In a 2023 project conducted by Ancestor Network to research the completeness of early Civil birth Records, some clear examples were identified.

The Ancestor Network study extracted around 400 baptismal records from 36 random Catholic parishes in early 1864 and then established which of the births had been registered. The research uncovered many examples of spelling differences between the names recorded in the baptismal records and in the civil register.

These are interesting as they involve the same child, in the same region and within a short time period. Baptism of a Catholic child generally occurred within a few days of birth, while civil registration was required within three weeks of birth.

The parties to the above process are the person registering the name, the Catholic Priest, and the District Registrar. The latter were medical doctors, and almost all (700 of the 756 appointed in 1864) were also the Medical Officers in their Poor Law Union.

What are the possible reasons for the name variations?

Accent

One source of variation in some forms of record is the way in which names may be distorted by local accents. However, both priest and doctor were local residents whose ears would have been finely attuned to accents.

Literacy

If the family member registering the birth is literate, we would expect that they would provide their preferred spelling, although that is difficult to validate at this remove.

If the person was illiterate, they would be at the mercy of the priest and doctor as to how the name was spelled. The 1861 census shows that 42% of the population was illiterate. This ranged from 34% in Leinster Province (the East and SE counties) to 63% in Connaught (the mid-West counties).

Anecdotal evidence would suggest that District Registrars were high-status figures and few, even among the literate, would have questioned the way in which they spelled the names in the record.

Irish language

In 1861, 19% of the total population used Irish or Gaelic as their spoken language, and many of these would not have any English. The proportion varied significantly by region. Irish was spoken by around 40% of those in the Western counties of Connaught and Munster but by only 2% in the Eastern counties. Many of these would have recorded the birth using the Irish forms of their names, and the registrar or priest would have translated it into an English form.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

The degree of accuracy and sympathy with which was done would depend on the individual record-taker. Some registrars used similarly-sounding English names, while others attempted accurate synonyms of the Irish form. In regard to the ability of District Registrars to speak Irish, figures for 1864 are not available, but in 1901 less than 10% of medical doctors indicated an ability to speak the language.

In our research, we have also found instances where families used the ‘anglicized’ forms of their names for some purposes and the original Irish form in others.

Family custom

Robert Matheson published an exhaustive study on the variants that occurred in the early civil records of birth, death and marriage. In this, he notes that variation in the spelling of names sometimes occurred between branches, or individuals, within a family. However, we are here dealing with the parents of one child. It seems unlikely that the parents would willfully specify different name forms to the two record takers.

The logical conclusion is that the priest and the District Registrar were the ones who determined the spelling of the names in their respective record, particularly where the parents were illiterate.

We can logically suppose that each would draw on their respective local knowledge to determine the appropriate name form. Matheson notes that “Religious and social differences” cause variety in surnames.

Although it is a generalization, it may be presumed that priests in western counties' communities will speak Irish and have a greater cultural affinity with their parishioners. They would also have had a better understanding of local names forms than the doctor.

Doctors were almost all from a very different social class than their patients. In the 1861 census, 68% of medical doctors were from non-Catholic backgrounds while the population in most parts of the country was 80-90% Catholic.

In summary, each party would logically have rendered names into forms derived from their social experience, or phonetically if there is no obvious form. This is likely to be the major reason for the variations found.

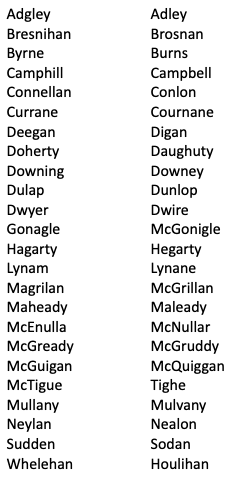

Below is a list of the more significant name variations found in our research. As might be expected, there were also many examples of minor spelling variations (Sheridan and Sherdon, McGee and Magee, Kilchrist and Gilchrist, etc.). However, there are also variations of a nature that might evade a researcher using logical variations in their searches. The most divergent was a child baptized as McVeigh (in Ballymacnab parish, Armagh) but registered as McCreagh.

Other name variations between birth and baptismal names include:

Variations between birth and baptismal Irish names.

These are offered as cautionary examples to those who are unable to find their ancestral names within the records. A broad interpretation of the possible spellings may be required to find the record you seek.

* For more information visit www.ancestor.ie.

** Originally published in 2023, updated in Oct 2024.

Comments