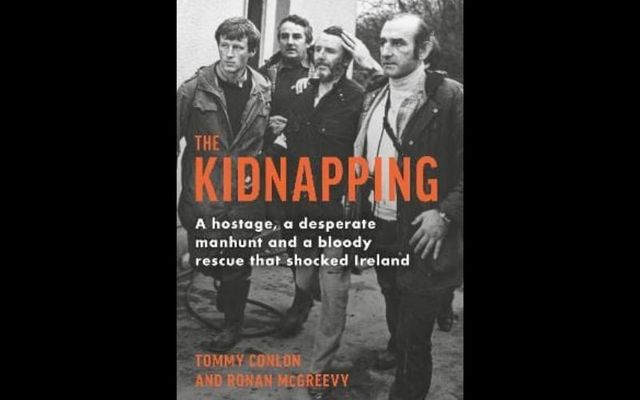

The following is an excerpt from "The Kidnapping: A hostage, a desperate manhunt and a bloody rescue that shocked Ireland" by Tommy Conlon and Ronan McGreevy:

The United States was a primary source of finance and weapons for the Provisional IRA in the first decade of the Troubles. By the early 1980s, however, US authorities were coming under pressure from the British and Irish governments to stem the flow of weaponry and money across the Atlantic.

Simultaneously there was a propaganda battle for the hearts and wallets of Irish America. Antipathy towards all things British was ingrained in generations of those with Irish ancestry.

One former official on the State Department’s Irish desk told the Washington Post at the time: “Most Americans simply do not know what goes on over there. What Noraid (Irish Northern Aid Committee) North America contributors know about Ireland seems to derive from hazy folk memories of the potato famine and the brutality of the British during the 1919 revolution.”

The US federal government responded to the entreaties of both governments by establishing an FBI squad in May 1980 to target the IRA in America. Over the following two years this unit set up a sting operation targeting an arms network run by George Harrison, the IRA’s main gun smuggler. Harrison was a U.S. combat veteran of the Pacific theatre in the Second World War.

According to some accounts he sent across 2,500 guns and large quantities of ammunition and explosives in the first decade of the Troubles. The IRA army council believed a more ambitious plan was needed and mandated Belfast man Gabriel ‘Skinny Legs’ Megahey to procure heavier weaponry for the IRA. Megahey embarked on the project, blissfully innocent that the FBI was watching his every move.

In June 1982 the Feds broke up a dual operation in New Orleans and New York which included the attempted purchase of five surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) capable of bringing down British army helicopters.

Such weaponry would have made parts of Northern Ireland, particularly south Armagh, no-go areas for British armed forces as helicopters were vital to their operations in places where they could not travel safely by land.

“We felt that if we could nullify the (British) helicopter, we would be well on our way to winning the war,” Megahey would later recount.

“Taking out British army helicopters would have worked wonders for morale and boosted our ability to prosecute the war on a wider level. It would also have had a corresponding effect on the British, not just operationally but in terms of undermining their morale and weakening their resolve.”

In his eagerness to obtain this weaponry, however, Megahey walked straight into the FBI’s sting operation at a hotel in Manhattan. He told a man he believed to be an armed dealer that he had $1 million to spend on weaponry. The man was an undercover agent. Megahey and three others were arrested and given jail sentences ranging between three and seven years.

“It was better than sex,” boasted FBI agent Lou Stephens, who was in charge of the operation. “Three times better. We really saved a lot of lives.”

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

It was the second significant setback for the Provisional IRA in North America.

Noraid founder Michael Flannery had been arrested in 1981 and charged alongside four accomplices with gun-running. Though they were eventually acquitted on the basis of entrapment in 1982, the trial brought unwanted attention on Noraid and on its links with PIRA.

These American reversals made the Republic of Ireland an even more important source of money and arms. The Republic had been a lucrative source of revenue through bank, post office and wages robberies, but these operations were becoming increasingly difficult and risked confrontations with the Irish security forces.

