The New York City subway system is one of the foremost metropolitan transit systems in the world today, but it can trace its origin to humble beginnings in County Cork.

The vast network of sprawling train lines in America's biggest city owes a debt of gratitude to John McDonald, an Irish famine emigrant from the Rebel County.

McDonald was responsible for the construction of New York's first subway line (between City Hall in Downtown Manhattan and 145th Street in Harlem) in the early 1900s.

He had a gargantuan task on his hands; to quickly build a train line underneath a rapidly expanding city, but he proved adept

McDonald began working on the subway tunnel in 1900, but his story starts long before that.

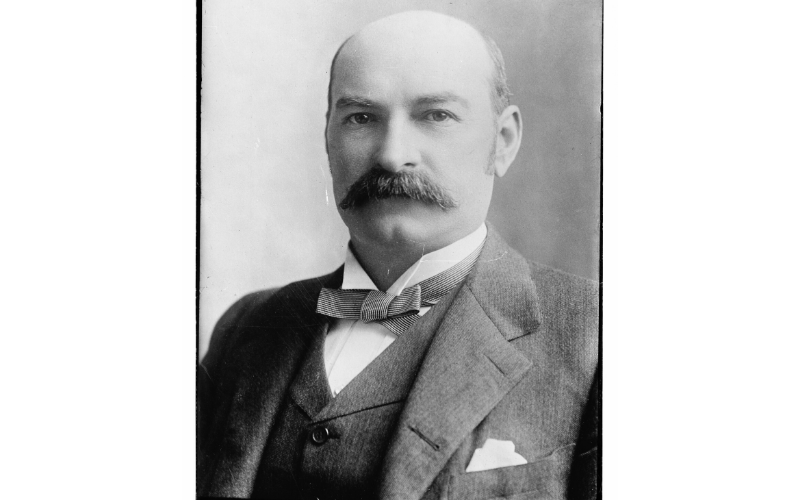

John B. McDonald.

Born in Cork in 1844, McDonald moved to the United States when he was just four years old during the Irish Famine of 1845-50.

His first venture into the New York construction trade came during the construction of the Boyd Corners Reservoir in Putnam County, New York. Although a complete novice in construction, McDonald showed a great aptitude for the trade and he learned the logistics of the industry on his first job in Upstate New York.

Read more

Soon after, he became the Inspector of Masonry for the New York Central’s Fourth Avenue Tunnel, which began construction in 1872.

It was the start of a meteoric rise for McDonald who became highly sought-after and went on to front a number of lucrative projects towards the tail end of the 1800s.

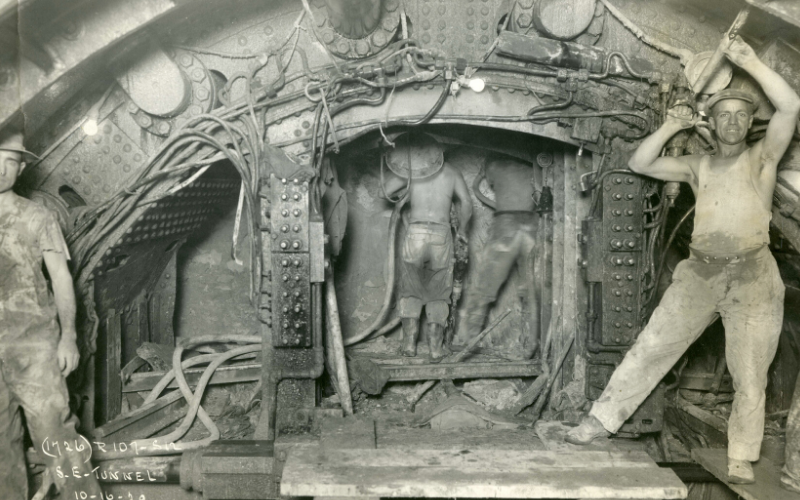

Workers on a tunnel in Greenpoint

In the 1880s, McDonald began contracting on his own, and in 1889 was hired to build the Howard Street Tunnel for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. His success on the project saw him rise to prominence within Tammany Hall - home of the Democratic machine in New York City.

Tammany Hall effectively ran New York at the time and a position of prominence was nothing to be sneered at.

Dominated by Irish immigrants, Tammany Hall found work and housing for incoming Irish ex-pats in return for their fierce loyalty at the voting ballots.

In 1900, 36% of Irish people in New York were employed by the city and by 1930s that figure had risen to a staggering 52%, a statistic which is indicative of the huge Irish influence at the turn of the 20th century.

McDonald was one of many immigrants to benefit from a political culture in which government officials, contractors and sub-contractors, and leaders of the trade unions were Irish.

Construction of a subway line on 7th Avenue, 1914

It was because of this strong political backing in Tammany Hall that McDonald won the bid for the city's first subway line, according to New York Transit Museum Curator Jodi Shapiro.

The Rapid Transit Act, signed into law in 1894, called for rapid transportation systems for cities of over one million inhabitants and led to the eventual construction of New York's world-famous subway system.

Once a team of engineers designed the system, the project was opened up to contractors and McDonald, with his close ties to Tammany, beat off his rivals to the bid.

The Irish immigrant's bid of $35 million (more than $1 billion today) wasn't even the highest bid for the project.

Andrew Onderdonk, his rival, bid $39 million to win the project but wasn't able to post the $5 million in security bonds and so the project went to McDonald.

In effect, McDonald was employed by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) to build the subway.

He was given a daunting four-year window to build one of the most complex projects in the city's history along one of its main thoroughfares.

McDonald made use of a technique called 'cut and cover' - a disruptive, yet effective, process that involved uprooting the New York streets with dynamite blasts at night.

Daytime crews would then clear away the rubble with the help of a mule cart and, when the debris was cleared, another team would build the tunnel.

When the tunnel was finished, the workers would then cover it with the displaced rubble and dirt, before laying a fresh pavement above it.

The construction was not without its issues. The grueling work took its toll and 16 workers died during the four-year construction period due to tunnel collapses and accidents.

Despite labor disputes and issues with material procurement, however, McDonald completed the nine-mile stretch of track on schedule and it was opened to the public in October 1904.

It proved to be a resounding success.

An estimated 150,000 people paid the five-cent fare to ride the subway on its inaugural day in operation and, within four years, the city's subway system stretched over 23.8 miles.

Expansion into Brooklyn followed quickly and the subway system today includes 850 miles of track and 472 stations in the five boroughs of New York.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

McDonald's exploits didn't go unnoticed and Thomas F. Ryan, head of the Metropolitan Street Railway, hired him away from the IRT in 1905.

However, numerous investigations into property rights and ownership of routes stalled his projects, and McDonald never built another subway.

McDonald was then touted to build the Panama Canal, but his part in the project never came to fruition.

McDonald died on St. Patrick's Day in 1911 and a New York Times article published after his death said: “The poor Irish lad, with little scientific culture, but taught in the school of experience, achieved where others had deliberated, hesitated, and failed even to attempt."

The article added that McDonald himself thought that the job was “Nothing more than building a string of cellars, end to end.”

Read more

* Originally published in 2020, updated in Nov 2024.

Comments