On the night of June 20, 1631, the sleepy fishing village of Baltimore, County Cork, fell victim to one of the most devastating pirate attacks in Irish history. Over 100 men, women, and children were taken from their beds and forced into slavery by Barbary pirates—raiders from North Africa, led by a Dutch-born renegade known as Murat Reis the Younger.

But was this attack just an opportunistic plunder by pirates far from home? Or was there something darker behind the raid on Baltimore?

A town on borrowed time

For over four centuries, the lands around Baltimore were ruled by the powerful O’Driscoll clan. Led by Sir Fineen O'Driscoll, better known as Fineen of the Ships. The family enforced a toll known as “Black Rent” on any vessel passing through their coastal waters. Those who didn’t pay were quickly reminded of O’Driscoll’s authority by force.

In a strange foreboding of the fate that would later await Baltimore, Sir Fineen's eldest daughter, Máire, was captured by a pirate named Ali Krussa and sold into slavery in North Africa.

Whilst loyal to the Crown, Sir Fineen was reluctantly convinced by his sons to join the rebellion during the Nine Years' War, and his forces were present at the Battle of Kinsale.

To receive a pardon from Queen Elizabeth, he proposed allowing English settlers to settle on his land. Sir Thomas Crooke would lead these.

Crooke was an English-born lawyer and a staunch Calvinist who established an English colony in Baltimore.

The rise of English Baltimore

With the ascent of King James I, Crooke resolved to curry his favour and surrendered his extensive lands, granted to him by O’Driscoll. This was a clever ploy, as while King James was wary of Calvinists,m he was astute enough to realise the strategic importance of an English colony in rebellious west Cork. King James regranted the lands to Crooke, whose position was now greatly enhanced, and he resolved to grow the town of Baltimore with the aid of two hundred Calvinist settlers.

Baltimore was soon a prosperous town with numerous pilchard fisheries and a thriving wine trade.

In 1607, it became a market town, which entitled it to hold a weekly market and two annual fairs.

However, rumours persisted that Baltimore's success was not due to the hard work and endeavour of the English settlers but to piracy.

It was said that all the inhabitants, including Crooke himself, participated in piracy or aided pirates.

In 1608, Crooke was summoned to London by the Privy Council to answer to a charge of piracy.

One accusation was that the townspeople were slaughtering cattle to feed the pirate ships that anchored in the many hidden coves around Baltimore.

While the Privy Council was inclined to find him guilty, he was saved by an impassioned plea by William Lynn, the Bishop of Cork, who lavished praise on Crooke's achievements in creating a robust economy in Baltimore.

Acquitted of all charges, Crooke returned to Cork, but more trouble awaited him.

Enter Sir Walter Coppinger

From the foundation of his colony, Crooke and his fellow Calvinists faced opposition from Sir Walter Coppinger, a wealthy Roman Catholic lawyer who vehemently opposed English settlers in Cork.

Coppinger’s brother, Richard, was married to Eileen, the daughter of Sir Fineen O’Driscoll, and he believed that his family had far more right to Baltimore than the English colonists.

With a reputation for ruthlessness, Walter Coppinger filed numerous lawsuits against the settlers. Finally, in 1610, a settlement was reached when Crooke, Coppinger, and Sir Fineen O'Driscoll jointly granted a 21-year lease of Baltimore to the settlers.

By 1630, Crooke and O’Driscoll were dead, and Coppinger still harboured a desire to remove the English settlers and gain control of the land.

But a greater threat lay ahead of the citizens of Baltimore, that of the Barbary pirates.

The Corsairs come to Cork

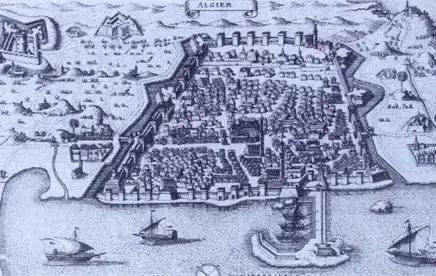

The Barbary pirates operated out of the Barbary Coast (modern-day Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya). They were known for raiding European coastal towns and capturing ships to take slaves and loot. They were supported by the Ottoman Empire and preyed upon Christian maritime and coastal communities.

By the early 17th century, their reach extended far into the Atlantic Ocean, with occasional raids on the British Isles, Iceland, and even Ireland. European powers, including England and Spain, often paid tribute to Barbary states to protect their ships, but coastal towns remained vulnerable.

One such pirate was Murat Reis the Younger. Previously a Dutch privateer, he hastily converted to Islam on capture.

Murat moved to the port of Salé in Morocco and began to raise his own crew, and forged a reputation as a skilful captain.

In 1627, Murat captured the island of Lundy off the Bristol coast, which was occupied by Barbary pirates for five years.

He set sail in 1631 and ventured one thousand miles, capturing two ships with little plunder.

Murat resolved to attack Kinsale, but one of his prisoners, Captain John Hackett from Dungarvan, informed him that it was too well protected, and his eye was then drawn to the prosperous town of Baltimore.

The night of fire and chains

Just after midnight on June 20 June 1631, Murat’s ship anchored off the coast, and more than two hundred pirates descended on the sleeping townsfolk.

The pirates came ashore under cover of darkness and quickly targeted the fishermen and their families, as well as anyone they could capture in the vicinity.

The pirates looted whatever valuables they could find, including household goods, fishing equipment, and any small treasures the people possessed.

Read more

The town was engulfed in flames as the pirates carried off 107 men, women, and children. They were taken to the pirate ships destined for North African slave markets.

More captives would have been taken, but the people of Baltimore rallied, and musket fire and the military beating of a drum persuaded the pirates they had enough plunder.

Captain John Hackett was captured by the survivors and arrested.

Captivity and aftermath

Those taken were sold into slavery across the Ottoman world. Men were forced into brutal labor aboard galleys. Women and children were sold as servants, concubines, or forcibly assimilated into Islamic households.

Only three women were ever ransomed and made it home. The rest vanished into history.

John Hackett, the man who guided the pirates, was captured, tried for treason, and hanged from a cliffside outside Baltimore.

The town, traumatized and vulnerable, was soon abandoned by its English settlers. Survivors fled inland to Skibbereen and other safer havens.

A town lost, a mystery remains

In the years that followed, Murat Reis rose through the ranks and became an admiral in the Ottoman navy, leaving piracy behind. The poet Thomas Davis would later immortalize the raid in verse, ensuring it would never be forgotten.

But the question still lingers: was the Sack of Baltimore just bad luck, or was it something more sinister?

Had John Hackett been acting alone? Or was someone else feeding information to Murat’s crew?

Sir Walter Coppinger, who had long sought to rid Baltimore of its English settlers, finally got his wish. Whether by fate or design, his enemies were gone.

History leaves no clear answers, but the silence that followed the flames of Baltimore still echoes along the Irish coast.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments