Editor's Note: The following is an extract from “Massacre at Duffy’s Cut: Tragedy & Conspiracy on the Pennsylvania Railroad” by William E. Watson and J. Francis Watson, the brothers behind the excavation of the mass grave at Malvern, Pennsylvania.

A description of the new book reads: “For more than 180 years, the railroad maintained that cholera was to blame and kept the historical record under lock and key. In a harrowing modern-day excavation of their mass grave, a group of academics and volunteers found evidence some of the laborers were murdered. Authors and research leaders Dr. William E. Watson and Dr. J. Francis Watson reveal the tragedy, mystery and discovery of what really happened at Duffy's Cut.”

Funds raised by the book will be used to continue funding the excavation and reinternment of the Irish immigrants remains.

Philip Duffy and Duffy’s Cut: An Immigrant Laborer Becomes a Gentleman

Irish-born railroad contractor Philip Duffy, whose name has inextricably been linked with the deaths of fifty-seven fellow Irish immigrant laborers in August 1832 at the place known as Duffy’s Cut, has been styled an “immigrant who succeeded against the odds.”

Over the years, Duffy worked his way up the business and social ladder from an immigrant laborer to a respected railroad contractor. Before his death, his occupation was listed as a “gentleman” within the city of Philadelphia. This chapter will document Duffy’s transformation from Irish laborer to gentleman.

Philip Duffy’s rental house in Willistown Township, circa 1832. (Watson Collection.)

Philip Duffy was born in Ireland in 1783, the year the Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution. Fifteen years later, in 1798, as Ireland witnessed the United Irishmen Rebellion, the fifteen-year-old Duffy joined many of his compatriots and fled Ireland for a new life in America. Duffy settled in Philadelphia County, where he and his family spent most of their lives, outside of his sojourns as a railroad contractor in different parts of the state of Pennsylvania. In 1813, with Great Britain at war with his adopted country, Duffy filed his petition for naturalization.

Read more: New Duffy’s Cut beer will fund excavation of tragic Irish railroad workers site in PA

When Duffy became a citizen of the United States, he was thirty years old. Between his arrival in 1798 and the later 1820s, Duffy moved up from working as a laborer to become a contractor who hired and supervised other laborers on public works projects. Duffy’s rise to the position of contractor coincided with the dawn of the railroad age in the United States. The first known railroad contract on which Duffy is named as a contractor dates from February 1829, where he is listed as “partner” with his brother-in-law, and fellow Irish immigrant, James Smith on “section 16” of the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad (P&C). Duffy was successful enough on that mile of the P&C that in June 1829, he received his own contract to work on mile 60 of the rail line. Newspaper accounts reported that Duffy used Irish immigrant laborers for that work, which was a practice that he would continue throughout his career on the railroad.

Skull of skeleton 006, showing axe blow and bullet hole. (Watson Collection.)

The work crew that Duffy used at mile 60 was described as “a sturdy looking band of the sons of Erin.” Some of Duffy’s Irish immigrant laborers even lived with him at times. The work along mile 60 was described as “Herculean,” as Duffy’s laborers built a very difficult roadbed for the railroad. With mile 60 of the P&C, Duffy made a name for himself as a hardworking contractor who was able to prosecute difficult work in a relatively short period of time. This became the pattern for the rest of Duffy’s life as he worked for the railroad and, later, for the City of Philadelphia. Eleven months after he began work on mile 60, Duffy was given a contract for what became the most expensive, the most difficult and the most dangerous mile of railroad on the whole line of the P&C, the mile that would come to be known as Duffy’s Cut.

Duffy’s Cut: The immigrant makes a name for himself

Duffy was presented with the contract for mile 59 of the P&C on May 18, 1831. That mile of the railroad was to be completed in less than eleven months. According to his railroad contract, Duffy was expected to complete the work on mile 59 by April 1, 1832. Because of the difficult nature of the work at Duffy’s Cut, April 1, 1832, came and went, and the work was nowhere near completion. Duffy’s original work crew was unable to complete the work of ripping apart the earth along the railroad cutting that was eventually called Duffy’s Cut, as well as the bridging of the large valley between miles 60 and 59 with the materials from the cut (which became known as Duffy’s Fill or Duffy’s Bank). Duffy was so far behind in his work by the summer of 1832 that he needed to hire a whole new work crew to finish the job. What Duffy did at Duffy’s Cut was what he did throughout his career: in June 1832, he hired a group of recently arrived Irish immigrant laborers.

Duffy’s Cut excavation team, 2009. (Watson Collection.)

Less than eight weeks after Duffy hired the fifty-seven Irish laborers, all were dead and buried in the railroad fill. In August, cholera made its way into the shanty where the Irish laborers lived, located just several yards south from their worksite. Cholera came from drinking contaminated water, but no one in 1832 knew how it was transmitted. Immigrants in 1832 were often suspected of being carriers of cholera, while it is clear from the evidence that the laborers at Duffy’s Cut actually caught the disease from a source in Chester County. The railroad records indicate that when the laborers realized that cholera had broken out in their shanty, some tried to flee to neighboring farms but were turned away by people afraid of the disease. By the end of August, all fifty-seven Irish laborers were dead.

The railroad reported that the laborers had died of cholera, and the newspapers downplayed the number of the dead throughout the nineteenth century. The archaeological dig and the anthropological examination of the remains revealed that the men and the woman recovered at the site were all murdered. Nativism along with a fear of cholera and fear of foreigners as supposed harbingers of the disease was likely responsible for vigilante violence that occurred at mile 59.

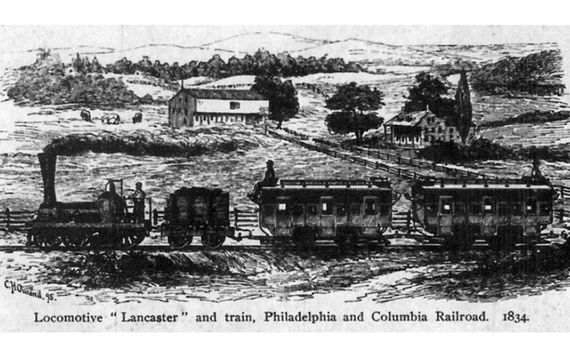

Philadelphia and Columbia locomotive Lancaster and cars, 1834. From Watkins’s History of Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

No record has been found to indicate Duffy’s frame of mind during and after the events at mile 59. Where was Duffy when his men were murdered and others died of cholera in August 1832? We may never know. What we do know is that when his fellow Irishmen were dying at Duffy’s Cut, Duffy himself was living elsewhere. He did not live in the shanty along with his newly arrived laborers; he lived in a rented home several miles away in Willistown Township, and with a separate (and safe) water source.

For more information and to purchase the book, visit duffyscut.immaculata.edu.

Comments