Though in the throws of "The War to End All Wars", the First World War, troops from both sides stopped fighting and enjoyed a few hours of peace in the trenches in 1914.

My grandfather, Peter Farrell of Drumconrath, County Meath, like many thousands of Irishmen joined the British army and fought in the Great War. Despite being offered a scholarship he decided on a life of adventure and signed up in 1907. He had completed a four-year tour of duty with the 2nd Battalion Leinster regiment in India when the regiment returned to County Cork where he would become a regimental piper.

The regiment was under canvas, in Moore Park, Fermoy, at the end of July 1914, when news arrived by motorcyclist of the imminent outbreak of war. Political tension was almost at breaking point. Austria was already at war with Serbia. Belgium and Russia were mobilizing, Germany had sent troops to the frontier, and Britain had dispatched her navy to sea whilst its troops were held in a state of readiness.

As the tension mounted on Aug 1, Germany declared war on Russia. By refusing to respect Belgian neutrality, France was forced into a general mobilization. The following day, having violated the neutrality of Luxembourg, the German army massed at the Belgian border and on August 3 marched across the frontier.

On Aug 4, following an ultimatum issued via the British ambassador in Berlin requesting that Belgian neutrality be respected and having received no response, Britain and Germany were now at war.

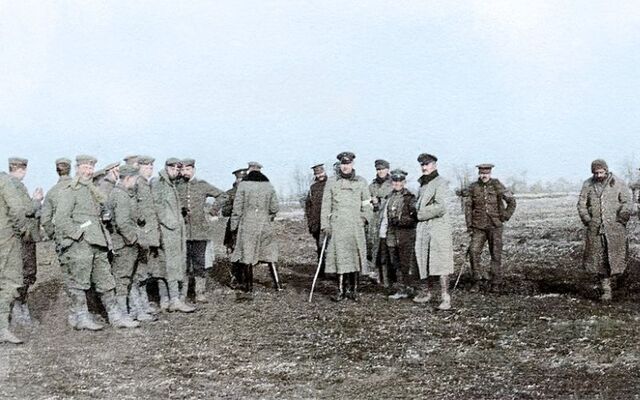

Soldiers in the trenches during World War One.

The 2nd battalion was described by the Battalion Captain, Francis Hitchcock, as a fine body of men; physically impressive with an average height of 5 feet 10 ins, which when considering the average ‘Tommy’ was about 5 feet five ins they must have seemed like giants. For infantrymen, height was not necessarily an advantage.

Captain Hitchcock recalls an incident in 1916 when the Leinsters relieved a Bantam battalion of undersized recruits at Guillemont:

“We spent the night deepening the trench and building up the parapets.’ What cover suited the Bantams of 4 feet 8 inches did not suit the 2nd Leinsters, averaging 5 feet 10 ins!”

On Nov 18, 1914, the 2nd Leinsters relieved the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in the trenches northeast of Armentieres. The conditions would prove to be in sharp contrast with their previous billet which ironically was the lunatic asylum in Armentieres where at least the men could experience the relative comfort of a large dry building with kitchens and baths. The distance from the German line varied between 200 and 500 yards and was occupied by the XIXth Saxon Corps.

The battalion immediately set to work on the seemingly Sisyphean task of trench maintenance.

“The conditions of trench life at the time were of extreme misery; parts of the trenches were continuously under water ;the unceasing labor of trying to keep the trenches from falling in had begun to tell on the ranks ;there was the never ceasing sniping on the part of the enemy while the venomous condition of the men was sapping their health. The misery of those December days of 1914 with, cold, wet ,mud and lice were perhaps never equaled throughout the war”.

So, wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Ernest Whitton, military historian.

On the evening of Dec 24 reports were filtering back to the company headquarters that the enemy had been seen hoisting Chinese lanterns on the parapets of their trenches and that although the sentries had promptly shot them to pieces, the Germans had started to shout over at the Leinster sentries requesting a cease-fire. The Leinster officers emerged from their shelter and could clearly hear the following appeal delivered in fluent English from the German line:

Play the Game! Play the Game!

If you don’t shoot. We won’t shoot!

If you don’t shoot. We won’t shoot!

The immediate response from the Leinster command was"

”That all haphazard sniping should cease, but that fire was to be opened at once upon any German seen approaching our lines.”

The night was reported as being “ uncannily quiet” with the Leinsters' capitalizing on the cessation of sniping by doubling their work rate on trench maintenance.

Read more

Following the Christmas Day ‘stand to’ at dawn, the soldiers resumed their duties in the trenches. The mutual cessation of fire was still being respected and all was quiet until quite incredibly, a party of unarmed Germans suddenly appeared in no man’s land bearing shovels, walking towards the Leinster line in broad daylight.

The work party proceeded to gather up the putrefying bodies of their dead comrades and bury them. Instinctively some Leinsters responded by leaving their trench to assist in the operation and to bury their own dead. They were soon joined by other unarmed Germans and within minutes a group of some 30 Irishmen and Germans had formed and were wishing each other “A Merry Christmas“ and were exchanging souvenirs; buttons, badges and coins and gifts; plum puddings and cognac. Quite a few of the Germans spoke English fluently, having worked in London before the war and were convinced that Ireland was at war with Britain.

Both parties returned to their respective trenches at 1 pm and enjoyed a peaceful Christmas lunch. News soon spread of similar incidences occurring along the front, instilling the men, perhaps with the hope of a more permanent end to the madness. The cease-fire lasted into January of the next year with the Leinsters reportedly being the last to resume hostilities.

My grandfather would see another two Christmases at the front before receiving a devasting head wound in September 1917. He would, however, survive, returning to County Meath where he would marry and pursue his love of music - teaching local people.

During the civil war in the time known locally as the ‘Tan War’ he would offer his assistance in training members of the IRA. The Black and Tans were frequent visitors to the village and local area and he would, according to family history, use his bagpipes as an early warning signal of the imminent arrival of their dreaded flying columns.

Consequently, his involvement would lead to the forfeiture of his army pension and a very bleak time ahead for a rural family in Ireland between the wars. After the Second World War in the 50s and 60s, My grandparent’s cottage in Drumconrath was well known as a ‘Celidh house’ and as a musical focal point, would become a nucleus for aspiring players including my Uncles Jodie and Colm who along with accordionist and singer Dermot O’Brien would form the Emerald Ceilidh band.

Read more

* This article was originally published in 2018 and updated in Dec 2024.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments