Germany has long been quietly very grateful for Irish support on German unity when others were initially against it.

In the leafy setting of Farmleigh House in Dublin's Phoenix Park, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel has once again expressed her robust support for Ireland's position on Brexit and specifically on the issue of no return to a hard border in Ireland.

It was in an appropriate setting.

Farmleigh House, now owned by the Irish Government, was once the home of Lord Moyne, the Guinness-owning peer, who was sent to Palestine as a colonial peace envoy in 1944. He was there to prevent conflict and division but he was murdered for his efforts. Walls, borders, militarism – they all have their consequences.

Angela Merkel would know this. On her Dublin visit, the German Chancellor spoke about how she grew up in an East Germany cut off by the hard border of the Berlin Wall and she remembered what it was like. It was an extraordinary statement.

And great credit goes to the Irish Government for hosting this event and for having the German premier sit for an informal round table discussion with ordinary people from the Irish border area. They told her what it was like to live with these barriers and disruption. The imagery was poignant and powerful.

Read more: To solve the Brexit crisis, time to put special status for Northern Ireland back on the table

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar. Image: Getty.

Once again, as with so much concerning the ongoing car crash that is Brexit, one has to ask: how did the British not see this coming? How did any of us not see this coming?

But maybe we should have. Germany has long been quietly very grateful for Irish support on German unity when others were initially against it.

Back in 1990, the then premiers of France and Britain, Francois Mitterand and Margaret Thatcher, cautioned against the too hasty reunification of Germany, under Helmut Kohl. But Ireland, mindful of its own hard border and divided territory, was very supportive.

In 1998, with the Good Friday Agreement, the vexatious border in Ireland, and the violence it had created, melted away. But now, with Brexit, new threats loom.

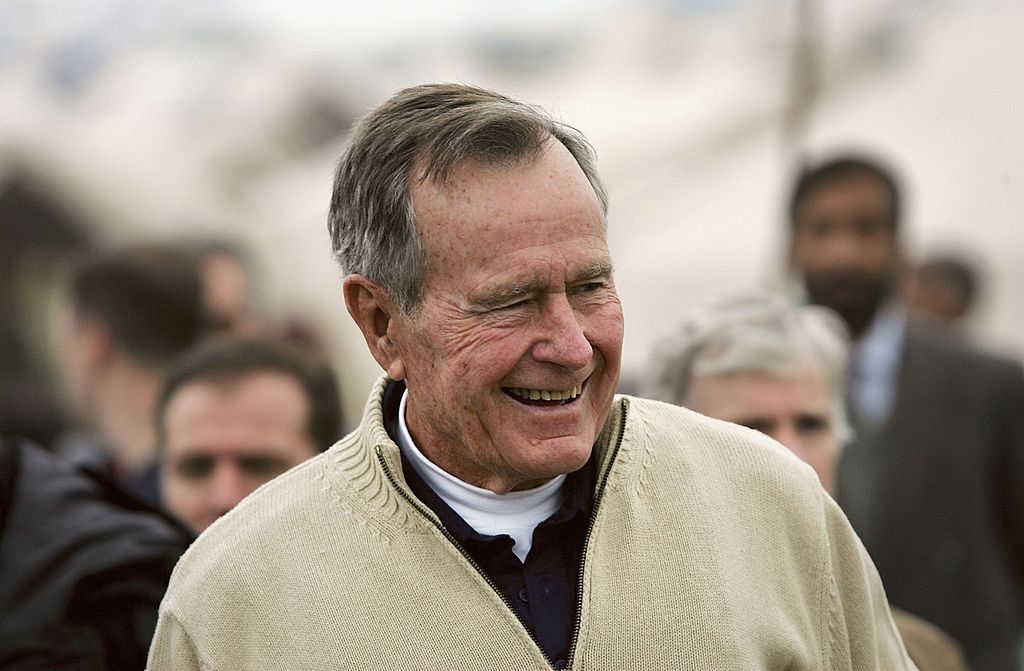

We often forget about this gesture in Ireland, but not in official circles in Germany. Interestingly, it is now suggested that another reason Ireland supported the Germans in 1990 was that the United States vigorously encouraged it to do so. Then US President George Bush Senior and his administration were strong supporters of Germany and of Helmut Kohl.

Read more: One third of British people believe Brexit makes a United Ireland likely

Former U.S. President George Bush visits a tent camp for earthquake survivors on the outskirts of Islamabad on January 17, 2006 in Pakistan. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Is it payback time now for Ireland? If so, it is very welcome. And it may also be payback time from the Germans, and from the EU generally, for Ireland for taking the hit on the bank bailout in 2008 and saving the European banking system.

This is something that is also not much remarked on, but it would be important background music. Especially with a belligerent and confused Britain trying to disrupt the party.

Either way, we are seeing a very welcome and impressive European unity as the chaos and confusion of hard Brexit looms.

It also further illustrates how Brexit has undone things and how the EU has questioned and challenged the notion of partition in Ireland in a fashion more effective than generations of Irish Republicans. Would that Eamon De Valera and Micheal Collins could live to see this moment!

Ireland's support for how Germany overcame its hard border has not been forgotten in Germany. In 2000, on the tenth anniversary of German reunification, the then German Foreign Minister thanked Ireland for its immediate support for the project and said that the Germans would ‘never forget it.’

So how did it happen?

Workers put up panorama pictures of German photographer Kai Wiedenhoefer that are part of his 'Wall on Wall' exhibition on a remaining section of the Berlin Wall in Berlin, Germany on July 9, 2013. Image: JOHANNES EISELE/AFP/Getty Images.

In the months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Ireland held the rotating Presidency of the EU (then the EC, or European Community), a much bigger deal then than it is now, in what was a less centralized EU, with only 12 members. So it was a major responsibility, and Ireland,a small country, was busily drafting the EU response.

Unusually, there were two separate EU summits in Dublin, with one dealing specifically with German unification. These were big events with big personalities involved – Margaret Thatcher, Francois Mitterand and Helmut Kohl. Ireland immediately supported German unification, which was in reality already underway, with Germans pouring across their country's former division. However, France and the UK, and other EU states wanted a major go-slow on such unity.

Having fought two world wars with Germany, British and French resistance was understandable. They were worried about German expansionism and Mitterand even quoted the old joke: “I like Germany so much I’d prefer to have two of them.” And even at the Dublin summit, Kohl didn’t ease these fears by likening the momentum for German unity to a “river that cannot be stopped.”

Other European states were worried that a reunited Germany, having got their way, might abandon the European project. But, in fact, the very opposite has happened, and now it is the UK that is abandoning Europe!

To his credit, then Taoiseach Charles Haughey provided crucial reassurance. He argued that securing German unity within the EU was the way around these fears and thus those Dublin summits cleared the way for the territory of then ex-Communist East Germany to join the European Community as part of a unified Germany later that year. And with no conditions or treaty changes.

Haughey saw that the heartfelt desire of Germans to come together was irresistible and peaceful. Communism had collapsed, there was a need for negotiations. Unlike the more wary Eurocrats, he was moved by the German story. “We have to stop the German bully,” Thatcher told him, but he ignored her.

Former Irish Taoiseach Charles Haughey. Image: WikiCommons.

Haughey was also a leader who, for all his faults, had real imagination and determination. He understood symbolism, and the sense of a moment, and the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the coming together of the German peoples was one of those historic moments.

The Germans were grateful for his full support and, at the second EU summit in Dublin Castle, I watched, as an eager young official, as the arriving and very happy Kohl almost bear-hugged the Taoiseach on Dublin Castle’s Battle Axe landing! Six years later, Kohl was back in Dublin, addressing the Dáil, and he was still thanking Haughey (and Ireland) for the strong support on German unity.

Though it was economically costly to West Germany, the reunification was completely peaceful, as was the transition from communism. But it might easily have been different. The East German Communist leader Erich Honecker was fully prepared to use military force to secure his communist regime until he was ejected by his own politburo.

On the tenth anniversary of the proposal to immediately admit the GDR directly into the EU, the German Foreign Minister, Guido Westerwelle described it as an “immensely important step, largely promoted by our Irish friends. It was a real milestone in the unification process.”

And then, switching to English, he added: “Thank you very much for what your country did for German unification. It was important in our history and we will never forget it.”

Read more: British MPs reject Brexit withdrawal deal for a third time

"We will do everything in order to prevent a no-deal #Brexit"

Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel says after talks with Irish PM Leo Varadkar in Dublinhttps://t.co/eFgVFtNYTS pic.twitter.com/18AveBzOPY

— BBC Politics (@BBCPolitics) April 4, 2019

I was back in Berlin recently and I walked along the old dividing line of this great city, once scarred by a high wall and armed sentries, all symbols of a long division. Nowadays, much of it is landscaped and there are poignant memorials and displays at places where people waved at each other across the frontier and were sometimes shot while trying to run across it.

It is such images that Angela Merkel will have been thinking of when she stood in Dublin and argued against the construction of a hard border across Ireland, an EU country. And, fittingly, she did so in the former stately home of a man who went to the Middle East to try to prevent conflict and division and who sacrificed his life in the process.

“For 34 years I lived behind the Iron Curtain,” Angela Merkel said clearly in Dublin “so I know only too well what it means once borders vanish, and once walls fall.”

But where's a will, there's a way, added the Chancellor hopefully, in terms of finding a solution.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments section, below.

Comments