After traveling to Ireland, Irish American Joe Fahey is inspired to trace his family's roots.

In the weeks after I returned from Ireland with Meghan and Kate, I talked longingly of returning to it for a third visit. Terri, who had been very gracious about my taking the second trip with the girls six months after the first trip, told me I needed to take her to Italy first. In my book, that was more than fair.

Read More: Three tours to take on your next vacation in Ireland

Since we both were living busy professional lives, I was a judge in county court and she was the city attorney, we put our travel plans on the back burner.

Several years went by and one late weekend summer day in 2003, I was sitting in the sunroom at our home, giving a Mega Million lottery ticket a cursory glance while comparing the numbers on the ticket with the winning numbers published on the newspaper. It turned out that I had five out of six of the winning numbers plus the mega ball number. On Monday, Terri and I visited the lottery office and learned that the ticket was worth five thousand dollars.

“What are you going to do with the prize money?” Terri asked.

“I’m going to use it to get the Italy monkey off my back,” I replied, “let’s start making travel arrangement.”

Read More: American woman's search for her Irish roots pays off

We traveled to Italy during the last week of October that year and had a wonderful trip through Rome, Florence Luca, Siena, and Venice. Leaving Siena one morning, I looked in the rearview mirror and saw a scooter rider behind me. He was so close that only the goggles appeared in the mirror. I told Terri, “If I touch these brakes, he’ going to go over the top of the car and be in front of us.” I decided that I’d rather drive on the left side of the road in Ireland with the steering wheel on the right side of the car rather than our conventional way in Italy.

When we returned home, I still longed to return to Ireland, but it would be fifteen years more before I realized that dream.

In the intervening years, much occurred that would whet my appetite to do so.

I began to follow “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland and the Peace Process that was unfolding there. In particular, I studied the reports of the Independent Monitoring Commission which kept track of sectarian violence. I wrote an article titled “The Elusive Promise: Northern Ireland and the Quest for Peace” which I was invited to present at the regional conference of the American Conference of Irish Studies in Portland, Oregon.

I was approached by the local chapter of the Irish American Cultural Institute and asked to write a profile of my great-uncle, James K. McGuire, the youngest Mayor in the history of Syracuse, New York and leader of the Friends of Irish Freedom, a national organization that raised money for Irish independence in the years before, during and after the 1916 “Rising” in Ireland.

James K. McGuire (Library of Congress)

Read More: Remembering Eamon de Valera - a voice in Ireland's politics for over 50 years

I knew from family lore that Eamon DeValera fled to America after escaping jail in England that he had been sheltered by my ancestor, a fact that DeValera confirmed during a visit my parents had with him in 1973. My knowledge of McGuire was limited to what had been passed down from my mother, his niece, but I began to research his life and discovered a fascinating individual. When I was done, the profile amounted to thirty-eight pages on his life. The anthology was never completed or published.

I submitted the profile as a topic for the annual conference of the American Conference of Irish Studies to be held in New York City in April 2007 and was invited to present it on Friday, April 21 at City University of New York. Terri and I traveled to New York where I gave a talk entitled “James K. McGuire Boy Mayor and Irish Patriot.”

Shortly after I returned home, I was contacted by James Mackillop, who was the Editor of the Irish series at Syracuse University Press and very active in the American Conference of Irish Studies. He told me that he had been at the ACIS Conference in New York and had very favorable reviews of my talk. We met for lunch and he asked me if I thought I could turn the paper into a full-blown biography. I told him that I thought that I could without realizing that it would consume much of the next seven years of my life.

Read More: Trace your Irish roots using this Irish naming pattern

My great-uncle left no papers, letters, diaries or any other evidence concerning his experiences or thoughts about the events in his life. I was forced to go to a variety of sources, official mayoral correspondence, newspaper accounts, books that he published and the writings of others whose lives intersected with his fascinating journey through life. My research ultimately filled several large boxes which I would donate to the local historical society at the end of my quest to chronicle his life.

