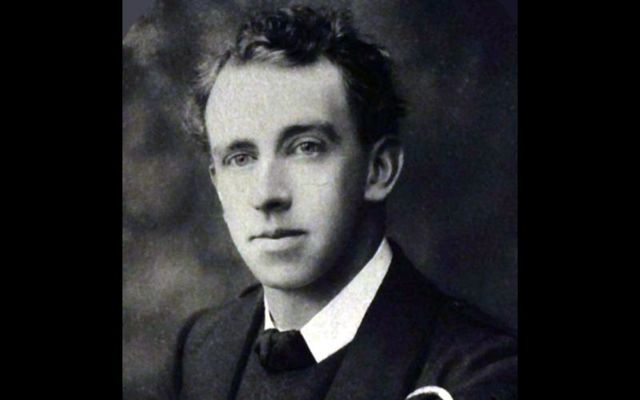

Thomas MacDonagh was born in Cloughjordan, Co. Tipperary in 1878 and trained as a teacher before becoming a celebrated poet, playwright and leader in the Irish Volunteers. He played a central role in the 1916 Easter Rising and was executed in 1916 at the age of 38 leaving a legacy of cultural and political influence that endures today.

Below, Dermot McEvoy takes an in-depth look at the life of Thomas MacDonagh and his contribution to Irish history:

Thomas MacDonagh was born in County Tipperary in 1878, the son of two schoolteachers. In 1902, he joined the Gaelic League, which began his intense interest in Irish nationalism. In 1913, he joined the Irish Volunteers and was appointed Commandant of the entire Dublin Brigade and Director-General of Training.

He was an intellectual with an M.A. from University College Dublin. He had taught with Pearse at St. Enda’s and had been a prodigious writer and poet. His son Donagh remembered him leading: “…a peaceful and regular life at the beginning of the First World War. Happily married, surrounded by his friends, and his books, a friend to artist and scholar, he was, as Yeats said, ‘coming into his force.’”

During Easter Week, he was in charge of Jacob’s Biscuit Factory (now the Technological University Dublin) at Bishop and Aungier Streets. Although beloved by his men, he wasn’t much of a soldier. He had run into Major John MacBride while mustering his troops at St, Stephen’s Green, and MacBride was soon running things inside Jacob’s.

Of all the outposts taken by the rebels, Jacob’s saw the least action. After Nurse O’Farrell brought Pearse’s terms of surrender to him MacDonagh met with General Lowe and decided to surrender his station. “They might shoot some of us,” he told the Volunteers, “they can’t shoot all of us.” The troops rose up in revolt and were only quieted by the words of MacBride. MacDonagh and MacBride then marched the troops to St. Patrick’s Park where they surrendered to Lowe.

At his court-martial MacDonagh remained mute until the end where he said he “did everything I could to assist the officers in the matter of the Surrender, telling them where the arms and ammunition were after the surrender was decided upon.”

Reflecting on this statement, he wrote in a letter to his wife just before he was executed: “At my court-martial in rebutting some trifling evidence I made a statement…On hearing it read after, it struck me that it might sound like an appeal. It was not such. I made no appeal, no recantation, no apology for my acts. In what I said I merely claimed that I acted honorably and thoroughly in all that I set myself to do…In all my acts…I have been actuated by one motive only, the love of my country, the desire to make her a sovereign independent state. I am ready to die and I think God that I die in such a holy cause.”

Father Aloysius from Church Street stated: “I heard the Confessions of Pearse and MacDonagh and gave them both Holy Communion. They received the Blessed Sacrament with intense devotion and spent the time at their disposal in prayer. They were happy – no trace of fear or anxiety.”

After Pearse was executed, MacDonagh was next. A British soldier said: “They all died well, but MacDonagh died like a prince.”

But tragedy would continue to haunt the MacDonagh family, even after Thomas’ death. He was married to Muriel, one of the highly nationalistic Gifford sisters. He was brother-in-law to Joseph Plunkett, who married Grace Gifford.

Muriel converted to Catholicism and on the first anniversary of her husband’s death and received her First Holy Communion.

In the summer of 1917, the widows and families of several of the 1916 martyrs were sent on a seaside holiday to Skerries, County Dublin sponsored by the Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependents Fund, which was administered by Michael Collins. On July 9, Muriel went swimming, got into difficulty, and drowned.

According to Anne Clare in her book about the Gifford sisters, "Unlikely Rebels," “[The MacDonagh children] were collecting shells on the beach with their Aunt Grace when she noticed that her sister was in difficulty.

"She frantically alerted a boat’s crew to the danger, and Jimmy O’Dea, the Dublin comedian, was among those who rushed, unsuccessfully, to help, but, too late, they succeeded only in retrieving Muriel’s lifeless body.

"The first of the Gifford girls to marry, she was now the first to die.” Her two children were subsequently raised by the MacDonagh family.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at dermotmcevoy50@gmail.com. Follow him on his website and Facebook page.

* Originally published in 2016. Updated in 2026.

Comments