At the beginning of the 18th century, poverty in Ireland was widespread. The country's population had doubled in 50 years to 6.5 million and it was estimated that there were two million people living in destitute conditions and starvation.

The British Government introduced remedies including public works projects, emigration, and the introduction of the Poor Law. By 1838 the English Workhouse System for the poor was introduced to Ireland.

~~~~~

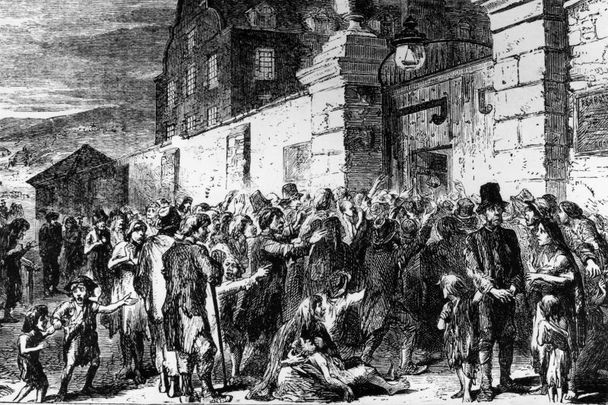

Below is historical evidence of the suffering that occurred in Country Clare under the Poor Law Workhouse rules.

The County Clare minute books are from two of Clare’s unions, Kilrush and Ennistymon. Both unions suffered greatly during the Famine, but it is said that few places endured as much misery as Kilrush.

In 1849, The Illustrated London News created a seven-part series on the new Poor Law in Ireland. Its series focused on the conditions of Kilrush and the large numbers of people who died, the thousands who were evicted, and many more who emigrated. Many of the illustrations created are iconic representations of the Famine in Ireland. One particular image is of Captain Kennedy’s daughter giving out food to the starving.

Captain (later Sir) Arthur Edward Kennedy took over the position of Poor Law Inspector in Kilrush in 1847 for three years. During his time he made powerful enemies, especially of the landowner and guardian, Crofton Moore Vandeleur. Vandeleur was known for his widespread evictions in the Kilrush Union.

The English workhouse system was introduced to Ireland in 1838 as part of the Irish Poor Law created, in theory, to help relieve the suffering of the poor.

However, this English system did not work as well in Ireland as it did in England. The Poor Law Commission divided the country into 130 poor law unions, which were eventually expanded to 163 unions. Each union was to have its own workhouse and a Board of Guardians.

The Board of Guardians was charged with the task of distributing relief to the completely destitute. They operated workhouses that were built to hold 600 to 800 inmates but were overwhelmed with thousands coming to their doors seeking salvation from disease and starvation.

Elections of the guardians took place every March 25. Only ratepayers were eligible to vote, which meant the landless Irish could not participate. Two-thirds of the guardians were elected and one-third were ex-officio guardians. Usually, the local Justices of the Peace or local magistrates were given the ex-officio positions. Religious leaders or ministers were not eligible to become guardians. This meant that the landed classes were disproportionately represented on the Board of Guardians.

The Clare Poor Law Unions Board of Guardians Minute Books documented weekly reports of how many men and women were housed; the amount of ‘lunatics’ or ‘idiots;’ how many were discharged or died and the number of births. They also recorded the workhouse expenditures like food supplies or salaries and the number of inmates receiving medical treatments.

In the books, we can get a glimpse of daily life in the workhouse and discover events or incidents that occurred in any week. For example, in July 1855, the workhouse schoolmaster wrote to the board of guardians complaining about the behavior of the pauper boys, who were acting like yahoos.

‘I beg to bring under your notice, the outrageous conduct of some of the working class of pauper boys in whistling and shouting like yahoos after people as they pass, and to suggest the necessity of using some effective means of making them less like savages and more like civilized beings than many of them are at present – their cursing, swearing and obscene language, their rudeness and brutality are often shocking and disgusting to the last degree. The present complaint is of the farm boy John…who (having previously caused much annoyance by his misconduct in the schoolroom) yesterday evening…set up whistling and shouting after me as I was going away after locking the schoolyard door.’

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

In other examples, we can discover more about the lives of those housed in the workhouse. In June 1855, the guardians recorded the names of some of the orphaned or deserted children. 2 week old Mary, an illegitimate child born in the workhouse, was deserted by her mother at the outer gate. The mother of Mary and John, ages 9 and 6, had died and their father ‘has for years left this part of the country’. 5-year-old Patrick’s mother left the workhouse hurriedly and his father was dead. The guardians also recorded any marriages that were to take place between any of the paupers. In May 1848, the minute book of Kilrush states: ‘Marriage is intended to be solemnized in the parish church of Kilrush between Michael Houlihan of the Glen, widower, and Anne Doyle of the same place, widow.’

By looking at the minutes from one full meeting you can get a snapshot of that week in the workhouse. This is excellent if you discover your ancestor was housed in the workhouse, then you can further piece together what their life was like. In Kilrush Union workhouse, on Saturday 16 January 1868, there were 346 people in the workhouse (far less than the overcrowded numbers of the Famine years). During the last week, 13 people were discharged or died. 193 were being treated in the hospital. An order was placed for: 1760 lbs of white bread, 480 lbs of brown bread, 45 lbs of officer’s meat, 121 lbs of pauper’s meat, 2,011 quarts of milk, 735 eggs, 14 lbs of pepper, ½ gallon of whiskey, 15 lbs of candles and 112 lbs of soap. The weekly order could vary - the following week’s order did not include soap, pepper or whiskey, but did include 19 bottles of wine. The Matron’s report tells us that the women repaired 13 sheets, 24 women’s shirts, 19 men’s shirts, 37 girl’s shirts, 23 girl’s bibs, 9 women’s petticoats, and 8 boy’s overalls. One of the younger male inmates, John Cunningham, was taken for an apprenticeship with John Culligan, a tailor. During the week, ‘one of the women in bringing the milk to the infirmary yesterday fell and spilled 13 quarts of milk for which master had to substitute tea.’

The guardians would also record any notifications of evictions. During the Famine, thousands were being evicted. They were left deprived and sought temporary shelter in bogs and ditches. Eventually, many made their way to the overcrowded workhouse, but hundreds died before they could reach it. Prior to eviction, landlords would notify the local board of guardians. In June 1849, the Dublin Evening Post reported that a letter from Captain Kennedy, Poor Law Inspector for Kilrush, was read to the House of Commons regarding the evictions. He wrote that there have been 15,000 evictions in the last year and the homes of 20,000 were to be destroyed. The House of Commons debated whether to interfere with the evictions, but no changes to the law were made and the evictions continued.

The minute books are immensely important if your ancestor was in the Clare workhouse or even if you want to further understand workhouse life. The records are available on Findmypast in two formats. In the first format, you can search them by Name, Year and Union. The second format is a Browse feature, where you can pick a Union or minute book and read through it from beginning to end.

* Originally published in 2015, in association with FindMyPast, updated in July 2024.

Comments