Joe McCann was already an IRA folk hero when he was gunned down by the British army in his native Belfast on 15 April, 1972. "On the run", the 24-year-old McCann was reputedly the most wanted man in Northern Ireland.

Stories circulated of ‘Big Joe’s’ exploits in the gun battles that followed the imposition of the Falls Road curfew in July 1970 and the introduction of internment without trial in August 1971.

Read more

Life magazine then published a photograph, taken on 9 August 1971, of him in silhouette, with an MI carbine resting on his knee and a barricade blazing in front of him, as he and five comrades pinned down a larger force of British soldiers in a seminal firefight.

OIRA man Joe McCann with MI rifle after firing on soldiers from behind blazing bread vans on Eliza street; 9 August 1971 pic.twitter.com/dXc3fRE9Y9

— ConflictNI (@ConflictNI) August 9, 2018

As Life put it: "Joe was a tall, thin man who moved only in leaps and crouches … He was an absolute hero to his men, mostly neighborhood irregulars, and as he directed them with grunts and waves of the American semi-automatic carbine he carried in one hand, he looked as though all Ireland were at stake on Eliza Street."

For twelve hours in this firefight, before being surrounded and broken up, Life reported, McCann had effective control of the Markets district in Belfast.

Before sectarian divisions between Catholics and Protestants overcame the civil rights movement in the North, he had been an active campaigner for better and fair public housing allocation. In October 1968, McCann was photographed in a march to Belfast’s City Hall carrying a placard demanding ‘Civil rights for EVERYONE’. He remained loyal to the Dublin-based leadership when the IRA split towards the end of 1969 into what became known as Officials and Provisionals.

On 15 April 1972, paratroopers shot McCann in controversial circumstances. Refusing to halt when challenged by a patrol in the Markets, he turned and ran. Eyewitnesses were adamant that ‘Big Joe’ had been shot once and wounded in the leg when he fell. But a soldier then fired at least ten rounds as he lay on the ground. Media coverage of his killing highlighted the army’s rules for the firing of weapons, and, specifically, whether it had a ‘shoot to kill’ policy.

His killing led to a weekend of rioting and attacks on army posts. The Official IRA killed two soldiers in Derry and an officer in Belfast. The next day, two civilians were killed by the army. Locals in the estate where McCann lived with his family said he had been ‘murdered’ by the army, and, with black flags ‘everywhere’ many wept as his coffin was carried to the church.

Led by a lone piper and his Irish wolfhound, McCann’s military-style funeral on 18 April 1972 was the biggest seen in Belfast up to that point. Around 100 women carrying wreaths followed the Tricolour-draped coffin, as did four MPs, including the internationally-known civil rights leader Bernadette Devlin. The funeral procession included an Official IRA contingent and Provisional IRA members, and thousands lined the route to the cemetery.

An extensive security operation with checkpoints was put in place across the city on the day of the funeral. At the graveside, Cathal Goulding, chief of staff of the Official IRA, made what the New York Times reported as "a dramatic and unexpected appearance after slipping into Belfast under the eyes of the soldiers". In his oration, Goulding said that McCann had been "murdered" by "the agents of imperialism and the Orange junta" in the North.

In his short but dramatic career, McCann impressed many, including some of his political adversaries. From prison, a leading loyalist paramilitary figure, Gusty Spence, wrote in a letter of condolence to McCann’s widow: "He was a soldier of the Republic and I a Volunteer of Ulster and we made no apology for what we are ... Joe once did a good turn indirectly and I never forgot him for his humanity."

McCann’s funeral made an impact beyond Belfast. The British Prime Minister Edward Heath demanded to know why no arrests had been made and questioned the army’s policy in relation to arresting IRA leaders who appeared on public occasions. In Washington, the State Department heard that the killing of McCann, and the issuing of the hotly-disputed Widgery report into the Bloody Sunday shootings in Derry, had boosted support for the IRA. In London, a senior member of the government admitted to the Irish ambassador that the British had made "a martyr" of McCann.

Described as a "Che Guevara" figure to the New York Times, it was fitting that Jim Fitzpatrick – the artist who created the Che poster – should do the same for 'Big Joe’.

Paratroopers gunned down Official IRA volunteer Joe McCann on 15 April 1972 in Belfast. British prime minister Edward Heath wanted to know why no arrests were made at the funeral – a showpiece for the Official republican movement. @An_Phoblacht #Troubles #IRA pic.twitter.com/M4KWcXDaSX

— John Mulqueen (@JohnMulqueen12) April 26, 2020

Another poster, ‘Soldier of the People’, became popular for a time. And ballads were written about McCann after his death, the best known recorded by Christy Moore. There is a commemorative plaque in the street where McCann fell.

However, the conflict in the North produced other ‘martyrs’ and they too have their tributes. What makes him stand out in Irish republican memory is the black and white photograph of him made famous by Life, one of the most iconic images of the Troubles.

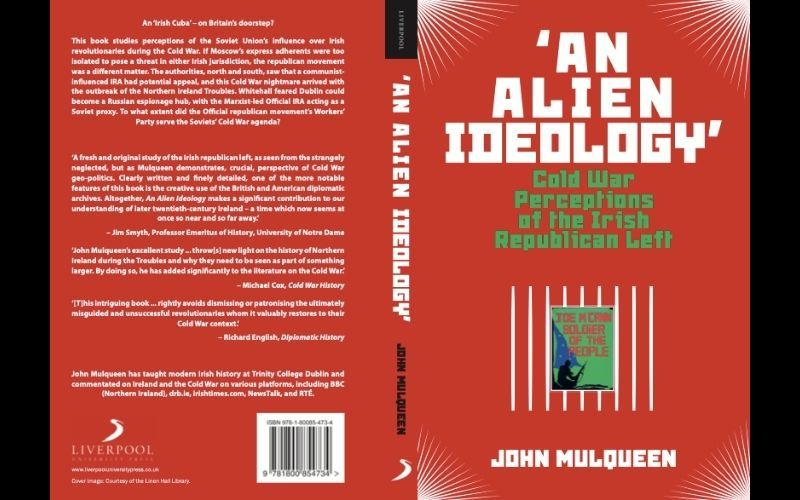

*This piece was submitted to IrishCentral by John Mulqueen, the author of "An Alien Ideology: Cold War Perceptions of the Irish Republican Left" (Liverpool University Press, paperback, 2022).

"An Alien Ideology: Cold War Perceptions of the Irish Republican Left"(Liverpool University Press)

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments