An excerpt from Mark Bulik’s "The Sons of Molly Maguire: The Irish Roots of America's First Labor War,"

Chapter 1: “A Slumbering Volcano”

“Subterranean spirits might dwell in burning mountains, or occupy themselves in mining . . . Many Irish legends relate to such. They may appear as Daome-Shi [fairies], dressed in green, with mischievous intent.”

— James Bonwick

The first of the assassinations came at the dawn of the year, in the middle of the day, in the shadow of a burning mountain. The last came nearly thirteen years later, on a December night as black as anthracite. Both killings involved teams of gunmen, opening fire in the home of an Irish immigrant. In many ways, the murders were mirror images of each other — the bookends of a shadowy struggle that left dozens dead in the hard-coal fields of northeastern Pennsylvania in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Those marked for death in the two attacks stood on opposite sides of that struggle. The first victim was a former militiaman whose murder was blamed on a violent secret society. The last victim was a member of that secret society and his pregnant sister-in-law. A militia unit’s second-in-command was implicated in the killings.

In neither case was anyone ever brought to justice. For generations, the exact motives have remained a mystery.

The first killing took place in a valley that was often swathed in sulfurous fumes. The fire in the burning mountain had blazed long and deep, but when exactly it erupted remains something of a mystery. One account says it all began in the darkest recesses of winter, on December 13, 1840; another claims it was 1835. Local folklore is short on specifics but long on atmosphere.

The miners were going for a vein of anthracite so thick it was known as “the jugular” near the village of Coal Castle, Pennsylvania, in the Heckscherville Valley of Schuylkill County. In 1932, an eighty-six-year-old resident of the valley told a folklorist that water trickling down into a mine had frozen, turning the underground chambers into a palace of shimmering black ice, with frozen stalactites reaching down from the roof and crystals coating the anthracite walls. The miners, so the story goes, lit a fire on a Saturday to melt the ice, then left, returning on Monday to find the shaft and the face of the coal seam ablaze. The local newspaper, relating the story decades after the fact, reported that two of the miners entered the burning pit to retrieve their tools, never to return.

Read more

While the newspaper said it was common practice to set fires in grates to prevent mine water from freezing, Scientific American blamed the blaze on “careless miners.” The phrase had very specific legal ramifications. Because carelessness by a miner — any miner, not just the dead one — could absolve a mine operator of liability for a fatal accident, “careless miner” became a stock phrase for those who would have otherwise borne the responsibility.

However and whenever it started, the underground fire burned for years, at times leaving the valley below and the hidden stream that ran through it enveloped in steam and smoke.

“It has even roasted the rocky strata above it, destroying every trace of vegetation along the line of the breast, and causing vast yawning chasms, where the earth has fallen in, from which issue hot and sulfurous fumes, as from a volcano,” one observer wrote in 1843. Elsewhere, the fire hollowed out portions of the hill. Anyone traversing those areas ran the risk of plunging through the upper crust, perhaps three or four feet, into pits of ash up to one hundred feet deep. The fire was “still burning, like a slumbering volcano,” in 1855.

By June 21, 1861, when David J. Kennedy painted a watercolor of the scene, Mine Hill Gap and Burning Mountain, there was just the barest hint of the underground fire — a bare patch and two bare trees on the mountain in the background — but there was also the suggestion of a more recent conflagration. A rifleman in blue appears along the rail line through the gap, though it is not clear whether he is a Union Army soldier on patrol or simply a hunter, out for a stroll in the lingering light of the summer solstice.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

For the Irish immigrants who dominated the valley, the underground inferno was a mixed curse. By 1858, word had spread that sulfur-laden water from the burning mine cured rheumatism, restored twisted limbs, and even rejuvenated a broken-down old colliery mule. People from far and wide made the pilgrimage to Coal Castle to cure their afflictions.

In that sense, the mine water was akin to the holy wells of Ireland that were said to effect miraculous cures, and when some enterprising miners decided to sell barrels of the stuff for profit, the older Irish of the area were aghast at the sacrilege. Holy wells were not to be profaned — indeed, it was said they could lose their powers if desecrated by a murder nearby. So perhaps the fate of the burning mine’s healing waters should come as no surprise. “The day came when their misgivings were realized,” the folklorist George Korson wrote of the Irish. “The snow no longer melted on the mountain in the winter. Its water became like any other sulfurous mine water. The magic mine had grown cold!”

Read more

It was here in the shadow of Mine Hill, where miracles were born of fire and brimstone and peasant belief clashed head-on with the capitalist spirit, that one of the century’s most sensational campaigns of cold, calculated killing began, on a winter’s day just about a quarter-century after the start of the mine fire. It was these burning hills that gave birth to the Molly Maguires of Pennsylvania.

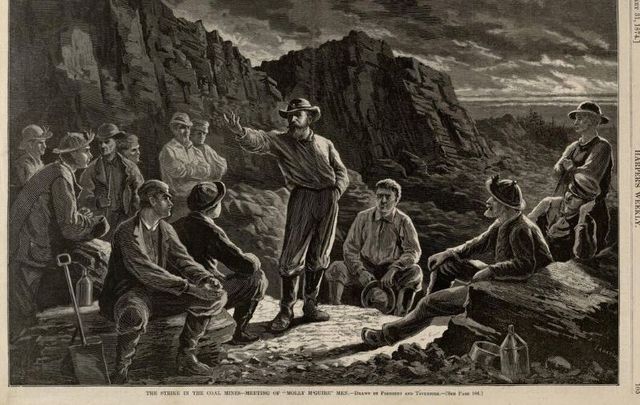

What defined a Molly Maguire was the resort to conspiratorial violence — during the potato famine in Ireland, teams of Mollies often dressed as women, had murdered grasping Irish landlords and local magistrates with ruthless efficiency. That sort of organized, premeditated violence claimed its first life in this country on January 2, 1863, in the village of Coal Castle, under that “smoldering volcano” at Mine Hill Gap.

The Mollies would gain infamy in Pennsylvania for killing mine bosses, but the man gunned down in Coal Castle that day was an Irish-born mine worker, James Bergen, a wounded Union soldier who had spent his entire life under a series of rumbling volcanoes.

Excerpt from Mark Bulik's “The Sons of Molly Maguire: The Irish Roots of America's First Labor War.” Fordham University Press, 2015.

*Originally published in 2015, updated in September 2021.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments