To commemorate the anniversary of the Easter Rising, writer and historian Dermot McEvoy produced 16 profiles of the Irish Rebel leaders who were executed and who, gradually, have come to be seen as heroes.

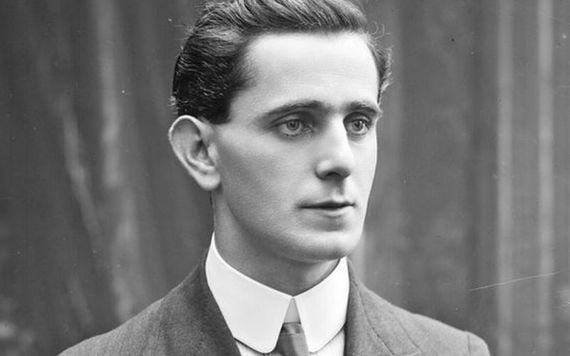

Seán MacDiarmada

Seán MacDiarmada was born in County Leitrim in 1884. He left home at a young age and traveled to Edinburgh and Belfast where he held many jobs, from tram conductor to barman. At 22, he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and set out on his lifelong quest to drive the English from Ireland. When Tom Clarke returned from America in 1907 and teamed up with MacDiarmada, Ireland finally had her own Dynamic Fenian Duo, two men capable of rousing Ireland out of its political coma.

MacDiarmada, like his young protégé Michael Collins, was handsome and charismatic, had an ebullient personality, and was a master organizer. He traveled the country, bringing the word of the new Ireland, an Ireland that would no longer bend its knee to the British. Even an attack of polio in 1912, which left him lame, could not contain his enthusiasm.

In mid-1915, he was arrested under the Defence of the Realm Act for trying to subvert British recruiting for the Great War and was duly packed off to Mountjoy Gaol for several months. Tom Clarke was delighted, as he wrote to Joseph McGarrity in America: “The government made a great capture last Sunday week – a fellow named McDermott,” Clarke writes. “He is one of those bloodthirsty, good for nothing thunder and turf fellows who is always spouting sedition and who at one time ran a rag I think he called it Freedom. Well, this lad went down to Tuam and there commenced to give out against our glorious Empire.”

When England went to war with Germany, MacDiarmada knew it was Ireland’s time. His prime purpose was to resuscitate Irish nationalism, which he feared was dying. He knew the only way to do this was to stage a rebellion. “If we hold Ireland for a week,” he said, “we will save Ireland’s soul.”

In the months leading up to the Rising he was an integral part of the IRB’s Military Council, which was planning the uprising. On Easter Monday, because of his lameness, he arrived, along with Clarke, at the GPO via automobile. What they had been working towards for so long had finally come to fruition. “One of my happiest recollections of Easter Week,” said Diarmuid Lynch, “was that of Seán MacDermott and Thomas Clarke sitting on the edge of the mails platform beaming satisfaction and expressing congratulations.”

As the week went on MacDiarmada took more control of the GPO as Connolly was wounded, Plunkett was ill, and Pearse was in a funk. With the rest of the men he made his way to Moore Street. After Pearse signed the unconditional surrender the Volunteers revolted – they would not surrender. No one, including Michael Collins, could calm the rebels.

Finally, MacDiarmada spoke up: “[You] fought a gallant fight,” he said, according to Joe Good in 'Enchanted by Dreams.' “The thing that you must do, all of you, is to survive!... We, who will be shot, will die happy – knowing that there are still plenty of you around who will finish the job.” The rebels heeded MacDiarmada’s advice and surrendered. “That quiet speech,” said Good, “was the most potent that I was privileged to hear.”

Later, Michael Collins would write of his time in the GPO and the men he admired most: “I think chiefly of Tom Clarke and MacDiarmada. Both built on the best foundations. Ireland will not see another Seán MacDiarmada.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Lagging behind on their forced march from the Rotunda to Richmond Barracks, MacDiarmada arrived almost an hour after the rest of the rebels. The sorting of rebels, according to importance, began. It may have been at this time that there was some confusion regarding MacDiarmada. He had signed the Proclamation as “Seán MacDiarmada,” but the intelligence agents of the G-Division of the Dublin Metropolitan Police knew him by the Anglicized name of “John MacDermott.” Were they one and the same? It took the DMP a while to figure it out, but in the end, they got it right.

Future Irish President Seán T. O’Kelly saw MacDiarmada “in a group assembled for deportation, with bright muffler, talking eagerly and gaily. They were lined up for inspection by detectives. The inspector stood in front of MacDermott for thirty seconds, then [he] was ordered out of the ranks and marched back to his room in the barracks.”

Liam O’Briain observed a most touching interaction in Richmond Barracks between Clarke and his protégé, MacDiarmada: “Seán fell asleep with his head on Tom’s chest…I don’t think Tom slept at all. Seán would start a little and we would hear a mutter from him saying: ‘The fire! The fire! Get the men out!’ Then you would hear Tom’s quiet voice saying gently: ‘Quiet Seán, we’re in the Barracks now. We’re prisoners now, Seán.’ ”

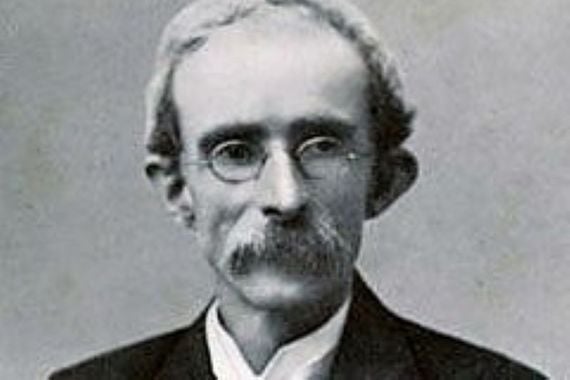

Thomas Clarke teamed up with MacDiarmada to "rouse Ireland out of its political coma"

The early shootings were the blood sacrifice that MacDiarmada thought would shake Ireland out of her political slumber: “[The executed leaders] are our victory. Had they [the British authorities] not shot them, we would be presented as a lot of poltroons who dared challenge the power of England. I’ll be shot and I hope I will be.”

He was even blunter to Desmond Ryan: “I am going to be shot. If I am not shot, all this is worthless.”

Because he was one of the last to be executed, MacDiarmada had a chance to write letters. He wrote to the old Fenian John Daly that he had been “sentenced to a soldier’s death…I have nothing to say about this only that I look on it as a part of the day’s work. We die that the Irish nation may live. Our blood will rebaptize and reinvigorate the old land. Knowing this it is superfluous to say how happy I feel. I know now what I have always felt – that the Irish nation can never die…posterity will judge us aright from the effects of our action.”

MacDiarmada also wrote to his brother and sister the day before his death: “I have been tried by court-martial and sentenced to death – to die the death of a soldier…I feel happiness the like of which I never experienced in my life before, and a feeling that I could not describe…You ought to envy me.”

At midnight his girlfriend Min Ryan – who would later marry General Richard Mulcahy – and three friends were led to Seán’s cell and remained there for three hours. Min said that Seán was “very anxious to have the others go” so they could be together alone. But it was not to be. They all left together. At 3:45 MacDiarmada was executed.

Min Ryan late wrote: “At four o’clock on that Friday morning a gentle rain began to fall. I remember feeling that at last there was some harmony in nature. These were assuredly the tears of my Dark Rosaleen over one of her most beloved sons.”

* Originally published in 2016, last updated in April 2023.

~~~~~~~~~

Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website and Facebook page.

Comments