Where does the Black and Irish identity stand in America?

African-American Lenwood Sloan was in his 20s before he learned why his father insisted he is nice to the lone elderly white man that lived at the end of their block. Little was he expecting to discover that his family had a secret – that the man was his great-grandfather.

“Why was it kept a secret?” Sloan asks of the intrigued crowd, gathered back in 2015 to hear him delve into the complex history between Irish-Americans and African-Americans at “Black-Irish Identities: A Symposium” at Glucksman Ireland House, New York.

When faced with the facts, the appearance of a white man in Sloan’s family tree does not seem all that surprising. People such as Barack Obama, Muhammad Ali, Eddie Murphy, Billie Holiday, and Beyonce all have traces of Irish DNA or Irish ancestors.

Read more

Thirty-eight percent of African-Americans have some percentage of Irish DNA, Sloan claims, and there is a history of intermarriage between the two communities in places such as New Orleans that dates back to a time when African-American men had a life expectancy of 14 years while Irish-American men lived to 31. In contrast, Sloan tells how African-American women had an average life expectancy of 36 while Irish women could only be expected to live to 18.

Out of necessity, he says, a system of placage was established in which African-American women were placed in the security of white Irish men, creating three to four generations of intermarriage.

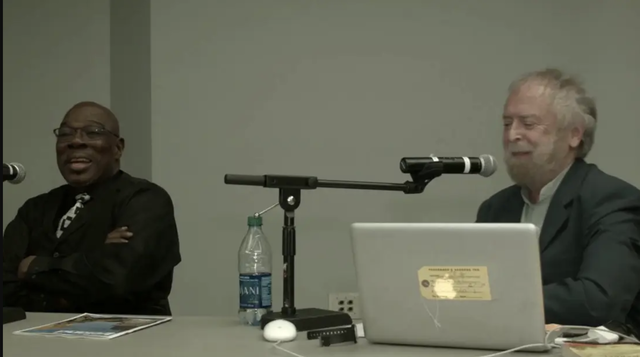

Speaking alongside musician and teacher Mick Moloney in a talk entitled “Two Roads Diverged,” Sloan, a cultural leader particularly interested in the subject of dance, explored the difficult relationship between two ethnic groups who both arrived to America at the bottom of the ladder.

Mick Moloney & Lenwood Sloan at USF [ 00-57-19-14] from k9sound on Vimeo.

Introducing the afternoon’s program, which also included a reading from Irish author Colum McCann and a performance from jazz group The Tara O’Grady Trio, Professor John Waters spoke of the “intersection of two cultures and two traditions” that has played a huge influence on American culture and how both groups have contributed to the other’s identity in the US, taking form in today’s Black Irish: “people of mixed race, of mixed history, and of shared history written into their bodies.”

The relationship between Irish-Americans and African-Americans has been strained and, particularly for Irish people, not always a source of pleasant memories of our or our ancestors' attitudes and actions.

The conflict, which often included violence shown by Irish people towards African-Americans, can be summed up in an anecdote told by singer Tara O’Grady: Although jazz aficionado Louis Armstrong was born and raised in an area of New Orleans where so much violence was seen it was known as “The Battlefield,” he was still scared to enter the nearby Irish neighborhood and with good reason. As urban legend tells it, Armstrong once asked an Irish cop for the time only to be hit over the head with the cop’s truncheon. “I’m glad it wasn’t 12 o’clock,” he is said to have quipped.

Both Irish and Africans were taken across the Atlantic – Africans as slaves and Irish as indentured servants, not quite slaves but with similar conditions and both treated as less than human, Moloney told the packed room.

At the bottom of the ladder, many Irish men lost their lives as they were placed first in the swamps, ahead of the slaves. “If a slave dies, you lose a price of property. If an Irishman dies, you can get another one,” was the general consensus.

The treatment the Irish endured brought out the worst in them as they fought their way out of the swamps towards paid jobs, often at the expense of slaves. Sloan tells of how Irish gangs would stone African-American laborers and nobody came to their defense.

Black/Irish relations hit an all-time low during Andrew Jackson’s term as US President, when the Irish were given permission to take land of freed slaves.

And yet, in later years, the plight of African-Americans and the discrimination they faced would be something that Irish people across the Atlantic could relate to, said author Colum McCann, following readings from his two books, “TransAtlantic” and “The Side of Brightness.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

“TransAtlantic” tells in part the story of African-American social reformer Frederick Douglass and his trip to Ireland in 1845/46. Douglass would later appear in murals in Belfast during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s as Catholics in Northern Ireland, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement in the US, took it upon themselves to fight for their equality.

McCann also read from “The Side of Brightness,” his novel about sandhogs digging tunnels under NYC, in which a marriage between an Irish woman and an African-American man plays a central part in the plot and deals with the complexities of this union, not just for themselves, but in further generations of their family. At one point in the novel, Eleanor denies that her son is hers in front of him and her co-workers so they would not know she was married to an African-American.

The identity of the Black Irish is also something that Tara O’Grady, who concluded the symposium events with a performance, chose to explore through her music. Born in Queens, of Irish ancestry and wearing a photo of Billie Holiday around her neck, O’Grady and her band (Michael Howell on guitar and David Shaich on bass) sing about Holiday’s Irish roots, Duke Wellington’s “Black and Tan Fantasy,” speakeasies in Harlem and create jazz-versions of Irish classics such as “Danny Boy.”

Irish and Irish-Americans often feel victimized and with good reason. Many times throughout our history we've been discriminated against and treated as the scum of the Earth – the lowest tier in society. "Black Irish Identities," however, questions the behavior of the Irish as they climbed up the societal rungs, looking down on those groups and communities below us.

Read more

Yes, we have played the part of the victim, but we've also played the part of the perpetrators of injustice.

Although we may not be proud of these lapses in moral and ethical behavior, coming away from this symposium you realize the importance of remembering and accepting our role in racial discrimination in the US so as to work towards righting our wrongs in the future.

For more information and further reading on the Black Irish or to share your story, you can visit: www.nyuirish.net/blackirish.

Are you a member of the Black Irish community or were you surprised to discover that you had Irish roots? We love to hear your stories, you can share in the comments section below.

*Originally published in 2015.

Comments