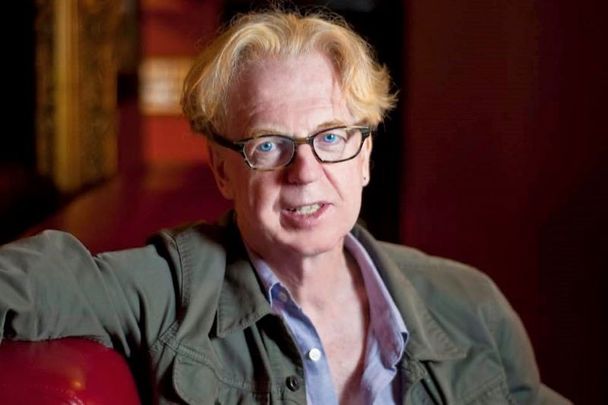

Editor's Note: Larry Kirwan, former frontman of Black 47, was recently nominated for a Tony Award for "Paradise Square." Here, we share an abridged version of his 2019 interview with author which was featured in McEvoy’s book, "Real Irish New York," published by Skyhorse.

By the time Larry Kirwan reached manhood, the stagnant Irish political life and the heavy influence of the Church led him out of Wexford and into Dublin—where he says he lived “a Gingerman existence”—then onto New York.

"So, Pierce Turner and I left Ireland, formed Turner and Kirwan of Wexford, and went to work at the Bells of Hell [in New York City]. ‘Land of de Valera’ was a parting shot. I resurrected the song in 1989 when Black 47 formed and it became a Reggae/Rap type anthem in those wild early years of the band.”

He says: “I didn’t find it hard to leave Ireland at all. I was always going and because my father was a deep-sea sailor, I was used to him going away for four or five months at a time.

Word soon spread throughout the East Village that Turner and Kirwan of Wexford were hot, which is surprising in that Kirwan never had a music lesson in his life.

“Just picked up the guitar,” he admitted, “a couple of people showed me where to put my fingers and I took it from there. I wish I had taken piano seriously. I figured out piano and guitar chords and learned how to place them, especially from writing songs—how to interject an obtuse chord that would necessitate a change in melody.

"I never took a lesson in playwriting either, learned everything the hard way, through listening to actors interpret your lines, and learning how to direct them.

"Same with novel writing, it’s often seemed to me like a process of learning how to eliminate mistakes, with the occasional ‘eureka’ moment. But with all three it’s a matter of telling a story. That’s a primal talent, and one that we Irish—like most dispossessed people—have a talent for.”

Larry Kirwan’s musical metamorphosis went in three phases. First, there was Turner and Kirwan of Wexford. “We had only one interest—music,” wrote Kirwan. “All else would provide for itself. We never gave a damn about tomorrow. That was a concept for the straight and the bored—two things we were most definitely not.

"On the plus side, we both could write, sing, play, arrange, produce, and go totally nuts on stage. I suppose we may have canceled each other out somewhat, but we were oblivious as to how the world perceived us. If there was magic in the moment, then the moment was what we were all about.”

Turner and Kirwan of Wexford eventually became Major Thinkers. They toured for years and their last performance was on St. Patrick’s Day, 1985—after the band was cropped by Epic Records.

“This new reality or malaise went way beyond money, however,” confessed Kirwan. “I had grown sick of the rock life and, not by coincidence, sick of myself, too. I had been on a nonstop roller-coaster ride for thirteen years and I couldn’t even recall the original reason for stepping aboard. I had come to America for what? Some vague notion of ‘making it?’ But making what? I wasn’t even sure what the concept meant anymore. I had no interest in a big house in Malibu. Nor was I desirous of owning fast cars or even faster women.

"But what the hell did I want? I had to confess that I didn’t have a bull’s notion. I did want to create. But what did that mean? Write songs? Form a band? None of it appealed to me anymore.”

This led Kirwan to a four-year musical hiatus when he worked at the writer’s craft, which he found challenging.

“In no time at all,” he wrote, “I realized why so many playwrights, and writers in general, become alcoholics. It’s a bitch of a game with long hours, much loneliness, and little, if any, financial reward, not to mention that the perfect play has never been written.

"Still, I had plenty of time on my hands and nothing else on my plate. In other words, playwriting is not for the faint of heart! It takes time and it changes you—not always for the better.”

Kirwan’s first writing project was a play about the Beatles called "Liverpool Fantasy." “I had been sketching out an idea for some time about what would have happened if the Beatles hadn’t made it,” he wrote. “I suppose I was still wrestling with the ‘making it’ syndrome.”

To put it mildly, it caused a stir. “Liverpool Fantasy,” Kirwan recalled, “almost shut down the house during the post-workshop discussion. What in the name of God was I thinking, and how dare I desecrate the memory of the warm and fuzzy Saint John? That seemed to be the majority opinion; while again, I had a sizeable body of supporters who thought I was only half-mad and deserved, at the bare minimum, the right of free speech.

"I decided that I’d put all my eggs in one basket and go for a production of 'Liverpool Fantasy.' To say that I couldn’t even get arrested with this play might be stretching a point, but it was certainly declined by the many theaters and producers to whom I submitted it.”

As he had with the music business, Kirwan was soon to learn that the theatre business was cutthroat in its own unique way.

“I received an amazing eye-opener into the convoluted theatrical world of New York City, its many delights and pitfalls. Coming from the cutthroat world of rock music with its much higher budgets and expectations, theater was at once archaic, far more principled, intellectual though often harebrained, and world away more bitchy.”

With the help of actress-turned-director Monica Gross, Kirwan rewrote the play and got it performed off-off-Broadway at a little theatre named El Bohio in Alphabet City. "Liverpool Fantasy" was also performed at the Dublin Theatre Festival in the Eblana Theatre in the basement of Busaras. It was now directed (in a way) by Kirwan himself, and had a chaotic, albeit successful run.

