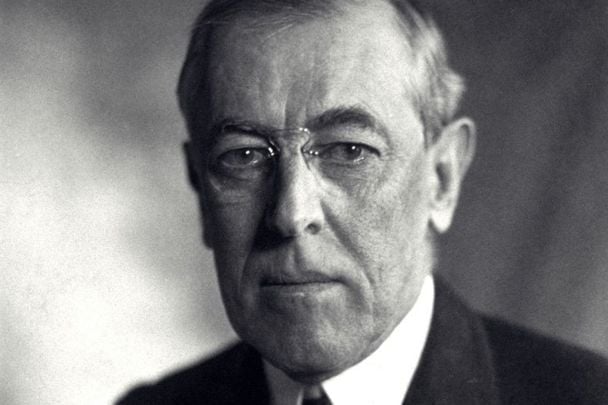

Recent protests shone a spotlight on President Woodrow Wilson’s prejudice towards African Americans. An examination of his papers also reveals a president who cared little about the Irish Question and a person who developed a distaste for the Irish in general at a critical time. Wilson served from 1913 to 1921.

In 1918, the president’s closest advisor at the time, Colonel Edward M. House, made a diary entry that reveals Wilson’s true self. “In speaking of the Irish he surprised me by saying that he did not intend to appoint another Irishman to anything; that they were untrustworthy and uncertain. He thought Tumulty (his secretary) was the only one he had come in contact with who was.”

But as a candidate and as U.S. president, Wilson was politically cunning in approaching the American Irish. He realized that offending a loyal constituency of the Democratic Party could cost him votes—and power.

In front of big-city audiences, Wilson proudly pointed to his ancestry—two paternal grandparents came from County Tyrone—to appeal to Irish Americans. For instance, less than a month before he won his first White House term in 1912, he spoke at a campaign rally at the armory of “the Fighting Irish Seventh Regiment” in Chicago.

“I have in me a very interesting and troublesome mixture of bloods,” he declared. “I get all my stubbornness from the Scotch [on his mother’s side], and then there is something else that gives me a great deal of trouble, which I attribute to the Irish. At any rate, it makes me love a scrap; and so I knew that if I was to be privileged to speak in this armory, I would be forgiven for speaking in a somewhat militant manner.”

Congenital combativeness established, Wilson applauds “the great liberty-loving men and women from every civilized country on the globe,” including “the great Irish people,” who immigrated to the U.S. From a statement like this, someone might think that he’d look favorably on the more “militant” of the fighting Irish in Ireland. That, though, wasn’t the case.

The Wilson Papers in the Library of Congress reveal that the Easter Rising and the case of Irish nationalist Roger Casement generated numerous telegrams and letters seeking presidential involvement. In fact, the day before Padraig Pearse surrendered on April 29, 1916, American attorney Michael Francis Doyle, who was helping Casement, wired Wilson, requesting a meeting about Casement and “if possible to enlist your interest on his behalf on the grounds of humanity.”

On May 2, Wilson wrote his secretary, Joseph Tumulty, rather than Doyle: “We have no choice in a matter of this sort. It is absolutely necessary to say that I could take no action of any kind regarding it.”

Those words would seem to close every door; however, Tumulty, an Irish Catholic, handed off the matter to the State Department and, subsequently, drafted a form response, making Wilson appear different from what he wrote to his secretary. On July 3, with concern for Casement’s fate growing in Congress and among the public, Tumulty instructed the White House secretarial staff to send “the following form reply under his signature” to those inquiring about the humanitarian-turned-republican.

“The President wishes me to acknowledge receipt [of] your telegram in the case of Sir Roger Casement and requests me to say that he will seek the earliest opportunity to discuss this matter with the Secretary of State. Of course he will give the suggestion you make the consideration which its great importance merits.” Though not specific about “the suggestion,” the message reflects an open-minded willingness to deal with the case. But it was really all a façade.

When Tumulty gave Wilson a message Doyle sent from London about Casement’s trial, which said “a personal request from the President will save his life,” the president in his reaction of July 20 was even more emphatic than he was on May 2. The handwritten response reads: “It would be inexcusable for me to touch this. It w’d [would] involve serious international embarrassment.”

Wilson’s hands-off approach to intervening on behalf of Casement foreshadows his refusal to introduce Ireland as a subject at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Though he played his Irish card to win political acceptance, he stopped at lip-service when faced with a life-or-death decision or a major policy initiative.

During his inaugural address as president of Princeton University in 1902, Wilson asserted: “We are not put into this world to sit still and know; we are put into it to act.” On Ireland and Irish issues, Woodrow Wilson consistently avoided action.

Though he did nothing of consequence, he kept up his act of concern throughout his presidency. In January of 1918, he had a meeting with Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, the Irish nationalist, pacifist, suffragette—and widow of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, a journalist, who was gunned down by a British officer during the Easter Rising.

Given her background, it is puzzling why Wilson was willing to see her. Her principal objective was to deliver a petition from Cumann na mBan, the Irish women’s republican paramilitary organization. The document, which somehow reached Sheehy-Skeffington without being stopped by British censors in Ireland, “put forth the claim of Ireland for self-determination, and appealed to President Wilson to include Ireland among the Small Nations for whose freedom America was fighting.”

In her account of the session, she takes pride in being “the first Irish exile and the first Sinn Féiner to enter the White House, and the first to wear there the badge of the Irish Republic, which I took care to pin in my coat before I went.” However, what is most striking is her faith that Wilson will pursue a solution to the Irish Question at the post-armistice Peace Conference.

In her memoir, "Impressions of Sinn Féin in America," she writes: “President Wilson is not the type that will lead, pioneer-like, a forlorn hope, or stake all on a desperate enterprise; but, on the other hand, he is one who by tradition (he has Irish blood in his veins) and by temperament, will see the need of self-determination for Ireland as well as for other nations. There will be sufficient pressure at home to keep the Irish question well in the forefront, and ‘if only Ireland shews herself strongly for this solution,’ President Wilson cannot turn a deaf ear.”

Her faith was misplaced.

Wilson vents pent-up anger in his statement quoted earlier about the Irish being untrustworthy some of which might derive from the efforts of members of Congress and others pushing for assistance on behalf of Ireland. Whatever the motivation, it is telling that a president would express a generalization of this kind about an entire ethnic group, one to which he had politically appealed on ancestral grounds in the past.

Even more significant is Wilson’s interpretation for who was responsible for dashing his dreams to re-make a world through the League of Nations he had worked so hard to shape. Included in a volume of his published papers is a letter from William Edward Dodd about a meeting the University of Chicago historian and future ambassador to Germany had with Wilson in early 1921. Dodd, a friend and Wilson biographer, remarks at the beginning “the President is sure a broken man.”

Continuing to describe the session, Dodd reports the president’s “insistence the Irish had wrecked his whole program for adoption of the work at Paris.” Gone is any attempt to cushion personal opinion with diplomatic language: “‘Oh, the foolish Irish,’” he would say. “‘Would to God they might all have gone back home,’” was another sentence.

For too long as president, Wilson refused to concentrate on the Irish question. Despite the leadership he tried to exert on the world stage and the radical changes within Ireland after the Easter Rising that deserved his attention, he kept ducking and dodging in public while fuming and fulminating in private. Over time, he appeared weak and indecisive.

Public opinion in the U.S. and elsewhere crystallized that Wilson was not inclined to do anything for Ireland. Though he blamed the American Irish for the failure to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and involve the United States in the League of Nations, they, in turn, blamed him for abandoning Ireland at a critical time. They had every reason to think as they did.

*Robert Schmuhl is Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Chair of American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame and author of "Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising" (Oxford University Press). This article is adapted from the chapter about Woodrow Wilson.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments