Antrim: The town of Bushmills is located between two of Northern Ireland’s most iconic tourist attractions.

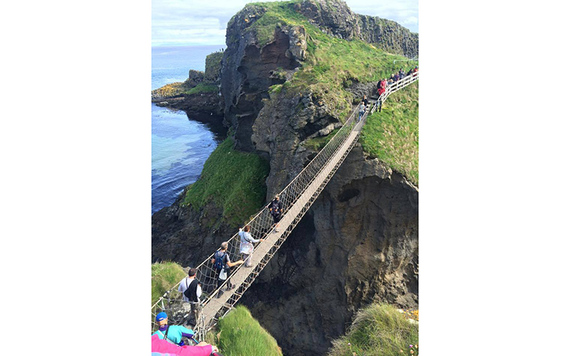

The Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge was built by salmon fisherman 350 years ago and links the tall cliffs of Antrim to a small island some 66 foot away.

Honestly I’d never heard of the place until a few months ago but was charmed upon arrival. The seawater that surrounds the island is the most astonishing turquoise color that I’ve never seen previously in Ireland and whilst the area is clearly popular with tourists, the sounds of so many languages were almost obscured by the cries of the hundreds of birds nesting on the island.

Fulmars and razorbills nest on the almost vertical cliffs and hunt for fish in flocks on the not too distant horizon.

Back on the road to Bushmill, it’s hard to ignore the political allegiances of local people in the Glens of Antrim as red, white and blue flags and bunting dominates villages.

Helpful explanation of how the Union Jack evolved.

Perhaps they’re only there because it’s a week before the Twelfth of July when loyal Protestants celebrate the defeat of the Catholic King James at the hands of the Protestant King William but, I suspect, most of the flags will still be flying in August. There’s a handy sign explaining the development of the Union Jack over the centuries suggesting a permanence about the exhibits.

Read more: Day 1 - Landing in beautiful Belfast on Norwegian Air’s inaugural flight

The Glorious Twelfth typically involves the burning of bonfires and in Bushmills town center a sign alerts drivers to a someone selling “Bonfire Wood Only”. Perhaps that’s why the local hotel uses turf for its fire?

More subtly, the local newsheet, the Bush Telegraph, hints at the town’s euroscepticism when it informs locals that that the brackets used to hold banners complied “even [with] EU regulations” - for which read burdensome red tape. Like most unionist areas of Northern Ireland the town gave the European project a red card (or should that be red hand?) in last year’s referendum and in North Antrim they did so by the largest margin in the province.

The town is also home to not one but two monuments to British forces. The first commemorates all those from the town who died in the two World Wars and a statue of a grimly determined Ulster soldier gazes down on all who pass.

War memorial.

The second is of Robert Quigg, a local boy who won the highest award in the British Army, the Victoria Cross, for “most conspicuous bravery” during the Battle of the Somme; seven times he entered No Man’s Land and each time he returned with a wounded comrade.

Robert Quigg, a local boy who won the highest award in the British Army.

What 1916 is to Irish republicans, the Somme is to Irish unionists; in Ulster folklore, it is regarded as something of a blood sacrifice when so many young lads died fighting for the King and Country that it became almost impossible for English politicians to betray their loyal families by handing them over to Dublin rule.

Unveiled last year by Queen Elizabeth II for the battle’s centenary - the monarch’s choice of a green outfit was described by one local as “apt” - the newly laid wreaths of poppies testify to the enduring scar of the Great War on small towns and villages the length and breadth of Europe.

But Antrim has not just been home to servants of the Crown but also of rebels against it too and it is among the Glens that the remains of relatives of Roger Casement lie buried.

Casement was once a British diplomat but retired to this heavily loyalist corner of Ireland only to become convinced of the cause of Irish freedom. When the First World War broke out this Knight of the Realm gave succor to Germans looking to invade Ireland - leading to his execution by the British.

Fifty years on the British Government released his body from a prison grave for reburial in Ireland but on the strict condition that it would not be interned in Northern Ireland - then in the grip of the Troubles.

The Irish Government gave him a state funeral but to this day his final wish to lie in the soil of his beloved Antrim remains unfulfilled.

On to the nearby Giant’s Causeway and I find suddenly we are surrounded by fellow sightseers once again. Carrick-a-Rede seemed busy until you happen upon the Causeway and you realize the rope bridge is almost deserted by comparison.

Each year the Causeway clocks a million visitors and is one of the eight Wonders of the World. There are buses to take you on the short journey from the visitor center to the causeway itself and an audiobook to elaborate how it was formed.

It was worth doing for sure, it is an icon of Ireland after all, but I preferred the quiet charm of Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge.

Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge.

Next up is Derry and although it’s only 40 miles away from the Causeway I can already sense a subtle cultural shift as we cross from the land that gave Ian Paisley a seat in Parliament to the city that raised Martin McGuinness.

For the first time I find evidence of an Irish identity: a store dubbed simply the “Irish Shop” displays a “Fáilte Isteach” (Welcome In) sign and a bilingual notice that smoking is not allowed.

Protestants have a long history of association with the Irish language, but sadly in Northern Ireland the language I love is highly politicized and remains very much a marker of nationalist identity.

Unlike in the Republic where public signage is bilingual, in the north it is strictly monolingual and I doubt I get a chance to use any Gaeilge until I head south on Saturday.

But tomorrow I’ll get to properly explore Derry, I suspect I’ll find even more differences as the day wears on.

Comments