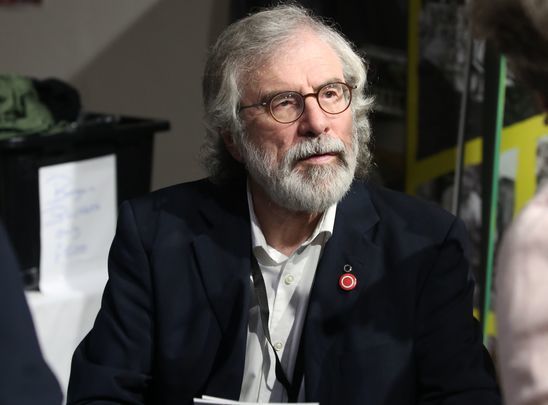

Everyone has their own idea of who Gerry Adams is but in his latest collection of short stories titled Black Mountain and Other Stories he shows us who the men and women of his home city are. It's a wide-ranging, authentic portrait of a spirited people by a writer who clearly loves them. Cahir O'Doherty talks to Adams about the book.

If you remember The Troubles then you already know the face of Gerry Adams. The president of Sinn Fein between 1983 and 2018, he also served as a TD for Louth from 2011 to 2020.

But a new post-Troubles generation was introduced to him via his wildly quotable Twitter account, which eventually resulted in his entertaining “little book of tweets” that The New Yorker archly described as a “mephitic haze.”

Critics like to claim the humor and whimsy of those tweets are a studied and deliberate front, a calculated ruse to make one of the most polarizing figures in Ireland seem like a bookish and slightly eccentric northern Grandad, but those who know him better say that's exactly who he is.

On the day I interview Adams, by Zoom, about his new collection of short stories titled "Black Mountain and Other Stories", one or two of his grandkids are just off-camera and they get a bit boisterous at times, leaving him to gently call for a little order in the Irish language, looking every inch the indulgent Granddad that his tweets suggest he is. But he is also, his latest collection reminds us, a longtime writer and political activist.

If Adams had written this collection under a pseudonym it would be clear in the first story that the writer had lived through the darkest years of The Troubles. The shorthand way he references the Belfast pogroms at the start of the conflict, pogroms that resulted in the largest forcible displacement of civilians since 1945, makes it clear that Adams has found himself in the heart of the crisis and he has seen it from multiple sides.

What you might not expect is that many of the protagonists in this collection are women who live and speak with a particular strength, humor, and outlook that rings true on every page. These aren't the sainted pieces of mythic Irish virtue of Yeats; they're much closer to the raucous working-class women of O'Casey, and Adams's stories are all the better for it.

The Black Mountain of the title is the mountain called Sliabh Dubh in Irish, the one overlooking Belfast but West Belfast in particular, an enduring image of permanence in a world of change that speaks to Adams and to his view that a campaign is not a place you arrive at but a journey that is long and ongoing.

The first thing Adams does in conversation is the Irish thing -- he asks me where I'm from. When I tell him Donegal he mentions that he lived outside my town for a month in 1984 after he was shot by a UDA gunman. He recuperated there with his wife.

And just like the stories in his new collection, he remembers the walks and the hills up there. The hills of that peninsula are ancient and enduring, I tell him. They are rooted to the place and the people.

Is that what the Black Mountain means in his own collection, I ask him? Because it survives everything, it remains unchanged through it all?

“We were up there in Donegal for a long time,” Adams tells the Irish Voice, “so you get to go to places and do the walks, and I have some very special memories of the place. And as for the Black Mountain as you very eloquently described, it's a touchstone. It's always going to be there. It's just a constant.

“If I go to the front door here the Black Mountains are above me. I hear from a good few Belfast people that if they're spending time up in Dublin and they're coming home, the moment the Black Mountain comes up, once it's on the horizon, they have a sense of coming home.”

He remembers a time before The Troubles of long summers spent up on that hill with gangs of other “abandoned mid-teens” scavenging for wild strawberries. From far up above the city they would all try to spot their houses.

“And it's become a generational thing almost, you bring your grandchildren up there now and almost immediately they start looking for their own homes. So it's a constant, that sort of long embrace of the hills that are wrapped around the lough.”

The title story is the tale of a long friendship between two men that begins in childhood and endures into their late sixties. They still love to take a gentle dander up to the hill – no longer a brisk walk, but the hills have been made more accessible – all the while bickering like two old friends over who had the harder time growing up and quietly getting the better of each other, or so they think.

Adams’ ear for the ways in northern men jokingly needle and provoke each other is flawless, and this story is so vivid that it seems to come directly from his lived experience, although he insists it’s all fiction.

“Well recently when I'd be going up through West Belfast or anywhere for that matter, you'd see schoolboys walking home from school. And they'd be engrossed in conversation, whatever they're talking about. And somehow you can see them at 60 years or 70 years or older because they have all the characteristics and the arm gestures.”

There's more to it though, he adds.

“I happen to think that friendship is one of the most important things in life. And I think that friendships should rise above everything, above politics even,” he says.

“You know I'm a political creature who practices politics every week, but I don't think it's important enough for me to fall out with a friend over. We should be able to have our political differences and then continue with our friendships.”

The 11 stories in Black Mountain and Other Stories are not all banter and good fellowship, though. They deal with bullying, betrayal, suicide and sexual abuse, and one follows an IRA sniper as he trains his gun on a British Army foot patrol.

Another puts a fake death note in the local paper to gin up enough sympathetic contributions to buy two tickets to the All-Ireland match. Wide-ranging doesn't cover it.

Adams also writes about how an angry mother deals with a schoolteacher who is publicly humiliating her son, a story inspired by his own real life experience of it. Another deals with a life-changing interracial relationship and how stringent Irish immigration laws make it impossible for that relationship to thrive. Unsurprisingly, grasping with the morality or lack thereof of the armed struggle is a recurring theme.

In another story, Adams addresses the way in which the Catholic Church frequently condemned republicans during The Troubles. We watch as an elderly woman upbraids a new priest who has just given a knee-jerk, condemnatory sermon about the men of violence in her church. She takes a different view.

“I know them that lick the altar rails and, God forgive me, they wouldn't give you a drink of water if you were dying of thirst,” she tells him, hoping to help him see sense.

The directness and humor of this language is very northern, as is the sense of outrage at the double standards often employed by clerics to remind people of their place. But you don't tell a Belfast woman of a certain age if she doesn't like the church's rules she can take herself elsewhere. That is to misunderstand the city, its struggles, and the natural deference – not to say admiration – for hard-working elders that usually prevails there. It's clear from the outset who will prevail.

Having him on the line, and conscious of his wider life's work, I also have to ask Adams if he sees a new urgency in the Irish unity debate?

“I've come to learn that struggle is a continuum. I very much see myself and those like me who are activists as part of that continuum,” he says.

“I think with the strength of Sinn Fein across the island, the issue of Brexit, the demographic changes in the North and so on we are in a new era of struggle. The most significant thing for me anyway, in terms of Republican struggle, was that we developed and negotiated the Good Friday Agreement, a peaceful and democratic way to end the union with Britain and that that's what people want.”

The movement of 1916 didn't have that, nor did the United Irish Society or Bobby Sands, Adams says.

“Now we have it. And Irish America still has a big part to play. You look at the interventions from Congressman Richie Neal to Nancy Pelosi to President Biden. I think we're in a very, very promising period.

“It comes down to people like the characters in my stories to get to know each other. There are persuadables in every society. And Irish America has kept the faith.”

(Black Mountain and Other Stories by Gerry Adams is published by Brandon Press, and is available on Amazon)

Comments