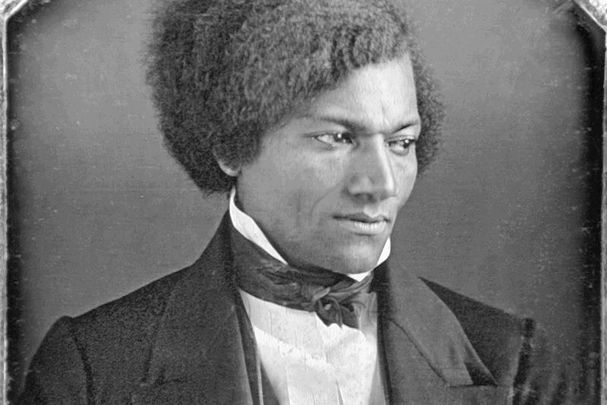

Frederick Douglass, who spent time traveling in Ireland, had plenty of opinions about the Irish.

There is a petition underway in Cork City to have a street named after former slave Frederick Douglass, the original 'Black Lives Matter’ advocate who spoke powerfully about his experiences as a slave and then as a free man and freedom fighter for all oppressed people.

Read More: Petition to rename Cork street after Frederick Douglass gains momentum

Douglass was a friend of both President Abraham Lincoln and Daniel 'The Liberator' O’Connell, and his impact during a lengthy visit to Ireland in 1845 at the onset of the Famine was extraordinary. Over four months, Douglass traveled to Dublin, Limerick, Belfast, and Cork, where today there's a statue to him at UCC.

While he is revered in Ireland, it's worth remembering that Douglass, like most of the anti-slavery activists at the time, was fervently anti-Catholic.

It is a strange conundrum. As Joan Walsh, the author of "What's the Matter With White People: Finding Our Way in the Next America," wrote in Salon magazine: “American abolitionists tended to be elite evangelical Protestants with grave doubts about the fitness of Irish Catholics for American democracy. The Beechers and the Tappans, Wendell Phillips, and Elijah Lovejoy; many of the renowned names of abolitionist history were also associated with ugly anti-Irish Catholic biases over the years.”

Douglass, as an associate of theirs, adopted the same high moral tone. He was also an Anglophile, thankful that the British had abolished slavery in 1807.

When it came to the causes of the Famine which he witnessed, Douglass was completely blind to any argument his beloved British were responsible for and blamed the drunken Irish instead.

In a letter to fellow abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, penned on February 26, 1846, Douglass wrote: “The immediate, and it may be the main cause of the extreme poverty and beggary in Ireland, is intemperance. This may be seen in the fact that most beggars drink whiskey…Drunkenness is still rife in Ireland. The temperance cause has done much—is doing much—but there is much more to do, and, as yet, comparatively few to do it.”

No doubt such trenchant statements were welcomed by the British and the abolitionists. The Irish were starving themselves, Douglass seemed to be saying, because of their mad lust for drink.

Read More: Frederick Douglass was quickly captivated by Daniel O'Connell in 1845 Ireland

Yet he was clearly ambivalent, given the massive reception he received everywhere in Ireland.

In an earlier letter to Garrison, this one penned from Belfast on January 1, 1846, Douglass said: “I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation, I live a new life.”

In Ireland, Douglass befriended Daniel O'Connell who had implored Irish Americans to seek to end slavery, but he took no position and stated as much on O’Connell’s effort to repeal the Act of Union of 1800 which had removed Ireland’s parliament. It appeared he did not want to offend the British in any way.

His anti-Catholicism came to the fore. On a trip to Rome, he described watching a procession of Catholic novitiates, saddened “that they are being trained to defend dogmas and superstitions contrary to the progress and enlightenment of the age.”

But he was also ferociously for human rights - “I am for fair play for the Irishman, the negro, the Chinaman, and or all men of whatever country or clime, and for allowing them to work out their own destiny without outside interference,” he wrote in an 18-page article entitled "Thoughts and Recollections of a Tour in Ireland."

Like all historical figures, Douglass was a complex mixture of an escaped slave, freedom fighter, and surprisingly anti-Catholic advocate. In today’s cancel culture, his diatribes against Catholicism might be enough to write him off, but the man in full soars far beyond any effort to stereotype him. He was fearless where it most counted, telling the story of his enslaved people.

Read More: How an Irish book tour transformed Frederick Douglass

Comments