Michael Collins departed Dublin on August 20, 1922, beginning what would become his fateful final hours alive.

When he left Dublin, he was ill and feverish, and his doctor recommended that the trip be postponed.

Had he merely been going on an inspection trip, it could have been delayed, but it appeared Collins had something more in mind.

August 20, 1922

Collins’s convoy left Portobello (now Cathal Brugha) Barracks, Dublin, at 5:15 am on Sunday, August 20, and made its first stop at Maryborough Jail (now Portlaoise Prison), where Collins discussed transferring some of the prisoners there to Gormanstown camp to relieve the overcrowded conditions.

He also spoke with some of the prisoners, including Tom Malone, about ending the Civil War. He asked if Malone would attend a meeting to “try to put an end to this damned thing.” As he left, he slapped one fist into his hand and said, “that fixes it—the three Toms [Malone, Tom Barry, and Tom Hales] will fix it.”

Then the convoy headed to Roscrea Barracks for an inspection and breakfast. At Limerick Barracks, the Officer/Commanding (O/C) of the Southern Command, General Eoin O’Duffy, met Collins and discussed his belief that the Civil War would soon be over and understood that Collins wanted to avoid any rancor. The convoy then headed through Mallow and spent that night in Cork City, where he stayed at the military HQ in the Imperial Hotel.

That evening, Collins met his sister, Mary Collins-Powell, and her son, Seán, and the rest of the evening was spent in consultation with the O/C of the area, Gen. Emmet Dalton. Dalton felt that “normality and law and order would not be too far off. We were in possession of the principal towns in County Cork. Michael Collins and I discussed this on the journey through West Cork.” Most of the escort spent the first evening in the Victoria Hotel.

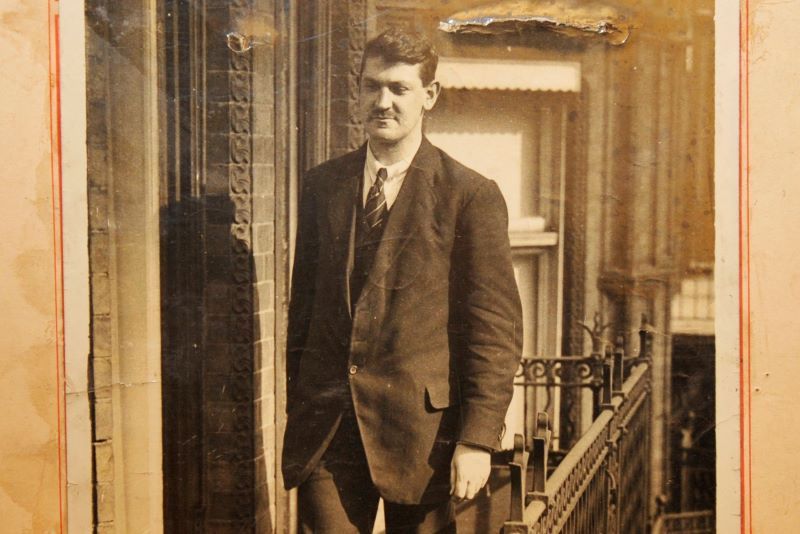

A photograph of Michael Collins (RollingNews.ie)

August 21, 1922

On Monday, August 21, Collins again visited with his sister, and then he and General Dalton went to the Cork Examiner to discuss the general Free State position on publicity with the editor, Tom Crosbie. Collins also visited some local banks in an effort to trace republican/IRA/anti-Treaty funds lodged during their occupation of the city.

First, they visited the Hibernian Bank, then the Bank of Ireland, then the Land Bank, and finally other smaller institutions to try to recover the funds. During July, the IRA collected £120,000 in customs revenue and had hidden this money in the accounts of sympathizers.

At each bank, Collins told their managers to close the doors, and they would allow the banks to be reopened only if the managers cooperated fully. Collins had the bank directors identify the suspicious accounts, then he concluded that “three first-class men will be necessary to conduct a forensic investigation of the banks and the Customs and Excise in Cork.” He told William Cosgrave to consider three people but “don’t announce anything until I return.”