One of my earliest discoveries came from my great-grandfather’s obituary in the local Catholic newspaper. I discovered that my mother’s family didn’t come from Athlone but rather Enniskillen in Northern Ireland. My mother had passed away by then, but I delighted in calling all of my siblings who had made pilgrimages to Athlone and asking them, “Where is Mom’s family from?”

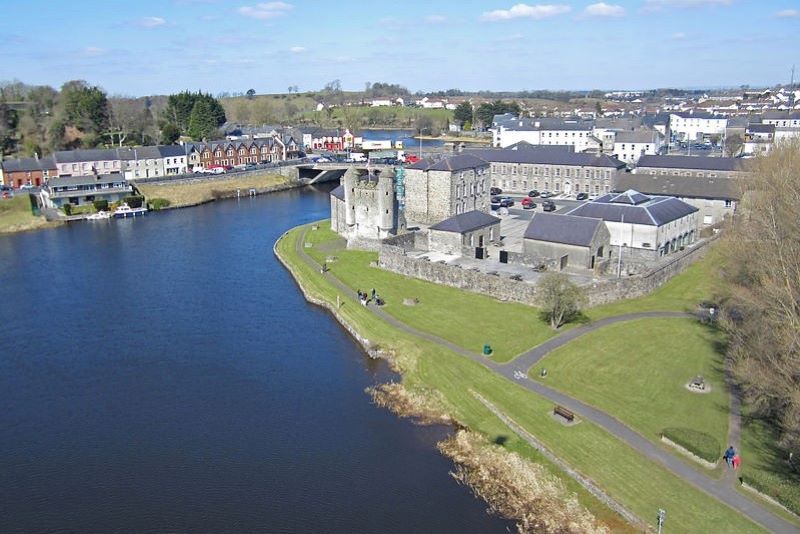

Enniskillen (Ireland's Content Pool)

“Athlone” they all answered, “we’ve all been there.”

“Well, I hate to break it to you, but I found her grandfather’s obituary in the Catholic Sun and it says that he’s from Enniskillen in Northern Ireland.”

My youngest sister, Jane, who never lacked certitude said, “Maybe it’s wrong.”

“You don’t think they knew where he was from when he died?” I replied, “he was only forty-nine years old.”

I continued to research and write about each episode in his life in local, state and national politics and his involvement in the 1916 “Rising” and fight for Irish independence. Along the way, I learned about fascinating characters from that era such as John Devoy, Michael Collins, Roger Casement, DeValera and a figure from an earlier era named Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, who is the subject of my current writing project.

De Valera (center) and Devoy (seated below), in 1920.

Read More: The New Year's Resolution Irish bucket list: Things to do in Ireland before you die

In 2013 I delivered the Manuscript entitled James K. McGuire: Boy Mayor and Irish Nationalist to Syracuse University Press. It was over nine-hundred pages. The editors at the Press persuaded me to cut it to slightly over three-hundred pages. It was published in 2014 and won the 2014 Central New York Book Award in Non-Fiction.

After the launch of the McGuire biography, I turned my attention to researching the life of O’Donovan Rossa. I followed the same routine of scouring the newspaper accounts about him both in Ireland and the United States. Fortunately, Rossa wrote his own recollections about the various episodes in his life and there is much great writing about the “potato famine” by the acclaimed Irish historian Tim Pat Coogan, Cecil Woodham-Smith and others although “famine” is a term that Rossa, Devoy and even James K. McGuire eschewed.

In 2015 I retired and had even more time to devote to this project and the desire to return to Ireland and make a long-overdue pilgrimage to Enniskillen to see where the McGuires came from as well as the many places I was learning about in my research was upon me again. I proposed the idea of a trip to Ireland to my close friend and law school classmate, Pat Doyle, a very successful lawyer in Washington, D.C. We agreed to meet in Dublin in August 2017 for a few days and travel throughout Northern Ireland.

More to come ...

Read More: New Year's Resolution: Get "unstuck" in your genealogical research

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments