woman who, at the time of the trial of Oscar Wilde, said she didn’t mind what they did, so long as they didn’t do it in the street and frighten the horses. I think everyone agrees that with young people it is a bad thing for society, but amongst consenting adults, it is entirely their own affair.”

The End

Behan died at the Meath Hospital in Dublin on March 20, 1964. The New York Times in their obituary reported the cause of death as “diabetes, jaundice and kidney and liver complaints—aggravated by his renowned bouts with drink.”

And after his battles with the Church, he would, of course, die a Catholic death. “I suppose I am inclined to believe in all that the Catholic Church teaches,” he once told the New York Herald Tribune. “I am accused of being blasphemous, but blasphemy is the comic verse of belief. I am a religious man only when I am sick or up in an aeroplane. On the aeroplane coming over, a nun sat next to me. There were moments when I felt like snatching the Rosary Beads out of her hand and doing a little prayer myself.”

“When I die, I want to die in bed surrounded by fourteen holy nuns with candles,” he once said. “I am a Catholic. A damn bad on,e according to some. But I have never ridiculed my faith. Even when the drink takes to me I find that when darkness falls I think of my prayers.”

“To those who regarded him with disdain,” the New York Times noted, “a view held among some Irish intellectuals—he was a stage Irishman, a strange mixture of the naive and the sophisticated. His plays were looked upon as a shapeless collection of bright quips that could be given polish only by a talented director. To his admirers, who are many, he was a writer of immense talent, capable of transferring people live and warm from their natural habitat to the stage or printed page.”

Whatever you think of Brendan Behan, he was a unique talent and personality. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. I have seen his grave. It is close to the south gate, which is right outside John Kavanagh’s Gravediggers Pub. Somehow, I feel that Brendan rests easier because of this friendly juxtaposition.

Read more about it in Real Irish New York, which is available in hardcover and Kindle from Amazon.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of the recently published "Real Irish New York: A Rogue’s Gallery of Fenians, Tough Women, Holy Men, Blasphemers, Jesters, and a Gang of Other Colorful Characters." He is also the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising," and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," both now available in paperback, Kindle and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website or on Facebook.

* This article was originally published in 2020, updated in 2025.

Comments