An extract from" Enjoying Claret in Georgian Ireland: A history of amiable excess" by Patricia McCarthy on the believed healing properties and subsequent health issues caused by the popular Bordeaux red wine.

From ancient times and throughout the eighteenth century, wine played a major part in medicine and in religious practices. The Greek Hippocrates (c. 450 BC) was the first recognized practitioner who, having experimented with different wines for various ailments, recommended wine as a disinfectant, a medicine and part of a healthy diet. The Good Samaritan, after all, poured wine (and oil) into the wounds of the traveler that he encountered. The Roman physician Galen (second-century ad) found through his experience of treating wounded gladiators that wine was the most effective disinfectant for wounds; the Talmud states that ‘wine is the foremost of all medicines: wherever wine is lacking, medicines become necessary’; and wine was a feature in the worship of Bacchus, the god of wine.

In the 13th century, Roger Bacon, the philosopher and writer on alchemy and medicine, suggests that wine could "preserve the Stomach, strengthen the Natural Heat, help Digestion, defend the Body from Corruption, carry the Food to all the Parts, and concoct the Food till it be turned into very Blood: It also cheers the Heart, tinges the Countenance with Red, makes the Tongue voluble, begets Assurance, and promises much Good and Profit."

"But", he warns, "if it be over-much guzzled, it will on the contrary do a great deal of Harm: For it will darken the Understanding, ill-affect the Brain … beget shaking of the Limbs and Bleareyedness."

John Dymmok, an Englishman who came to Ireland possibly in the service of Lord Essex, in his "Treatise of Ireland" (1600), tended to blame the climate in Ireland for the amounts of wine and other liquors that were drunk:

"The cuntry lyeth very low, and therefore watrish and full of marishes, boggs and standing pooles, even in the highest mountaynes, which causeth the inhabitants, but especially the sojourners there, to be very subject to rheumes, catarrs, and flixes [sic] for remedy whereof they drinke great quantity of hott wynes, especially sackes and a kind of aqua vitae, more dryinge and less inflamynge, than that which is made in England."

In the 18th and 19th centuries, people were not shy about discussing their health with each other, probably doing so in the hope that a cure or panacea would be recommended. From correspondence it can be seen that they kept themselves informed regularly regarding complaints, sometimes checking up to see how an illness might be progressing or otherwise, constantly giving advice and sending recipes (or ‘receipts’) of ‘cures’ that they had experienced or of which they had been informed.

In fact, it was expected that everyone had their store of medical ‘cures’, especially women, and those who did not were frowned upon, seen as being similar to a woman who was unable to bake, sew or manage the servants.

A collection of recipes and cures written into or collected in a notebook was an important item in every household. Until the late 18th century, most doctors in Ireland were quacks with some exceptions, one being Lord Trimleston from Co. Meath.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

Enjoying claret in Georgian Ireland distinguished botanist who had studied medicine in Paris. Surgery was extremely dangerous and often did not work, so bloodletting and blistering were frequently the treatments that were applied.

As one doctor put it in a letter to a colleague in 1818, "The superiority of bloodletting over wine, wine over bloodletting, will be successfully established two or three times in the course of every century."

Daniel O’Connell remarked that "almost all the diseases of persons in the upper classes do at middle life arise from repletion or over-much food in the stomach," which was probably true.

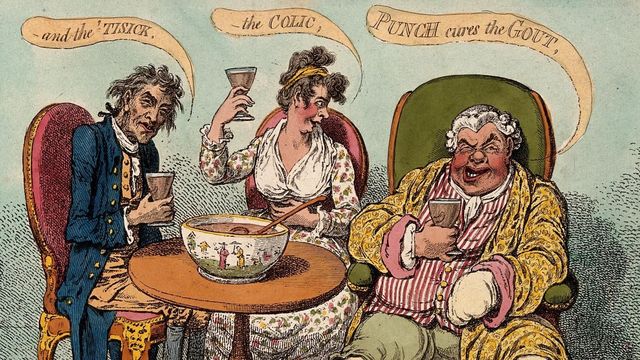

Among the upper classes, however, gout was the major health problem, particularly for men.

"Irish hospitality" had another meaning for Lord Orrery, who commented in a letter to a friend: "Lord Thomond is laid up with the Gout: the Irish Hospitality has broke out in his Feet, and pins him down to a great Chair and a slender Meal."

Orrery would have agreed with William Buchan who was of the opinion in "Domestic Medicine" (1784) that excessive alcohol and idleness can be the causes of gout.

In his book, "A Treatise on the Gout" (1760), Charles Louis Liger wrote that "in Great Britain there are perhaps as many if not more victims to this excruciating distemper than in any other part of the world."

It would seem fairly obvious that, given the amounts of wine consumed in Ireland during the 18th and 19th centuries, there would be numerous health problems, among them gout, about which the barrister Jonah Barrington had this to say:

"I have heard it often said that, at the time I speak of, every estated gentleman in the Queen’s County [Laois] was honoured by the gout … its extraordinary prevalence was not difficult to be accounted for, by the disproportionate quantity of acid contained in their seductive beverage, called rum-shrub, which was then universally drunk in quantities nearly incredible, generally from supper-time till morning, by all country gentlemen, as they said, to keep down their claret."

In her "Cooking Recipes and Medical Cures", Mary Ponsonby has a couple of remedies for gout: one was for "three grains of musk in a glass of Madeira or Tent sweetening it with sugar", while the recipe for the other sounds quite dramatic and required some muscle to prepare:

"Take one pound of stone Brimstone pound in fine and pour one Gallon of Boiling water upon it in a stone jar, shake it several times a day for 2 or 3 days then draw it off for use, take half a pint every morning an hour before breakfast. The jar to be kept close stop’d."

While the drinking of "the sober gallon of claret" consumed by many was considered to be utterly excessive, doctors too believed in the positive health aspects of wine.

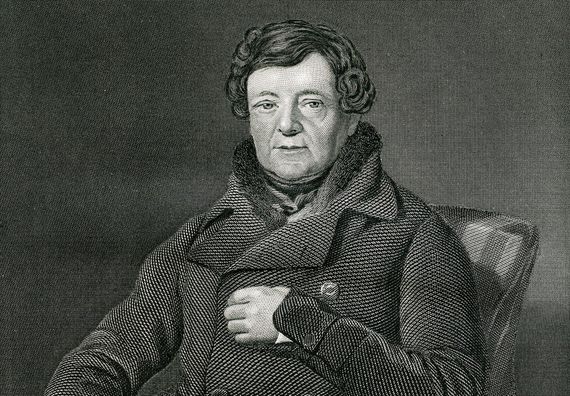

Daniel O’Connell, suffering from "a slow nervous fever", was advised by his doctor in 1794 to drink a bottle of port per day to cure it.

Daniel O’Connell.

Thomas Jefferson said, "I have lived temperately … I double the doctor’s recommendation of a glass and half of wine each day and even treble it with a friend".

For his daughter in her final illness in 1804, he recommended sherry: writing to his son-in-law who was with his wife at Monticello, "The sherry at Monticello is old and genuine, and the Pedro Ximenes much older still and stomachic. Her palate and stomach will be the best arbiters between them."

In France, a major commercial spat occurred between the French regions when Louis XIV’s physician recommended that the king should drink burgundy rather than champagne for his health.

Lord Byron recommended hock and soda water as a hangover remedy, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, regarding claret, insists in School for Scandal that "women give headaches, this don’t".

The earl of Chesterfield’s treatment, recommended by his doctor for an unspecified illness, involved "the consumption of substantial amounts of mercury and burgundy’ which he called ‘my two most constant friends".

Richard Lovell Edgeworth had his head shaved by his local barber in Edgeworthstown so that his wig would fit snugly, and whether it was the result of this, or perhaps to cure a condition like ringworm, he had his head treated with brandy. Even though drinkers and medical practitioners in the 18th century were fully aware that gout was a direct result of too much wine, it seemed to make little or no difference to their habit nor to the frequency with which they imbibed.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

A book such as "The Juice of the Grape, or, Wine Preferable to Water" (1724) did not help. The author points out that, taken in moderate quantities, wine had the answer to every complaint: it has "the power to sudden Refreshment, to warm the Stomach, gently stimulate its Fibres, promote Digestion, raise the Pulse, rarify the Blood, add to its Velocity, open Obstructions, forward Excretions, greatly promote insensible Perspiration, increase the natural Strength, and enlarge the Faculties both of Body and Mind".

Further, he believes that men "of a good Constitution, whose Parts are sound and Vitals untainted", suffer no ill-effects from "a continual debauch or excess in this exhilarating fluid, for a long series of Years; but always appear florid and gay, vigorous and lusty".

Well-run households had a book of recipes and remedies (sometimes referred to as "receipts"), used by the family and very often handed down from one generation to the next. A number of these can be found in family archives in the National Library of Ireland, and other places, and they make for interesting reading. From these, it is obvious that women exchanged recipes with friends whose names were noted in the recipe titles, or they would have read about recipes and/or cures and copied them into their books.

Included in these were remedies for a multitude of illnesses, such as for ‘the Plague’, ‘Hystericks’ or ‘To relieve the common Irish complaint of a pain about ye Heart’ – for the latter ‘strong tea made of peppermint or penny royal, add to this a little wine of any sort with some sugar, and take 3 spoonfuls a dose’. For a sore throat – gargle with ‘3 table spoonfuls of Claret, one of Vinegar, half a spoonful of Honey, a teaspoon of salt, a pinch of Alum, boil and scum it’; for a stomach pain – ‘Half an ounce of rhubarb, a quarter of a nutmeg grated in a quart of Madeira – take a small wine glass going to bed’.

It should be noted that there was no threshold age for children to be introduced to taking alcohol, as it was routinely used in both cooking and medicine.

To twenty-first-century eyes some of these remedies are quite bizarre, but perhaps anything was worth trying and, at the time, they were possible lifelines. Women took pride in their collections of remedies, frequently to be found written in notebooks together with their recipes.

Food, its quantity and its effect on a person’s health, did not seem to be of any real importance compared with the drinking of wine, which could and did cause ill-health but, according to the medical profession at the time, was also the remedy.

* An extract from "Enjoying Claret in Georgian Ireland: A History of Amiable Excess" by Patricia McCarthy (to be published by Four Courts Press in March 2022. Large Format. Full Colour Ills. €40.00).

Comments