An incredible new collection of photographs in the New York Transit Museum shows how an Irish immigrant masterminded the building of the city's first subway tunnels.

The images, captured by brothers Pierre and Graville Pullis, document the construction of the huge project which began in 1900.

Aside from documenting the construction of one of the world's biggest underground railway system, the images also capture an era of transition in New York's history between 'Old New York' and the modern, urban jungle that we know today.

The images capture some of the old ways of life in early 1900s New York. Men congregate outside taverns, women push prams, children play, merchants sell their wares. In many of the photographs, workers or passers-by often look directly into the camera.

They went on display at the New York Transit Museum last week.

The construction of a line on Lexington Avenue in 1917

The city's first subway line was completed in 1904, just four years after construction began and ran along a nine-mile track from City Hall in Downtown Manhattan to 145th Street in Harlem.

The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) won the initial construction contract with a $35 million bid (over one billion dollars today) and the contract also awarded the IRT a lucrative 50-year operating lease.

John McDonald, an Irish immigrant builder, oversaw the construction of the company's (and the city's) first project in the early 1900s.

McDonald was tasked with the enormously difficult challenge of engineering the city's first underground rail line all the while avoiding the sprawling network of sewer, water, and electrical lines.

He also had to take particular care to ensure that the foundations of nearby buildings were not weakened or damaged during construction.

Building underneath the iconic fountain at Columbus Circle posed especially difficult challenges and the grueling and hastily completed work resulted in the deaths of 16 workers across the four-year construction period.

To complete the daunting task, McDonald made use of a technique called 'cut and cover' - a disruptive, yet effective, process that involved uprooting the New York streets with dynamite blasts at night.

Read more: Remembering New York City’s famous Irish immigrants this St. Patrick’s Day

Daytime crews would then clear away the rubble with the help of a mule cart and, when the debris was cleared, another team would build the tunnel.

When the tunnel was finished, the workers would then cover it with the displaced rubble and dirt, before laying a fresh pavement above it.

Despite the obvious difficulties, the construction of New York's first underground line proved to be a resounding success and 150,000 people paid the five-cent fare to ride the train on its opening day.

7th Avenue and 42nd Street 1914

With a huge early ridership and a 50-year contract, IRT expansion was inevitable and by 1908, the Manhattan underground system stretched to 23.8 miles in total.

Simultaneously, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) was enjoying a similar monopoly on the opposite side of the East River.

Both companies wanted to expand into the other's territory which led to an agreement between the city and the two companies to divide future contracts between them.

It was this agreement that saw the expansion of the subway network into all five boroughs of New York. Similarly, the agreement led to the first tunnels being built underneath the East River.

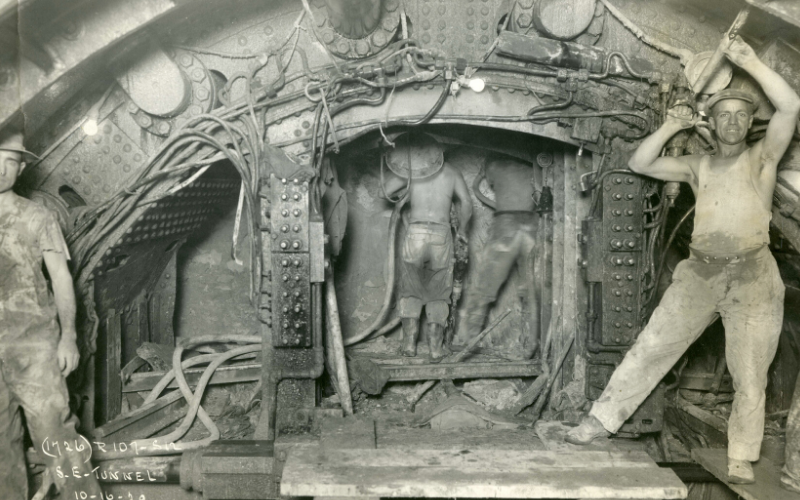

Tunneling under the river was a particularly dangerous undertaking that caused decompression sickness among several workers.

More commonly known as 'the bends', decompression sickness is an incurable illness often found among scuba divers that can cause death by stroke, heart attack or lifelong joint pain. It is usually caused by ascending to the surface too rapidly.

In addition to decompression sickness, workers had to deal with the dangers of blowouts, an unusual phenomenon that caused unfortunate workers to be sucked through a hole in the tunnel and propelled through the East River and into the air.

Workers in the Greenpoint Tube - 1929

Highly compressed air was pumped through the underwater tunnels to prevent them from collapsing under the weight and pressure of the river above. However, in the rare instance that a crack occurred in the tunnel, workers were in grave danger of being sucked up into the river.

In 1905, for instance, Marshall Mabey noticed a crack in the tunnel's surface. When Mabey and two colleagues (Frank Driver and Michael McCarthy) tried to plug it, they were torpedoed up through the riverbed and water above them before shooting up to 200 feet into the air, according to reports.

Mabey survived the ordeal, but Driver and McCarthy were not so lucky.

Their story was just one of many instances where workers risked their lives to build the subway network that we know today.

Read more: The Irish who dug the tunnels for New York’s subway system

Today, the subway stretches over 850 miles of track, has 472 stations and services more than 5.5 million people on an average weekday.

This sprawling, intertwining, and holistic network of tracks would not be possible were it not for the bravery and sacrifice of men working without the benefit of modern equipment, or without the ingenuity of a certain Irish immigrant who masterminded the inaugural track.

Comments