Many mixed-race Irish people who grew up in Mother and Baby homes are still looking for answers about their families and their heritage.

In the middle of the 20th century, thousands of students from African countries traveled to Ireland to study at universities such as Trinity College and University College Dublin.

During the 1960s, the Irish government created programs supporting African students in learning skills that would help them build up their newly independent states. Many of these students came from countries where there were strong links with Irish missionaries, like Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa. By 1962, around one tenth of Ireland's student population was African.

Some of the students had relationships with Irish women, who had their children outside of marriage as it would have been rare that an interracial relationship would lead to marriage in the prevailing culture. These children were placed in Ireland’s mother and baby homes and were either later adopted or transferred to orphanages.

In the recent piece "The hidden story of African-Irish children," the BBC features the stories of three of these children, now adults, who are still searching for their families decades on.

Conrad Bryan

Conrad Bryan spent his early life in the Church-run, state-funded St. Patrick’s Mother and Baby Home on the Navan Road and grew up in an orphanage.

Born in Dublin in 1964 to an unmarried Irish mother and a father who came to Ireland to study, he was told by the nuns at the home that his father was from Nigeria and his surname was Koza, but they couldn't tell him anything else.

Growing up in 1970s Ireland, Bryan knew little about Africa except what he learned from the television, or from the stories about the black children pictured on the charity boxes people would give money to during Lent.

When a missionary priest who had been in Nigeria visited the orphanage, he spoke to Bryan, who was fascinated by his stories of Nigerian tribes. The priest told him his father may have been a student in Ireland.

When he got older, Bryan left Ireland for London. He said he got a lot of surprised looks when he told people he was from Ireland.

"Being constantly reminded that you're not Irish is painful," he says. "I really struggled with that. I didn't know what my background was.

In his 20s he decided to look for his family. A nun at the orphanage contacted an Irish social worker, who got him access to personal records and contacted his mother for more information.

After a long five-year search, Bryan discovered his father's full name was Dr Conrad Kanda Koza and he was South African not Nigerian

"That was a huge shock. I look back on it and think, 'What a lie I had been living.'"

After more digging, he discovered his father had passed away in London many years previously, but Bryan was able to get in touch with his father’s family, who welcomed him warmly.

“They looked at a photograph and they claimed me straight away. It was a great affirmation of who I am, and who I should have known I was."

His father's sister visited him in London and gave him items that had once belonged to his father, including his student card from the RCSI, and a letter he had written to his family in Zulu while living in Ireland.

Byran, an accountant and auditor, has kept up with the family in South Africa and has visited often. He even went there for his honeymoon.

"I missed so much growing up," he says. "It's not just about your father, it's about your roots - your cousins, your uncles.

Bryan, who learned a lot from his experience, is now helping others like him find their families.

"People are so lost. It's part of the shocking story of lost identity and the shame of having a black father."

Credit: Getty Images

Jude

Jude, 79, is a tailor and anti-racism campaigner who also spent his early life in St. Patrick’s Mother and Baby Home.

Born in 1941 to an unmarried machinist, he would later be told his father was from Trinidad

Jude, who spent his childhood in institutions, says that growing up he rarely saw another black person.

"You'd wonder why you weren't like all the others. There would be no explanation, and I'd be embarrassed."

He trained as a tailor in his teens and went to work in Dublin. He says that he was often passed over for certain positions at work and in the beginning, some customers in the shop would avoid interacting with him.

"They'd see me and they would freeze. Some would say, 'Ah I think I'm in the wrong place.'"

As customers grew to trust him, he set up his own tailoring business. In the 1980s, Jude became of the founding members of one of the first anti-racism organizations in Ireland. He felt a sense of belonging when people of African descent greeted him on the street. However, his own searches about his heritage continued to be fruitless.

When his first son was born, Jude wanted to share the good news, but he was hit with the realization that had no family members to tell, just a few friends. When his son grew older and had to make a family tree for school, Jude says he felt shame that he could not help his son and tell him his roots.

"There is nobody you can say is a relation of yours,” he says.

Jude decided to contact Irish authorities, through which he found out his mother’s name, occupation and the country she was from. However, he couldn’t find any information about his father.

He is now being helped in his search by Conrad.

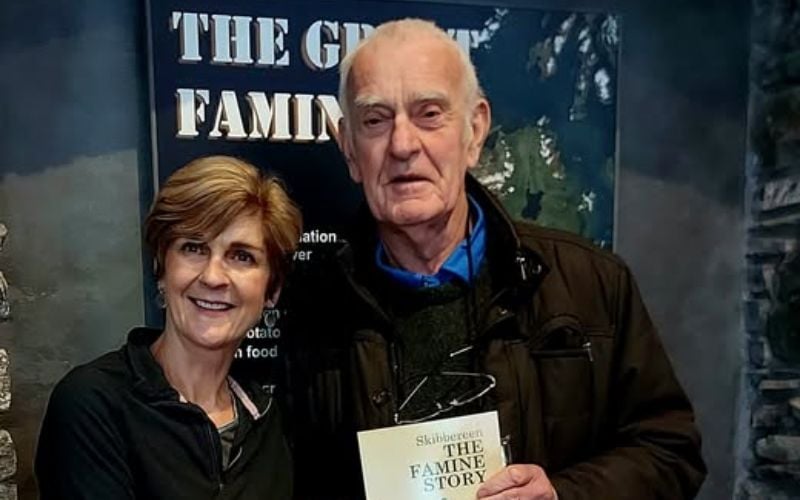

Conrad helped Jude find more information on his background through Ancestry.com, including the town his mother was from. Conrad and Jude were also surprised to discover they were distant cousins on their mother’s side.

They worked with a genetic genealogist to find out more about Jude’s father. DNA testing revealed that Jude’s father is most likely Nigerian. After searching for DNA relatives, Jude has been able to track down a distant cousin who may help him find more answers.

Marguerite

Marguerite Penrose was born in 1974 and spent three years in St Patrick’s mother and baby home.

Unlike Conrad and Jude, Marguerite was fostered and then adopted by a family in Dublin. She had a happy childhood and was grew up surrounded by a supportive family.

As she got older, she became aware of how different she was from everyone around her. She also had to have many operations for congenital scoliosis, leaving her frustrated that she didn’t know her family medical history.

"It's another complete part of your genetics that you know nothing about. As you get older, it's very important to know if there's heart disease, cancer in your family."

When her adoption was finalized, her family did receive some background information, such as Marguerite’s natural mother’s surname and when she came from, and that her natural father was a cadet from Zambia, although his name was not included.

She has since started the process with social workers to find out more information on both her natural parents.

"To get the answers to the millions of questions that spill around your head, it would mean the world."

***

Memorial at the Tuam Mother and Baby Home. Credit: RollingNews.ie

Both Jude and Conrad are members of the Association of Mixed-Race Irish (AMRI), which has lobbied the government to examine the specific experiences of mixed-race people in Mother and Baby Homes.

Due to the work of the organization, the Irish government agreed to insert a clause requiring the Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation, began in 2015, to identify cases of racial discrimination in the homes.

Conrad and Jude, along with many others, have submitted evidence about their experiences.

"We're telling our stories in the hope that the state will learn from this. In the hope of protecting the diverse minorities we have got now," Conrad told the BBC.

Jude said he thinks the government should provide funding and training for researchers to help people like him find their African origins.

"Denial of our background left a big void in a lot of people's lives. Some are terribly damaged by what they went through."

According to the BBC, the commission's final report, which will include survivor testimonies and a social history of the homes from 1922-1998, will be published soon.

Comments