His next playwriting project was called "Mister Parnell," about the “Uncrowned King of Ireland” Charles Stewart Parnell and his fall from grace—helped tremendously along by the opposition of the Catholic Church—because of his affair with the married Catherine O’Shea.

“I only had to look inside my own heart and mind,” wrote Kirwan, “to witness firsthand the repression that dogmatic Catholicism fosters. As a boy, I had revolted against it because Catholicism failed to take account of our natural sexuality. I had also bucked against its Northern counterpart because it had allowed the good side of the message—the unhindered communion of the devotee with God—to become distorted into a discriminatory hatred of Catholics and Catholicism.”

"Mister Parnell" was finally performed in the early ’90s at Synchronicity Space in Soho.

“I was surprised,” said Kirwan, “that it never received another production as it’s a hell of a story. My grandfather’s family in Carlow had taken opposite sides in the split of 1891 over Parnell being named in the divorce of Catherine and William O’Shea. So, I had an inside look at the man through the eyes of my family. I might revisit it at some time but there’s a claustrophobic Victorian darkness that tends to overshadow the tragedy.”

Black 47 did their 25 years and disbanded in 2014. It was time for a new life for Kirwan. He has gone from doing 2,500 gigs with Black 47 to under 20 nowadays.

“Many of those,” he says, “are two particular one-man shows for colleges and performing arts centers—'A History of Ireland through Music,' and 'The Story of Stephen Foster.' Occasionally I get a longing to do some rowdy rock and roll gigs and take those. But mostly I’m writing these days.”

“I still do the big three—playwriting, novels, and songwriting,” says Kirwan. “I really like the challenge of writing book, music, and lyrics to musicals. It’s very difficult, but I find it fulfilling, although it does drive me crazy from time to time.

"I have two new musicals that take up a huge amount of time, 'IRAQ,' and 'The Catacombs' about the life and times of Brendan Behan. I usually choose subjects that challenge me to learn or confront some new skill. For IRAQ, I had to come to terms with quarter-tone Arabic music and fuse it with the punk, hard rock and hip-hop sounds that the troops were experiencing during the early years of the war. And with the Behan piece, I’ve fused Sean Nós with a Broadway sensibility.

"I also have a new novel, 'Rockaway Blue,' that will be published by Cornell University Press. It’s a post-9/11 novel and something that I’ve been working on for some time. For me, New York is either pre-9/11 or post-9/11 and I wanted to show that through the eyes of a family who had to deal with great loss and make sense of it—if such a thing is possible.”

In 2017, his play "Rebel in the Soul" was produced at the Irish Repertory Theatre in New York. It is the story of the Mother-and-Child Scheme that rocked Ireland in the early 1950s. Mother-and-Child was proposed by Dr. Noel Browne, the Minister for Health in the John A. Costello’s coalition government, and was supported by Seán MacBride, the Minister for External Affairs. It was a health and insurance plan that sought to fight the high rate of child mortality in Ireland, much of it caused by the high incidence of tuberculosis. This seemingly good plan was opposed by the Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, because it ran counter to “Catholic moral teaching.”

Like most authors, Kirwan has a great affection for the people he is writing about. “They are all gloriously flawed—despite being three of the great men of their times. Because of the structure of the play, we get a chance to observe them early on in private moments and can take their measure. They are soon caught up in a crisis, in many ways beyond their control, and we see them under pressure and often making wrong decisions.

"Rebel in the Soul" had been a work-in-progress for many years before it finally hit the stage.

“It’s not unusual for a play to take four or five years from conception to production,” Kirwan said. “There were some other factors in this case too. When we decided to disband Black 47, I went on the road for a long period and we made a final album, 'Last Call'. Then my musical 'Hard Times' became a success and is now being developed for a major production. These and other factors caused 'Rebel in the Soul' to be put on hold for several years. But Charlotte Moore had always been attracted to the play, the era, and the characters; and I guess the timing was right for her.

"As ever, it’s great to work at the Irish Rep—like coming home to family. It’s the perfect place to watch these fascinating Irish characters come to grips with an issue 67 years ago that’s roiling the U.S. right now—healthcare and insurance. To add fat to the fire, the decisions they made under pressure back in 1951 led to the shaping of Ireland as we know it today.”

Kirwan credits Charlotte Moore, the Artistic Director and Co-Founder of the Irish Rep, for helping him develop the play.

“The first drafts of the play had only two characters, Browne and McQuaid. After an early public reading at the Rep, Charlotte suggested that I expand the work and include MacBride, since he was often mentioned in the text. Browne, MacBride, and McQuaid are very dynamic characters who make mistakes under pressure—a good foundation for any play.”

Writing "Rebel in the Soul" while out on the road in the final years of Black 47 has had a therapeutic effect on Kirwan.

“Writing keeps me sane while on the road. There’s an intensity, and a focus on the ego when you’re touring and playing.

"But when I’m in a hotel room after the gig, and I begin to deal with three charismatic figures like Browne, MacBride, and McQuaid, I become a boy again back in Wexford, questioning my grandfather on politics and the times, and digesting his answers. The hours speed by as you turn historical figures into dramatic characters.

"Tighten the screws, heighten the pressure, deepen the intrigue, and you bring a special moment in time shimmering back to life. Before you know—it’s morning, you’re rip-roaring and ready to hit the road again.”

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of the recently published "Real Irish New York: A Rogue’s Gallery of Fenians, Tough Women, Holy Men, Blasphemers, Jesters, and a Gang of Other Colorful Characters." He is also the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising," and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," both now available in paperback, Kindle, and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website and Facebook page.

Comments