In the final days of Michael Collins’s life, his movements through Munster reflected both a military leader’s urgency and a statesman’s hope for peace. From inspections at barracks and prisons to secret negotiations and attempts to reclaim Republican-held funds, Collins pursued stability amid chaos.

As Civil War tensions escalated and peace talks collapsed, a fateful journey through the Cork countryside ended in assassination, forever altering the course of Irish history.

20 August – Inspection tour and hopes for peace

Michael Collins embarked on another inspection tour, hopeful of a Republican conference in Clonmel. He visited the military barracks at Naas, the Curragh camp, and Maryborough (Portlaoise) Prison. After a visit to the prison, Collins travelled on to Limerick, where he conferred with Michael Brennan, and then proceeded to Mallow, where Commandant Tom Flood was in charge. (Frank Flood, Tom Flood’s brother, had been hanged by the British on 14 March 1921).

Collins had previously written to Sean O’Hegarty (Cork No.1 Brigade) to try to arrange a meeting, presumably to discuss peace. In his role as Minister of Finance, Collins was also very interested in securing the Customs and Excise taxes that Republicans had collected at gunpoint. They had sent several armed men to visit a Revenue official and forced him to put pen to paper and sign off for the funds (the money had been hidden in the bank accounts of Republican sympathizers).

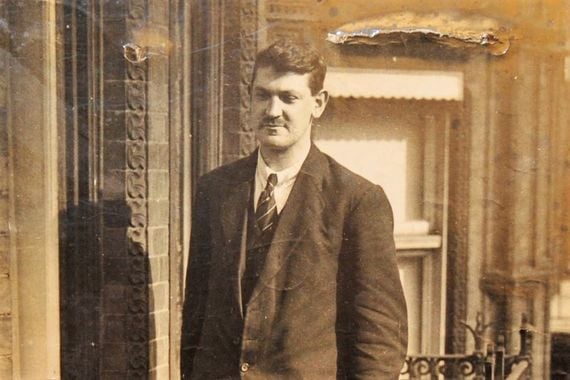

Michael Collins.

Collins was particularly “interested in the Childers’ bank accounts because he had an idea that the Republicans might be planning to buy arms abroad and to pay for them through this channel”.

The “Big Fellow” may have intended to collect these funds, reportedly more than £100,000, which some claim were with his party when he was shot but fate interjected in man’s scheduled affairs. Peace negotiations and collected tax deposits were all disrupted when death came calling at Béal na mBláth (see August 22).

21 August – Ambush at Clonmel and Republican movements

Collins had dispatched Frank Thornton to Clonmel to ascertain which side held the barracks and if their allegiance could be trusted. Thornton left Waterford at about 10 am in an open Ford car, accompanied by four other soldiers. (Meda Ryan, in her book The Day They Shot Michael Collins, claims that Thornton left Limerick shortly before Collins arrived).

Read more

They ran into a Republican ambush. Sgt. Finnegan and, by some accounts, Private Cantwell were killed, their bodies peppered with bullets from Lewis, Vickers, and Thompson guns.

Thornton was severely wounded, suffering bullets in his leg, arm, and back. The two other soldiers were taken prisoner by the IRA attackers and led off. The leader of the Anti-Treaty Party stopped a cyclist on the road and gave her a note to take to Clonmel, informing the National forces that several soldiers and a wounded officer were lying on the roadside.

A young doctor who had accompanied the attack party rendered first aid to Thornton. Some of the IRA were still at the scene when an ambulance arrived from Clonmel to collect Thornton and the two dead troopers. As they helped lift Thornton into the vehicle, one IRA man remarked that “Colonel Thornton was a good and brave soldier, one of the best I have ever met.”

Thus, the Clonmel negotiations never came to be.

As an executive meeting was scheduled for the next day, other officers of the Executive Forces stayed that night at the home of Mr. John Long at Béal na mBláth.

Tom Hales was one of them. It can be surmised that other important IRA officers were housed nearby. Liam Deasy drove de Valera through the Béal na mBláth valley the next morning (22 August).

A local girl, Maggie Long, well remembers having to serve a 2 p.m. lunch to the “Long Fella,” who was disguised in clerical garb. On the evening of the 22nd, Republicans gathered in Tom Murray’s house, de Valera among them.

Mrs. Shorten remembers his being dressed as a priest! “She should know─she gave him dinner, with my [Tom Murray’s] mother” (The Dark Secret of Béal na mBláth by Patrick J. Twohig, pp. 80−81, 232, 234, 235, 237).

Meda Ryan, on the other hand, in her book The Day Michael Collins Was Shot, claims that de Valera was at the morning meeting in Murray’s farmhouse but left before the ambush was set up.

“With his aide, Jimmy Flynn, he took the Cloughduv and minor roads [bypassing Cork city] and on to Mourne Abbey near Mallow”.

Clearly, the two versions do not match up

22 August – Final meetings and the fatal ambush

Collins met Florrie O’Donoghue the afternoon/evening of 21 August and the morning of 22 August in Macroom. O’Donoghue was a neutral member of the IRA but also acted as a liaison between the two sides.

What discussion took place at those meetings can only be surmised. Collins left for his inspection tour that took him on toward Bandon, where he was cautioned by newly-arrived Commandant Sean Hales, also a member of the Dáil, that safe passage was not secure for so skimpy an escort party through bandit country but Collins was not dissuaded.

Meanwhile, at 11 am, Denny Coveney, Tom Foley, and Tadhg O’Sullivan set out from Béal na mBláth headed for Newcestown, where two of the three mines to be used in the ambush were stored.

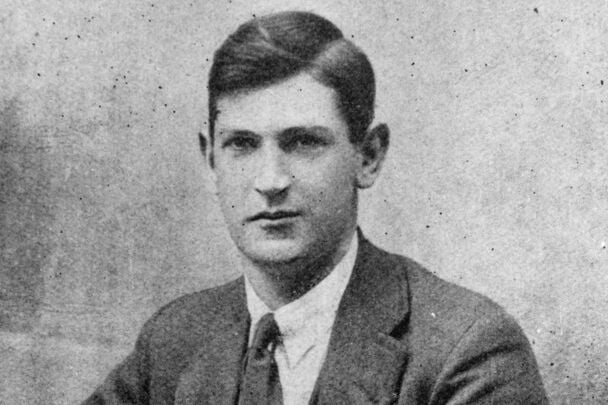

Michael Collins.

The three men brought back the large and small mine and took them to Liam Deasy. The “large landmine was sunk in the main road at Glanarouge bridge and slightly on the Béalnabláth side of it.”

The smaller one was sunk “in the surface of the by-road just across the bridge.” A third mine, which had been made elsewhere, was placed in front of the horse-cart barricade, about one hundred and eighty yards from the bridge (Tom Foley in The Dark Secret of BéalnamBláth by Patrick J. Twohig, pp. 242−243).

The barricade was a simple one, a dray from the brewery in Bandon that came every Tuesday to the local pub. The horse was taken away, and the wheels were removed from the cart. Liam Deasy had placed a Lewis gun on “The Rock,” which was located about 30 feet above the road and provided a commanding view of the landscape from bridge to barricade.

Read more

The ambush was manned by a large number of Cork Republicans (Deasy later stated about 25, others said 40). The ambushers were lined up along the fence of the old roadway. The battle did not take place where it was originally intended. Michael Collins was shot forty yards distant from the site of the present-day monument. The memorial was placed in its present position for convenience, not for historical accuracy.

All the men knew that Collins’s convoy had travelled this route earlier in the day, and they fully expected the convoy to return through the “Mouth of the Flowers.” But as dusk descended, the men began to abandon their positions, tired from a day-long vigil, disappointed that no vehicles had come into their gun sights.

John O’Callaghan dismantled two of the mines, and most of the men were heading up to Murphy’s place when they heard the rumble of motor-cars.

Only six men were near enough to return to the ambush site. Others, however, had by chance converged on the scene. A band of Kerry men who had been off fighting in Cork city were walking the fields, headed for home, when they heard the sound of gunfire along the valley southwards.

They ran about a half mile to the scene, which brought them to a little plateau eighty feet above the ambush site. Jimmy Ormond of Waterford was with another band of men several fields away when they heard the crack of rifle fire and hastened to the centre of action.

The following are the names of the men known to have been near or on site at the time that Collins fell:

- Dinny Brien

- Pat Buttimer

- Tom Crofts

- Liam Deasy

- Robert “Bobs” Doherty

- Mike Donoghue

- Charlie Foley

- Tom Foley

- Shawno Galvin

- Tom Hales

- James “Tod” Healy

- Dan Holland

- Jim Hurley

- Jim Kearney

- Pete Kearney

- Tom Kelleher

- Denny “The Dane” Long

- John Lordan

- (Perhaps) Mick Lynch

- Joe Murphy

- Mick Murphy

- John “John Mac” McGillicuddy

- John O’Callaghan

- Dan O’Connor

- Denis “Sonny” O’Neill

- Ted O’Sullivan

- Tim O’Sullivan

- Jimmy Ormond

- Bill Powell

- (Perhaps) Con Quill

- Pat Riordan

Aftermath – Confusion, escape, and a bloodied return

The circuitous route taken by the escort party when returning to Cork city with Collins’s body can confound the modern reader. Several things hindered a direct beeline to safety.

Many of the bridges in the area had been demolished by the Republicans to halt the progress of national troops who had landed on the coasts. The touring car in which Collins was placed was a dinosaur unto itself. The Leyland Thomas was one of only 18 ever built and had been designed to rival Rolls-Royce in style and mechanical sophistication. (Collins had acquired it from General Nevil Macready in the transfer of power when the British left Ireland.) Who knew how to drive it? It had an unusual starting mechanism and was quite heavy, considering it was sometimes relegated to the fields, where it usually got mired.

The convoy carrying Collins’s body wove a curvy path through Cloughduv, where the priest’s housekeeper, Annie White, bandaged his head with a liturgical linen towel.

After asking directions to Cork, the army officers were told that Aherla village was only two miles farther. Instead of following the directions, the convoy swerved into an avenue half a mile farther on that led to Annesgrove House, where Collins’s body was brought into the stone-flagged kitchen so that the blood could be wiped from his face.

Returning to the convoy, the soldiers made their way to the Cork-Macroom railway line, carefully negotiated the narrow wooden bridge over the Bride River, and arrived at the main Macroom to Cork road. The convoy went up to the Ovens bridge, which they found destroyed and the road to Kilumney blocked off.

They had to retrace their steps. Resting at the Magner and O’Sullivan farms, the officers scoured the adjoining fields looking for a way to the Ovens church and beyond to the road leading to Kilumney. The rank and file went into both farmhouses “and made themselves comfortable” while the body of Collins was left on the roadside with no one on guard (The Dark Secret of Béal na bláth by Patrick Twohig, p. 167).

An officer (probably Sean O’Connell) came roaring into the farmhouse and ordered the men out. The convoy again proceeded over the field and path until the armoured car, Slievenamon, got stuck in Cal McCarthy’s field and had to be abandoned. Collins’s body was then transferred to one of the other vehicles.

Read more

The local farmhand, O’Halloran, guided the convoy as far as Grange Cross “from where they continued on the back road, south of Ballincollig, to Dennehy’s Cross in Cork City, and so on to the Western Road” (The Dark Secret of Béalnabláth by Patrick Twohig, p. 171).

Collins’s body was taken to Shanakiel Hospital, where it received a cursory autopsy, incomplete by any modern standards. That night, when news of Collins’s demise reached the Republican prisoners in Kilmainham Gaol, after the initial shock of silence, nearly a thousand men knelt down and recited the Rosary for the soul of the man they had been fighting against.

Tom Barry, one of the prisoners, later remarked, “I have yet to learn of a better tribute to the part played by any man in the struggle with the English for Irish independence.” (Michael Collins and the Brotherhood by Vincent MacDowell, p. 146)

Future reading

- "The Day Michael Collins Was Shot" by Meda Ryan

- "Green Against Green" by Michael Hopkinson

- "The Dark Secret of Béalnabláth" by Patrick Twohig

- "Michael Collins" by Tim Pat Coogan

- "The Men Will Talk to Me: Kerry Interviews" by Ernie O’Malley, edited by Tim Horgan and Cormac O’Malley

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments