“Everyone clings to their history with a vengeance, because it anchors their identity.” - Marshall B. Rosenberg

“Where’s is the accent from?” That’s been the single most confusing question of my entire life. I know the moment it is asked the answer will be judged, calculated and assessed.

I’ve learned to answer the question in one sentence: "I was born in Ireland, raised in Australia, but now I live in New York City." I figure I can be all of those things at once, but most folks would like you to accommodate them by being one.

My experience is not unlike a lot of immigrants who have left behind family, friends, country, and the monuments of their culture. This would be one way to consider the collection of songs I wrote and adapted about my forgotten ancestor 19th-century gang leader and colony chief James “The Rooster” Corcoran (aka Paddy Corcoran).

Writing songs requires a form of precognitive, somatic inquiry. A trance almost takes place when a song is born. It’s mysterious and ephemeral and yet it has some fundamentals that you’ve aligned: chords, keys, themes, and whatever research notes you’ve accumulated, but you only have your “epiphany” if that somatic state is entered.

Corcoran’s life similarly symbolized this disregard for rules. He was “outside” of society and his liminal location “Corcoran’s Roost” was a ghostly manifestation of an alternative existence, and thus as a subject and state of being a body of songs could be cleaned.

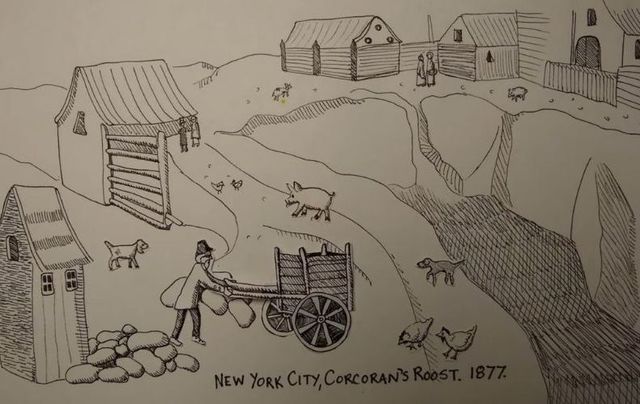

In 1844, James “The Rooster” Corcoran landed in New York City at the age of 25. He formed the Rag Gang down in the Five Points, and then moved uptown to be the tacit leader of a colony in the heart of Midtown Manhattan. “Corcoran’s Roost” was a shantytown that offered a safe haven for 90 families who were a part of a huge wave of Irish immigrants who flooded into America during the 1800s. Eventually, they’d represent nearly a quarter of the New York population, and they were “ill-viewed” by nativists.

I was chasing ghosts and I immersed myself in the tabloids of the 1800s that mentioned “Corcoran’s Roost.” I noticed that Corcoran’s rise to respectability obfuscated his connections with the gangs and his role in providing refuge to any man hunted by the police. In fact, it often seemed that the poor only ever end up being documented if they commit a crime.

I’m not a historian but a songwriter. Imagine, I thought, if I were a ballad singer from the 1800s who spread the local history, murders, deaths of the famous people in song what would I say about this guy?

I began immersing myself in more tabloids that presented Corcoran’s conflicts, as often the poor only ever end up being documented if they commit a crime. Each article brought me closer to a lost chain that linked me to a place in history and the present: It sort of dangled there for me to grab, and I felt I didn’t need anyone’s permission to reach up and grab it. I soon felt “emotions” unconsciously working beneath the surface connecting me with my Irish American phantom and my own identity.

The minimalist recording of "King Corcoran" begins with just two quick heartbeats of the ancient Irish hand drum or Bodhrán, and the vocals enter flat and unemotive for the exposition, as I introduce the idea of identity in the form of respectability outright, "King Corcoran was a gentleman/He came from decent folk.” These opening lines were not contained within any of the tabloid newspapers, but instead, I took them from ‘St. Patrick was a Gentleman’[2] The idea that Corcoran was by all accounts respected appears true on some levels, but also there are accounts of him also being feared.

The song continues his tale against adversity in America, and the finer details mention his shantytown, his wife’s legendary abilities as she strips the buttons from a policeman’s suit as charms for their shanty wall.

This “uncrowned King" of the “shanty people” still calls me, and songs still arrive seeking connection, and I still sense him around me as I write songs and I imagine him peering from the rocky eminence of the “Roost” and casting disdainful glances at progress passing in the street. I’m sure I’ll resurrect him again for a tour when the COVID-19 pandemic has less of a hold on the world.

[2] There are many versions sung of this song listed in Roud, 13337. The Bodleian has six broadsheet printings between by 1866.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments