There may very well be no business like show business, but when it comes to mounting a show on Broadway it can be a very tough and demanding business.

Convincing financial backers while also polishing the gem of a concept into a stage play with the additional challenges of producing music and choreography for a musical is a mighty feat for those who relish the dream and have the commitment to see it through…or should be committed to an asylum.

The perils of production must all be navigated on the road to a Broadway stage, and seemingly the worse hazard you will face comes on opening night when the professional theater critics can undo all that you have achieved with the weight of their keyboard. It goes with the territory, but after seeing the new Broadway show Paradise Square inspired by a play called Hard Times a decade ago by musician and writer Larry Kirwan last Saturday afternoon, I wondered how it would fare. The rake of reviews that ensued offered some stern and dismissive critiques which require a strong conviction to weather storm clouds that could be gathering afterward.

Read more

Kirwan’s original play produced for performances at the Cell for the Irish Writers and Artists Group (which admittedly I did not see) focused on the checkered legacy of the American composer Stephen Foster back in the early part of the 19th century. Despite being one of the most successful songwriters in the era, he died penniless at the age of 36 in New York City. His involvement in minstrel shows in the volatile era before the Civil War is a gold mine for revisionist history, especially when you think of the evolution of show business and stage shows here.

Kirwan’s Hard Times definitely tapped into a vein worth exploring and developing, and so began a decade-long project that led to Paradise Square. Veteran Broadway producer Garth Drabinsky saw the potential in the dramatic story of life in the hardscrabble Five Points neighborhood of New York teeming with immigrants mixing with the black community living in New York with an interesting collaboration for some of the Irish and Afro-Americans playing out as well. Working with Kirwan and others, they workshopped it in Berkeley five years ago and then aimed for the Great White Way, with a full stage production in Chicago last year.

Along the way, more and more aspects worked their way into Paradise Square which was built around a previously unexplored dynamic revolving around closer relationships between the Irish and black population in the period leading up to the Civil War and during it.

Previously, history only shed light on the tensions exposed in Draft Riots of 1863 in New York City pitting the Irish against newly freed slaves by President Lincoln. A wider storyline depicting the affinity for two groups vying for the same low rung on the societal ladder in that impoverished setting brought in more creative people to accomplish that along with the need for many “co-producers” to raise the cash.

What finally arrived at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre at 243 West 47th Street is a hyperactive production for well-attended previews leading up to its opening on April 3. Kirwan’s original concept was further developed by Christina Anderson and Craig Lucas for the book, Nathan Tysen and Masi Asare for lyrics along with the musical director Jason Howland. It was a wise decision to reduce the music of Foster to a limited usage and rather inject a character who portrayed his flawed persona.

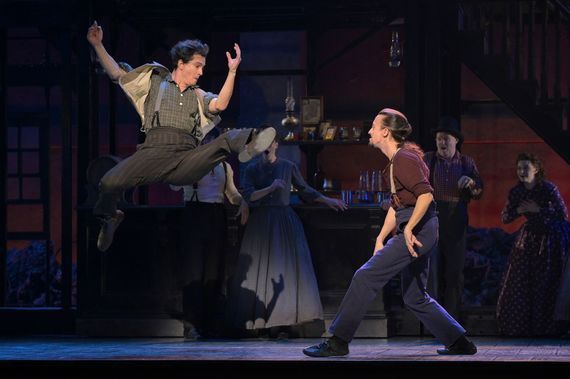

The superb choreography was led by Billy T. Jones, who leaned on Hammerstep founders Garrett Coleman and Jason Oremus to integrate their Irish stepdance with some urban hip-hop flavor that further blended with the African movements quite handily. This observer and a number of others whom I discussed the play with would agree with many of the critics that the dance routines helped carry the show throughout.

Standouts were the dancers like leads A. J. Shively as a newly arrived Irish immigrant Owen Duignan, and Sidney Dupont as a runaway slave, Washington Henry. The ensemble cast layered on top of this pair who later provided the big dramatic dance competition in the second act that led to other storylines was well chosen and reflective of the diverse communities they represented in the play.

The setup of creating a fictional Five Points saloon and brothel called Paradise Square where two interracial couples running it symbolized the “amalgamation” taking place in the era despite the historical tides against it in that era.

First and foremost was the owner Nelly Freemen O’Brien played by an extraordinary actress and singer, Joaquina Kalukango, married to a Union soldier and Irish immigrant sent off to fight for the Union (played by Matt Bogart). Her sister-in-law and bar manager Annie Lewis (played by Chilina Kennedy) was married to the Protestant Black Minister Samuel Jacob Lewis (played by Nathaniel Stampley).

Kalukango’s performance is key to this whole production, as the award-winning actress and singer never waivers in delivering the necessary spoken lines or lyrics that drive home much of what the play is about. In fact, her epic rendition of “Let it Burn” as the penultimate song in the show brings the audience to their feet before it even finishes and affirms the star’s importance in bringing the crowd along the multifaceted visit to a time and place of importance in our history.

Paradise Square is earnestly entertaining while driving home lessons that still need to be learned when it comes to dealing with immigration, integration, and racism in the U.S. It may have been a long road to bring the show to Broadway, but think about the tumult in the U.S. over the last five years revolving around issues of immigration and racial justice in that time frame. Those who do not learn the lessons of history are inclined to repeat it.

Run, don’t walk, to see Paradise Square, and read whatever critics' reviews you can find for further context on what you will experience and do your own research and soul-searching. Good theater inspires us to do so.

Comments