Editor's Note: The 1916 Easter Rising took place over the course of five days in Dublin and forever changed the course of Irish history. Writer and historian Dermot McEvoy produced 16 profiles of the Irish Rebel leaders who were executed and who, gradually, have come to be seen as heroes.

Between May 3 and 14, 1916, 15 leaders of the Rising were court-martialed by the British Army under General John Maxwell and convicted. IrishCentral looks at the leaders from James Connolly to Joseph Mary Plunkett and shares their stories.

On May 11, 1916, there were no executions, but there were two significant developments.

In Dublin, according to the Irish Times, “The following results of trials, by Field General Court-martial, were announced at the Headquarters, Irish Command, Dublin: Sentenced to death, and sentence commuted to penal servitude by the General Officer, Commander-in-Chief, Éamon de Valera, penal servitude for life.

”Across the Irish Sea, there were fireworks in the House of Commons, courtesy of John Dillon, MP of the Irish Parliamentary Party, who stood up to lambast the British over their secret court-martial and executions:

“I say I am proud of their courage, and, if you were not so dense and so stupid, as some of you English people are, you would have had these men fighting for you, and they are men worth having. ... ours is a fighting race ... The fact of the matter is that what is poisoning the mind of Ireland, and rapidly poisoning it, is the secrecy of these trials and the continuance of these executions ... enthusiasm and leadership.

“[The rebels showed] conduct beyond reproach as fighting men. I admit they were wrong; I know they were wrong, but they fought a clean fight, and they fought with superb bravery and skill, and no act of savagery or act against the usual customs of war that I know of has been brought home to any leader or any organized body of insurgents.

“[...] I do most earnestly appeal to the Prime Minister to stop these executions ... it is not murderers who are being executed; it is insurgents who have fought a clean fight, a brave fight, however misguided, and it would be a damned good thing for you if your soldiers were able to put up as good a fight as did these men in Dublin—three thousand men against twenty thousand with machine-guns and artillery [Heckled and responds] ... we have attempted to bring the masses of the Irish people into harmony with you, in this great effort at reconciliation—I say, we are entitled to every assistance from the Members of this House and this Government.”

The Last Two

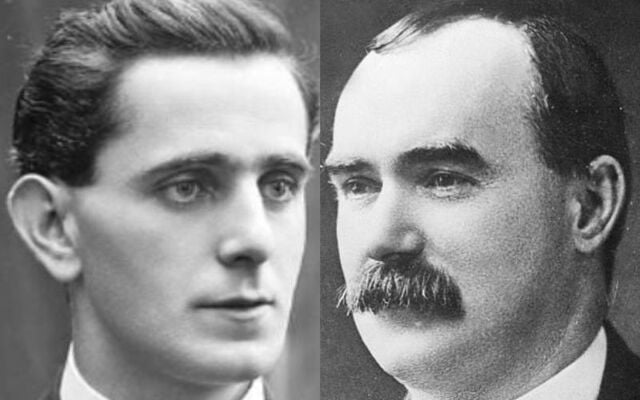

Although Dillon’s words may have saved the lives of some rebels sentenced to death, they were too late for two of the most prominent leaders, James Connolly and Seán MacDiarmada. Their fates had been already determined because both had been signatories of the Proclamation and Prime Minister Asquith had already signed off on their shootings: “There are two other persons who are under sentence of death—a sentence which has been confirmed by the General [Maxwell]—both of whom signed the Proclamation and took an active part…in the actual rebellion in Dublin…in these two cases, the extreme penalty must be paid.”

The executions of Connolly and MacDiarmada would constitute a clean sweep of those who had put their names to Ireland’s Declaration of Independence.

The Court-martials of James Connolly (Prisoner #90) and Seán MacDiarmada (Prisoner #91) at Richmond Barracks, May 9, 1916 – the two faced the same charges:

CHARGE: 1. Did an act to wit did take part in an armed rebellion and in the waging of war against His Majesty the King, such act being of such a nature as to be calculated to be prejudicial to the Defence to the Realm and being done with the intention and for the purpose of assisting the enemy”

2. “Did attempt to cause dissatisfaction among the civilian population of His Majesty”

PLEA: Not Guilty (both charges)

(The members of the court and witnesses were duly sworn in)

VERDICT: Guilty. Death (first charge): Not guilty (second charge)

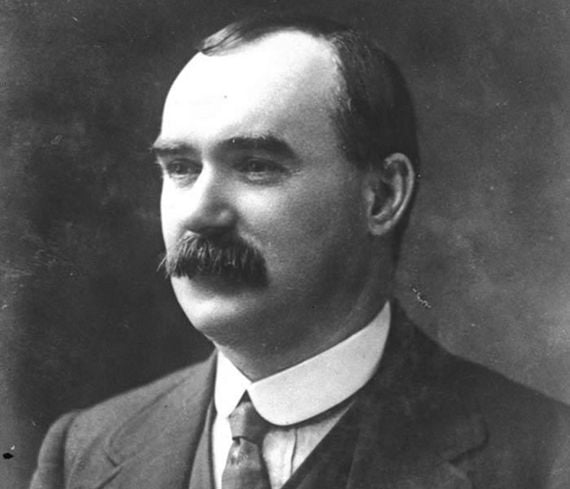

James Connolly.

Epilogue

May 12 marked the last day, for now, of the execution of rebel leaders. In the space of nine days, the British had shot 15 insurgents—but they were not done yet. They still had one more to go—Sir Roger Casement, who would be hanged in London on August 3.

After the execution of the seven signatories of the Proclamation, the theme of “blood seeping from under a closed door” becomes prevalent among the Irish people. The British, in making their point that they would not stand for any more insurrection in Ireland, woke up the deep nationalism that dwells in every Irishman’s heart. The shootings guaranteed that Ireland would be a bloodbath for the next six years.

The only clear reason that can be given for any of the remaining non-signatory executions is revenge. Willie Pearse had basically nothing to do with the planning of the Rising and only held the rank of Staff Captain in the Irish Volunteers (the same rank as Michael Collins). The only reason he was shot was because he was the brother of Padraig.

John MacBride was also a revenge killing. He was shot because he had been a consistent thorn in the side of the British for over 20 years, going all the way back to the Boer War. He only joined the battle on Easter Monday when he accidentally ran into the Volunteers assembling on St. Stephen’s Green when he was on his way to his brother’s wedding reception. Also, the garrison at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory saw less action than almost any other outpost, so the order of execution had nothing to do with British casualties.

The execution of Seán Heuston was certainly a revenge shooting. It seemed that the British were embarrassed that he had out-soldiered them at the Mendicity Institution.

Con Colbert’s death is one of the oddest in that he wasn’t even in charge of the garrison at Marrowbone Lane.

Ned Daly, by all accounts, both Irish and English, did a brilliant military job at the Four Courts and environs. He caused many casualties among the British, but he and his men fought a clean fight. His biggest sin may have been that he was Thomas Clarke’s brother-in-law.

Micheál O’Hanrahan was the titular second-in-command at Jacob’s, but Major John MacBride was really in charge militarily. Also, this was one of the quietest outposts during Easter Week.

Thomas Kent in Cork was defending himself and his family from an onslaught by the RIC in Cork. He was not even active on Easter Monday as Cork remained quiet.

Michael Mallin was in charge of a small force at the College of Surgeons and St. Stephen’s Green but was not spectacularly successful as a military commander.

Roger Casement’s execution by rope was also a revenge killing because of what he symbolized—the utter hypocrisy of the British Empire. He had revealed them for what they were—exploiters of other people’s treasures.

What most of these men had in common is that they were known by the Special Branch detectives of the G-Division, the Intelligence Division, of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. All were picked out because they were known for their activities in the Irish Volunteers. This fact was not lost on Michael Collins. When Collins returned to Dublin from imprisonment in Wales, he made two things his top priorities: 1) Intelligence gathering; and 2) putting together an Active Service Unit—the Squad, AKA, “The Twelve Apostles”—to take care of Intelligence matters. This eventually led to Bloody Sunday 1920 when Collins’ Squad executed 14 British Secret Service agents in one morning. In the end, Collins’ intelligence-gathering was superior to that of the British Empire.

General Maxwell’s brag—“I am going to ensure that there will be no treason whispered for 100 years”—had turned into a match and with that match, he would light the fuse which would blast Britain out of most of Ireland after 700 years.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising" and "Irish Miscellany: Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Ireland." He may be reached at [email protected] and you can follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook here.

*Originally published in 2016, updated in May 2025.

Comments