Armed escorts for bank cash deliveries were introduced in the early 1980s along with panic buttons, security screens and CCTV. The number of bank robberies in the Republic halved between 1981 and 1982 and plummeted to just seven in 1983.

Yet the Provisional IRA had an escalating need for money as its political wing, Sinn Féin, moved deeper into electoral politics following the election of hunger striker Bobby Sands in 1981.

The IRA’s southern command was tasked with meeting that need by whatever means possible.

Unknown to them, there was also an informer within their ranks. Kerry-born Seán O’Callaghan had joined the IRA at the age of seventeen and killed a Catholic RUC officer in 1974, but then turned against the organization.

At the time of the [Don] Tidey kidnapping he was acting as a double agent, informing the gardaí about planned IRA operations in the Republic. In 1998, after spending many years in jail, he published a book entitled The Informer: The True Story of One Man’s War on Terrorism.

According to O’Callaghan, the southern command was berated at a meeting in Midleton, Co. Cork, in late 1982 for its failure to raise enough cash. “The IRA was hovering on the brink of bankruptcy,” he recalled. “It had no money to expand. The row arose because there was a feeling that the southern command was failing to provide the IRA with the kind of money it expected. It was felt they would need an extraordinary intervention if they were to raise that kind of money.”

This would be the motivation behind their disastrous kidnapping strategy in 1983 which began with the abduction of Shergar, the Derby winner turned valuable breeding stallion, from Ballymany Stud in Co Kildare on February 8th of that year.

The IRA demanded a £2 million ransom from his owner the Aga Khan, but the kidnap gang could not manage this highly-strung thoroughbred and machined-gunned the unfortunate animal to death after it broke a fetlock in the horse box.

On August 8th, 1983 the IRA attempted to kidnap the Anglo-Canadian businessman Galen Weston from his Irish home in Roundwood, Co Wicklow.

The gang that arrived on a sunny Sunday morning had no idea that their plot had been rumbled well in advance by Garda intelligence. A crew of armed detectives was lying in wait. A gun battle ensued; five IRA men were wounded and later given long prison sentences. The plan to kidnap Tidey, therefore, was the triumph of hope over experience.

The British-born businessman ran the Weston family operations in Ireland, which included the Republic’s largest supermarket chain, Quinnsworth, the Stewart’s chain in Northern Ireland and a new emerging retail operation, Penneys.

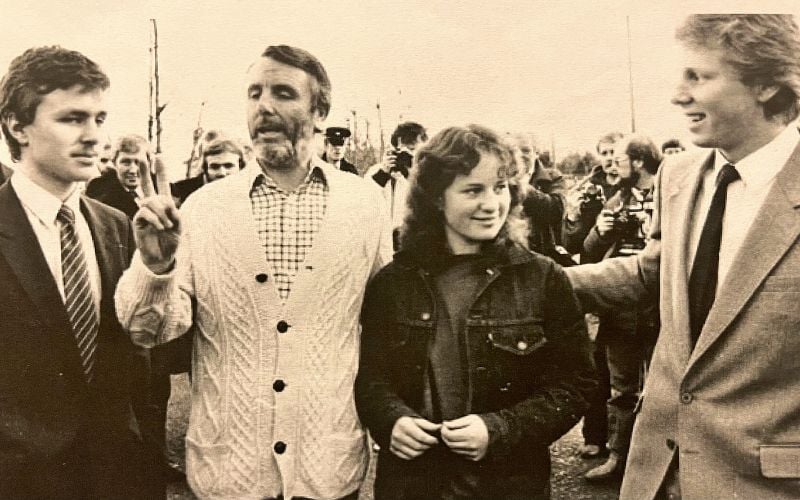

Tidey, then 48 and a widower with three children, was seized outside his home in south Dublin on November 24th 1983 and brought to Derrada Wood, about five miles outside Ballinamore in Co Leitrim, where he was kept for the next 23 days.

The IRA demanded £5 million from the Weston family firm, Associated British Foods (ABF), enough money to fund all its operations for two years. The abduction was an existential challenge to an Irish state which was struggling to keep law and order at a time of a severe economic downturn and record unemployment.

The kidnapping of a prominent businessman would do nothing to attract the foreign direct investment that the Republic so desperately needed to revitalise its economy.

The British government was no less resolute in its desire that the money not be paid. “I need hardly say that I feel as strong as you that it is vital that a ransom should not be paid in a kidnapping case. The apparent involvement of terrorists in this case adds to our resolve,” the British prime minister Margaret Thatcher wrote to her Irish counterpart, Garret FitzGerald.

The Tidey manhunt was the largest in the history of the Irish State with thousands of gardai and Irish army personnel involved. Well-known informers Sean O’Callaghan and another IRA insider turned tout, the notorious Freddie Scappaticci, had pinpointed Leitrim as the location of gang and captive.

Surveillance of prominent republicans in the county eventually brought the security forces to the lair in Derrada Wood.

On December 16th, a search party rescued Tidey, but in the process one member of the gang shot dead Private Patrick Kelly, a father-of-four from Moate, Co Westmeath, and a recruit garda, Gary Sheehan from Monaghan.

Their deaths provoked a national outcry and a backlash against the IRA and Sinn Féin in the Republicon a scale not seen before. The outrage at the murder of a garda and soldier was compounded by the actions of the IRA a day later when it detonated two car bombs outside Harrods in London, killing six people.

The four or perhaps five kidnappers escaped from Leitrim and two of them, tracked down five days later to a house in Claremorris, Co Mayo, escaped a second time. They had gotten away with murder and continue to do so to this day.

The operation was a qualified success. Don Tidey was freed and no ransom was paid, but a terrible price was paid with the deaths of two men.

The Irish government might have hoped that this would be the end of the kidnap threat, but two years later it was forced to put through emergency legislation to stop the payment of a suspected £1.75 million ransom payment from ABF to the IRA through a bank in Navan.

The Sunday Times had published an exposé suggesting ABF had decided to pay the money to stave off potential future kidnappings against the advice of its own security consultants.

The money was discovered by a stroke of good luck in America. Early in 1984 the FBI came across accounts associated with the IRA while they were investigating money-laundering operations by the Italian mafia in Boston.

In May 1984 a Scotsman named David McCartney Jr went into the Bank of Ireland branch on Fifth Avenue in New York and withdrew a series of US dollar drafts equivalent of IR£1,750,866 from an account which had been opened just a fortnight previously. It was deposited in a Bank of Ireland branch in Navan, Co. Meath, in the name of David McCartney Sr.

Alan Clancy and McCartney Sr, both businessmen who had made fortunes in the United States, had collaborated on several ventures, but their attempts to avoid paying tax had brought them to the attention of the authorities.

The massive transactions in Bank of Ireland’s Fifth Avenue branch were red flags for the FBI. When the gardaí were alerted to suspicious activity on the bank account in Navan, the Irish government immediately introduced the emergency legislation allowing them to seize the money.

The Offences Against the State (Amendment) Act 1985 was rushed through the Dáil during a day and night sitting on February 19. The Irish Minister for Justice Michael Noonan warned that if the money fell into the hands of the IRA, “the consequences for human life on this island would be grave”.

Both McCartney and Clancy protested vehemently that the money was legitimate cash for a pork business but lost a High Court case as they couldn’t prove the source of the funds. Neither of their estates made a claim on the money after they died in the 1990s. It was eventually paid into State coffers in 2008, by which time it had accumulated with interest to the sum of €6 million.

*"The Kidnapping: a hostage, a desperate manhunt and a bloody rescue that shocked Ireland" by Tommy Conlon and Ronan McGreevy is published by Sandycove and can be purchased in bookstores and online from Kennys Bookshop, Galway.

Comments