He and Dalton then traveled the thirty miles to Macroom where Collins met Florence O’Donoghue, who was in the IRA and was one of its leaders in County Cork in the War of Independence, but who was neutral in the Civil War. The first phase of the Civil War was ended, O’Donoghue later wrote. He and many others recognized at this point that the IRA/Republicans could not win the war and that Collins came south searching for peace.

Collins was desperately trying to bring the War to a close, as well as trying to give some face-saving agreement to the leaders on the other side. It is thought that he asked O’Donoghue how to stop the War and to mediate for him. After lunch at the Imperial, they headed out to review the military in Cobh, and then returned to Cork in early evening.

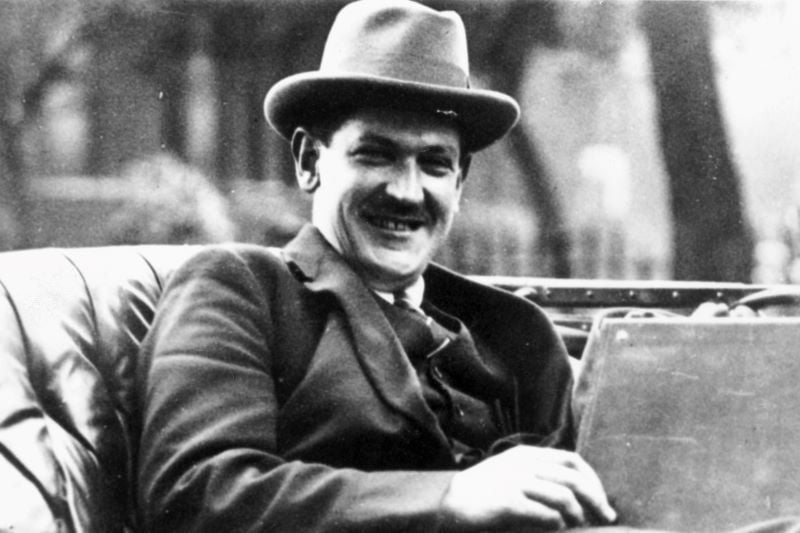

Michael Collins at the wedding of Commander Sean McKeown (The Blacksmith of Ballinalee) and Miss A Cooney in June 1922 (Getty Images)

August 22, 1922 - The Fateful Day

Collins’s party left the Imperial Hotel, Cork, at 6.15 am on Tuesday, August 22.

That day, the convoy included the following:

A motorcyclist, Lt. John ‘Jeersey’ Smyth.

A Crossley Tender under the command of Cmdt. Seán (Paddy) O’Connell, Capt. Peter Conlon, Sgt. Conroy, Sgt. Cooney, John O’Connell, and eight riflemen, Gough, Barry, Carmody, Coote, Edmunds, Murray, Caine, and McKenna.

Collins and Emmet Dalton in a yellow Leland Thomas Straight Eight touring car.

The driver was Private Michael Smith Corry and the reserve driver was M. Quinn.

A Rolls Royce Whippet armored car (A.R.R. 2), the Slievenamon. Capt. Joe Dolan was riding in the car. Jim Wolfe was the driver, Jimmy ‘Wiggy’ Fortune the co-driver. The Vicker’s machine-gunner on the armored car was John (Jock) McPeak. (He deserted on December 2, 1922, with Billy Barry and Pat and Mick O’Sullivan and took the armored car to the IRA; he said he did it for a woman. He was arrested in Glasgow in July 1923 and was imprisoned in Portlaoise where he went on a hunger strike). Cooney and Monks were the other members of the armored car crew.

The military detail was far too small for the protection of the Free State Commander-in-Chief, especially as they would be traveling through some of the most active anti-Treaty areas of south Cork.

The convoy went through Macroom towards Béal na mBláth about 8 am where it stopped to get directions, then through Crookstown, then to Bandon.

In Bandon, Collins briefly met in Lee’s Hotel with Major General Seán Hales, O/C of the Free State forces in West Cork. It is thought that Hales was informed of a meeting Collins had intended with Civil War neutrals in Cork that evening and that he had met with O’Donoghue and others the day before and discussed how an end to the War could be achieved.

At Clonakilty, the convoy stopped for lunch at Callinan’s Pub.

In the afternoon the convoy went to Roscarberry and Collins had a drink in the Four Alls Pub (owned by his cousin Jeremiah) at Sam’s Cross where Collins declared: “I’m going to settle this thing. I’m going to put an end to this bloody war.”

But there is no sign he was open to compromise. Clearly, any hope he had of settling the Civil War would not be done at the expense of the Treaty. Collins told his brother, Johnny, that he would “go further with the British government once there was peace here.” His principal aim was to end the Civil War. He said “The British have given up their claim on us. When we begin to work together we can help those in the northeast.”

On the way back, Collins’s party passed by the burnt remains of his childhood home, Woodfield, and Collins pointed to the rugged stone walls.

“There,” he said to Dalton, “There is where I was born. That was my home.”

Still, Collins was as happy as Dalton had seen him.

“He was able to let himself go, and also I think he felt things were now moving his way. He didn’t say much as we traveled along the flat road towards Bandon, he appeared lost in the myriad thoughts of a crowded and successful day.”

The convoy left the Eldon Hotel in Skibbereen at 5 pm and headed back to Cork. Collins met his great friend John L. Sullivan on this journey. The convoy detoured around Clonakilty on the way back because of a roadblock. It stopped at Lee’s Hotel in Bandon for tea. (It has never been fully explained why the convoy returned this same way they came out in the morning, however when the anti-Treaty forces left Cork city they blew up most of the bridges and cut most of the roads, so there were few passable ways to travel in County Cork.) There, again, he met Hales, who was the brother of Tom Hales, by coincidence a member of the ambush party. “Keep up the good work! ’Twill soon be over” was Collins’s parting salute to Hales.

On the road out of Bandon, Collins said to Dalton; “If we run into an ambush along the way, we’ll stand and fight them.” Dalton said nothing.

In the early morning of Tuesday, August 22, the ambush party met in Long’s Pub (owned by Denis “Denny the Dane” Long, the “lookout” who spotted Collins’s party as it passed through Béal na mBláth).

The men who assembled at Béal na mBláth were not a column, but officers trained in guerrilla warfare who gathered to hold a pre-arranged important staff meeting. When Florence O’Donoghue met with the surviving members of the IRA/Republicans in 1964, they said they were unaware that Collins was in the area until that morning. The plan to ambush the party was decided as part of the general policy of attacking all Free State convoys, not as a specific plan to ambush this convoy. They saw the opportunity to overpower an enemy convoy on its return journey and they decided to take up the challenge and ambush it.

The IRA/Republicans stopped a Clonakilty man, Jeremiah O’Brien, who was taking a cartload of empty mineral bottles to Bandon. They commandeered his cart and took off one of the wheels, blocking the road. In combination with the mine they were placing in the road, the ambush party knew the convoy would have to stop abruptly. The ambush party remained in place all day, but there was no action. In the late afternoon, a message was received that Collins’s party was in Bandon, but as it was thought unlikely that the convoy would come through Béal na mBláth a second time, they began to disassemble the mine and evacuate the position.

Michael Collins (Getty Images)

The ambush of Michael Collins

Originally, the ambush party numbered between 25 and 30, according to varying sources. Some men stayed all day, others came and went as the day went on.

The ambush took place at Béal na mBláth (between Macroom Crookstown, about ten miles short of Bandon) just before sunset, at 7.30 pm. When the first shots were fired, Dalton ordered: “Drive like hell.” Collins countermanded the order just as he had predicted and yelled: “Stop, we’ll fight them.”

Collins and Dalton first fired from behind the armored car, and then Collins shouted “there—they are running up the road.” The Lewis machinegun in the armored car jammed several times, and when it did the IRA/Republicans took advantage of the lull in firing to move their positions.

Then, Collins ran about fifteen yards up the road, dropped into a prone firing position, and continued shooting at the IRA/anti-Treatyites on the hill.

Dalton said then he heard the faint cry “Emmet, I’m hit.” Dalton and Commandant Seán O’Connell ran over to where Collins was lying face-down on the road and found a “fearful gaping wound at the base of his skull behind the right ear. We immediately saw that General Collins was almost beyond human aid. He could not speak to us. …O’Connell now knelt beside the dying, but still conscious, Chief whose eyes were wide open and normal, and whispered into the ear of the fast-sinking man the words of Act of Contrition. For this he was rewarded with a light pressure of the hand. …. Very gently I raised his head on my knee and tried to bandage his wound but owing to the awful size of it this proved very difficult. I had not completed this task when the big eyes quickly closed, and the cold pallor of death overspread the General’s face. How can I describe the feelings that were mine in that bleak hour, kneeling in the mud of a country road not twelve miles from Clonakilty, with the still bleeding head of the Idol of Ireland resting on my arm.”

Later Dalton said: “it was a very large wound, an open wound in the back of the head …and it was difficult for me to get a First-Field-Aid bandage to cover it, you know when I was binding it up. It was quite obvious to me, with the experience I had of a ricochet bullet, it could only have been a ricochet or a dum-dum.”

Michael Collins at the Curragh Barracks in Co Kildare with Col Dunphy, Major General Emmet Dalton, Comdt-Gen P MacMahon, and Comdt-Gen D O'Hegarty in July 1922 (Getty Images)

After the ambush

The ambush was over in approximately thirty minutes, and before it ended, darkness had fallen so it was impossible to get off an aimed shot. No one in the anti-Treatyite party fully knew that Collins had been shot or that the convoy suffered any casualty. It was only when Shawno Galvin came back to Béal na mBláth that they got the first report of any casualties.

Collins’s body was first placed into the armored car, then transferred to the touring car for the sad trip back to Cork City. On the way into Cork City, Dalton stopped the convoy at a church in Cloughduv. Dalton asked where was the priest’s house? Getting directions there, they knocked on the door and the curate, Fr. Timothy Murphy, came to the railing. Seeing Collins was beyond hope, he turned to get the sacred oils, but Cmdt. O’Connell misunderstood this to be a refusal of his ministry. O’Connell pointed a pistol at him, but Dalton knocked it away.

As they approached Cork City they stopped at the Sacred Heart Mission at Victoria Cross. Here Fr. O’Brien administered the Last Rites to Collins.

Then the convoy headed back to the Imperial Hotel, where Dalton, Cmdt. O’Connell, Sgt. Cooney and Lt. Gough went into the Hotel to inform Maj. Gen. Dr. Leo Ahern and asked him to take charge of the body.

Dr. Ahern first examined Collins’s body when it was brought to the Imperial Hotel, and then at Shanakiel Hospital. He was the first doctor to examine the body and pronounced Collins dead. His examination found a large, gaping wound “to the right of the poll. There was no other wound. There was definitely no wound in the forehead.”

From the hotel, Collins’s body was taken to Shanakiel Hospital in Cork, where Dr. Michael Riordan was detailed by Dr. Ahern to examine and prepare the body, and they conducted the autopsy. Dr. Christy Kelly was present during a thorough second examination later and confirmed a huge wound on the right side behind the ear, with no exit wound. In contrast, Dr. Patrick Cagney, a British surgeon in the British army during the war who had a wide knowledge of gunshot wounds and who examined the body still later confirmed there was an entry wound as well as a large exit wound.

Eleanor Gordon, Matron of Shanakiel Hospital, and nurse Nora O’Donoghue cleaned and attended to Collins’s wounds and also later testified to the nature of the wounds. His body was first taken to room 201, then to room 121 after the autopsy where Free State soldiers guarded it until taken to the ship for transport to Dublin. In the afternoon, Cronin & Desmond Funeral Service performed their duties. Fr. Joseph Scannell, Army chaplain, and Fr. Joe Ahern recited the funeral prayers.

Michael Collins (Getty Images)

Back home to Dublin

The steamship SS Classic left Penrose Quay in Cork and brought Collins’s body from Cork to Dublin. General Dalton sent this handwritten telegram from the Cork GPO to the Dublin HQ:

CHIEF OF STAFF DUBLIN

COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF SHOT DEAD IN AMBUSH AT BEALNABLATH NEAR BANDON 6.30 [sic] TUESDAY EVENING WITH ME, ALSO ONE MAN WOUNDED. REMAINS LEAVING BY CLASSIC FOR DUBLIN TODAY WEDNESDAY NOON. ARRANGE TO MEET. REPLY DALTON.

As the vessel sailed down-channel from Cork, it passed the assembled remaining British vessels, upon the decks of which the British sailors mustered, saluted, and the Last Post played.

Michael Collins in October 1921 (Getty Images)

Read more

The Éamon De Valera factor

Though he was within a few miles of Béal na mBláth on the day Collins was killed, Éamon de Valera had hoped to meet him, but no plan had been made. Moreover, de Valera was not involved in the ambush; he had little political influence on the IRA at the time and no military influence at all. By this time, de Valera was trying to bring the Civil War to a halt, as well.

Liam Deasy spoke with de Valera the night before and de Valera’s position was that having made their protest in arms, and as they could not now hope to achieve a military success, the honorable course was for the IRA/Republicans to withdraw. Deasy explained that there were over a thousand men in the area and they would not agree to an unconditional ceasefire.

The next day, de Valera went to Long’s Pub, and his efforts at a ceasefire were rejected again. The most reliable evidence indicates when de Valera went to Long’s Pub he also tried to prevent the ambush but was rebuffed by the IRA/Republicans. Liam Lynch, O/C of the IRA in the south-west, specifically had given orders that de Valera’s efforts to cease hostilities should not be encouraged.

Again, Deasy met with de Valera and explained to him that the men billeted in this area would consider Collins’s convoy as a challenge that they could not refuse to meet.

Despite rumor and innuendo, there is no evidence that de Valera was involved in the planning or the ambush being laid for Collins.

Later de Valera was quoted: “A pity. What a pity I didn’t meet him.” And “It would be bad if anything happens to Collins, his place will be taken by weaker men.”

Harry Boland, Michael Collins, Eamon de Valera, and Eamon Duggan in February 1922 (Getty Images)

The funeral of Michael Collins

On the morning of August 23, Richard Mulcahy, as Free State Army Chief of Staff, issued the following message to the Army:

“Stand calmly by your posts. Bend bravely and undaunted to your task. Let no cruel act of reprisal blemish your bright honor. Every dark hour that Collins met since 1916 seemed but to steel that bright strength of his and temper his brave gaiety You are left as inheritors of that strength and bravery. To each of you falls his unfinished work. No darkness in the hour: loss of comrades will daunt you in it. Ireland! The Army serves—strengthened by its sorrow.”

Michael’s sister, Hannie Collins, with whom he lived when he first went to London in 1906, had long planned a holiday to Ireland in August. On the morning of August 23, she went to work at the post office in West Kensington. As she was about to enter her office she was stopped, taken into the superintendent’s room, and told there was a rumor that her brother had been killed. She said she was not surprised—during the night she had had a premonition he had been killed. “I know how unhappy he had been for so long—At the moment of death the load went…from his mind, so it went from mine.”

She went to see her friends, John and Hazel Lavery, but they were not home, so she went to board the Irish boat train at Euston Station. (The Laverys had already gone to Ireland where Sir John was painting.) Winston Churchill, having been told of Hannie’s distress by the Laverys’ butler, reserved a compartment for her and paid her travelling expenses. A newspaper reporter at Euston recorded that “Miss Collins, dressed from head to foot in black, was seen off by a lady friend. She was a calm but pathetic figure. She traveled alone.”

George Bernard Shaw wrote to Hannie:

“Don’t let them make you miserable about it: how could a born soldier die better than at the victorious end of a good fight, falling to the shot of another Irishman—a damned fool but all the same an Irishman who thought he was fighting for Ireland—‘a Roman to a Roman’…I met Michael for the first and last time on Saturday last, and I am very glad I did. I rejoice in his memory and will not be so disloyal to it as to snivel over his valiant death.

“So, tear up your mourning and hang up your brightest colors in his honor; and let us all praise God that he had not to die in a snuffy bed of a trumpery cough, weakened by age, and saddened by the disappointments that would have attended his work had he lived.”

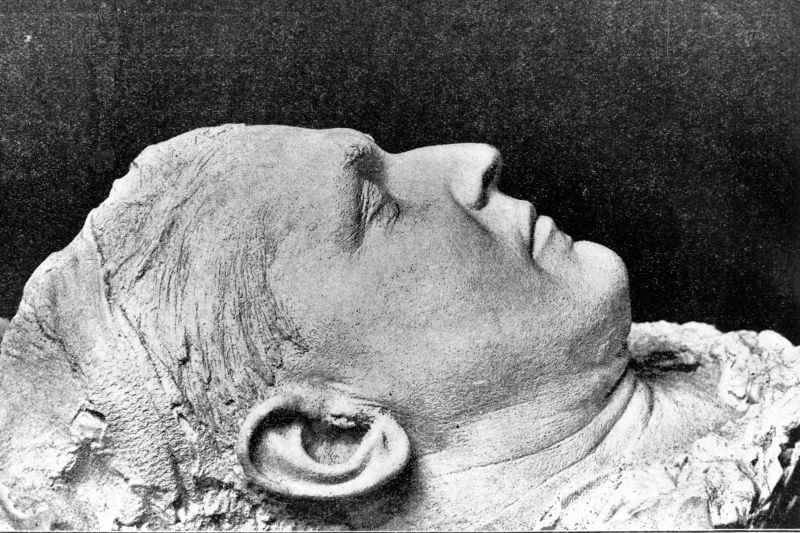

In Dublin, Collins’s remains were taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital where Dr. Oliver St John Gogarty embalmed the body and had Sir John Lavery paint Collins’s portrait. Albert Power sculpted the death mask.

The death mask of Michael Collins (Getty Images)

Collins’s body was taken to the chapel in St. Vincent’s on Thursday, August 24, then in late evening to Dublin City Hall for the public lying-in-state until Sunday evening.

Michael Collins laying in state in Dublin (Getty Images)

On Sunday evening, his body was removed to the Pro-Cathedral where it remained under guard overnight. His funeral Mass was said in the Pro-Cathedral on Monday, with Dr. Michael Fogarty, Bishop of Killaloe, the principal celebrant assisted by several other Bishops.

The gun carriage on which the casket was transported to Glasnevin Cemetery had been borrowed from the British and used in the bombardment of the Four Courts in June. The Free State Government specially purchased four black artillery horses from the British to pull the caisson to Glasnevin.

The funeral procession for Michael Collins (Getty Images)

Collins’s death was never officially registered, there was no inquest, and there was no formal, independent autopsy. When the Fianna Fáil government was to take over in 1932, it was said that many papers relating to Collins’s killing were taken from Portobello Barracks and burned by the order of the Minister for Defense, Desmond FitzGerald.

Collins died intestate, leaving an estate of £1,950.9s.11d, which passed to his brother Johnny.

Michael's brother Sean Collins at Michael's coffin (Getty Images)

Praise for the fallen Michael Collins

The British press acknowledged Collins’s part in the struggle for Irish freedom. The Daily Chronicle called him a “young and brilliant leader.” The Evening Press described his death as a “staggering blow.”

The Daily Telegraph wrote: “He was a bitter and implacable enemy of England while the English garrison remained in Ireland and Ireland was not free to govern itself in its own way. …The dead man, without a doubt, was the stuff of which all great men are made.”

The London Daily Sketch editorialized: “The hand that struck down Collins, guided by a blinded patriotism, has aimed a blow at the unity of Ireland for which every one of her sons is fighting. Collins was probably the most skilled artisan of the fabric of a happier Ireland. Certainly, he was the most picturesque figure in the struggle; and in the rearing of a new State a popular ideal serves as the rallying point to draw the contending elements. The death of Collins leaves the ship of the Free State without a helmsman.

“Other sons of Ireland have risen from lowliness to eminence in the struggle, but Michael Collins, by his valor, his sufferings, his elusiveness during the more turbulent periods of the past, and by his own personal charm, bound a spell round the popular imagination and wove a romance which endeared him to his friends and inspired respect in his foes.

“Since the historic hour in the early morning of December 6…the progress of the new State has been dogged and delayed by a malignant Fate.

“The next phase in the life of the Free State is veiled by the tragedy of the present. The helmsman has gone at a moment when no haven can yet be decried.

“What is to happen now?”

Seven years later, Winston Churchill would pay homage to his one-time military enemy and political ally. He admired Collins but evidently continued to be ignorant of the ideals that had driven and permanently separated the two men: “He was an Irish patriot, true and fearless. His narrow upbringing and his whole life had filled him with hatred for England. His hands had touched directly the springs of terrible deeds. We hunted him for his life, and he had slipped half a dozen times through steel claws. But now he had no hatred of England.”

Shane Leslie wrote the following lines:

What is that curling flower of wonder

As white as snow, as red as blood?

When Death goes by in flame and thunder

And rips the beauty from the bud.

They left his blossom white and slender

Beneath Glasnevin’s shaking sod;

His spirit passed like sunset splendor

Unto the dead Fianna’s God.

Good luck be with you, Collins,

Or stay or go you far away;

Or stay you with the folk of fairy,

Or come with ghosts another day.

Brendan Behan’s mother, Kathleen, nicknamed Michael Collins her “Laughing Boy.” She and her first husband had both served in the Rising. In 1935, when he was twelve years old, Brendan wrote a lament to the “Laughing Boy:”

T’was on an August morning, all in the dawning hours,

I went to take the warming air, all in the Mouth of Flowers,

And there I saw a maiden, and mournful was her cry,

‘Ah what will mend my broken heart, I’ve lost my Laughing Boy.

So strong, so wild and brave he was, I’ll mourn his loss too sore,

When thinking that I’ll hear the laugh or springing step no more.

Ah, cure the times and sad the loss my heart to crucify,

That an Irish son with a rebel gun shot down my Laughing Boy.

Oh, had he died by Pearse’s side or in the GPO,

Killed by an English bullet from the rifle of the foe,

Or forcibly fed with Ashe lay dead in the dungeons of Mountjoy,

I’d have cried with pride for the way he died, my own dear Laughing Boy.

My princely love, can ageless love do more than tell to you,

Go raibh maith agat for all you tried to do,

For all you did, and would have done, my enemies to destroy,

I’ll mourn your name and praise your fame, forever, my Laughing Boy.

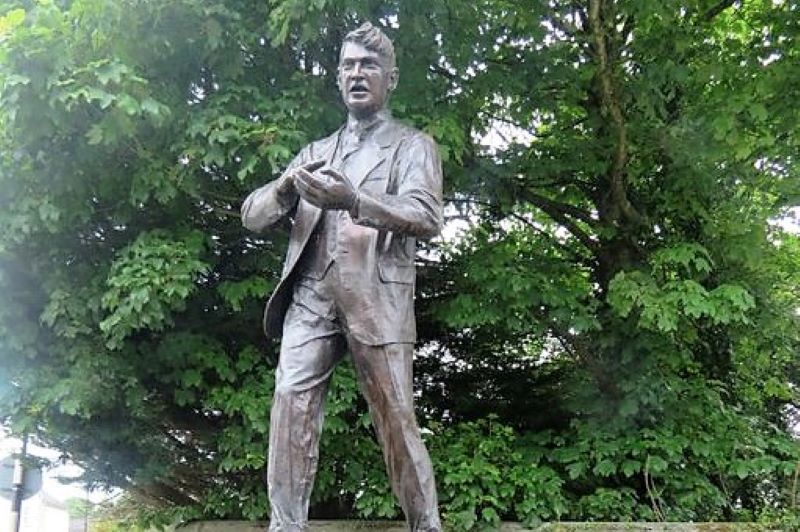

A statue of Michael Collins in Co Cork (Ireland's Content Pool)

*Originally published in August 2018, updated August 2025.

*Joe Connell served in the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, the NFL, and received a degree from Pepperdine University School of Law. His interest in Ireland, and particularly in its history, reflects his Irish heritage. In time he came to concentrate his research/interest on early 20th century Ireland—with a focus on the period prior to the Easter Rising up to the founding and early days of the Irish Free State. He is the author of the eponymous Dublin in Rebellion, Dublin Rising 1916, Who’s Who in the Dublin Rising 1916 and his most recent book, Michael Collins, Dublin 1916-1923. Connell is a columnist in History Ireland and has written several books for Kilmainham Tales. He is available to speak to groups in the U.S. and can be reached at [email protected].

Comments