Corkman Tony Mullane’s Major League Baseball record is universally accepted as being one of the greatest in the history of the sport. Yet almost a century after his retirement, he has still to be inducted into baseball’s illustrious Hall of Fame.

The legendary 19th-century pitcher remains in the top 30 on the all-time Major League win list, with a historic first American Association ‘no-hitter’ to his name to boot in 1892. Though perhaps his best-known feat was in becoming the first player to pitch with different arms in the same game.

But with no inductees being considered for Cooperstown this year - selection committees have been unable to meet to choose the class of 2021 because of health restrictions in the US - Mullane is no closer to achieving that final career honour. His personality just doesn’t fit the bill.

Mullane’s problems off the field, including accusations of racism, assault, marital violence, and unproven match-fixing allegations, marred the legacy of a sporting great whose achievements on the mound outshone even those of Babe Ruth.

The Corkman’s career total of 284 wins over the course of 13 years put him “second all-time in wins among pitchers not in the Hall of Fame,” according to a detailed article by baseball writer Jerry Grillo for the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR).

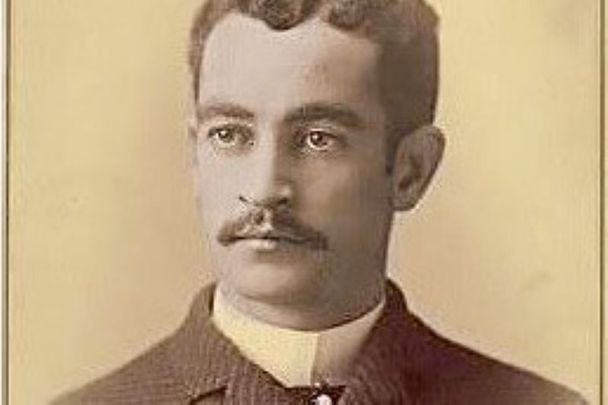

Mullane’s name may not be too widely known in Cork these days – but at the turn of the 20th century, he was one of the most famous figures in American sport. He was also one of the best-known faces.

Grillo went on to write of Mullane’s “incomparable career as one of the 19th century’s dominant pitchers and great characters, a handsome, free-spirited rogue and one of the game’s most versatile characters."

It was his versatility that brought him his fame – in July 18 of 1882 he became “the first ambidextrous pitcher in Major League history,” pitching both right- and left-arm in the same game for the Louisville Eclipse at Baltimore; a feat only repeated twice in the 139 years since. He also pitched the first no-hitter in American Association history – in September of that same season at the home of the Cincinnati Red Stockings.

Baseball writer Ray Birch, in another article for the SABR, wrote that: “Anthony John Mullane, also known by the nicknames ‘The Count’ and ‘The Apollo on the Box’, was born on January 30, 1859, in Co Cork. Well known as a ladies’ man, he was also a competitive roller skater and ice skater.

“Mullane played every position except catcher at one time or another. He was also a fine boxer, known for putting his pugilistic skills to the test on a ballfield," Birch wrote. "There is no record of whether his right cross was better than his left hook, however.”

Mullane was the oldest son of Denis Mullane, a labourer born in 1827, and Elizabeth (Behan) Mullane (born 1828), a homemaker. Anthony had two brothers and a sister, and in 1862 the family emigrated to the United States.

In his book A Fine-Looking Lot of Ball-Tossers, Richard McBane wrote that, while living in Erie, Pennsylvania, Mullane “would run away from home and play ball. He wouldn’t learn a trade. He imagined he was cut out as a ballplayer and he undoubtedly was."

In the early part of his career, Mullane’s good looks were credited in part with bringing many women to the game of baseball – so striking was the Corkman that several Major League teams planned their Ladies’ Days, a new phenomenon in the 1880s, around when Mullane would be part of the visiting teams. He was the face of baseball for a time.

Perhaps his most famous moment came in Baltimore in 1882 though. Having started the game, Mullane found himself seven runs down and increasingly frustrated. So he did what no one had seen before in the Major Leagues – he switched to his left arm. (He eventually lost the game narrowly by 9-8).

In his article entitled July 18, 1882: Tony Mullane Goes Both Ways, Grillo wrote: “A strong-armed pitcher who completed 468 of the 504 games he started, Mullane had injured his arm in a distance-throwing contest a few years earlier, so he’d thought himself to throw left-handed. That’s why he was capable of giving his self-made sinistrality a test run.”

The question, then, is why he isn’t in the Hall of Fame more than a century after hanging up his specially-designed two-handed glove. The answer, simply put, is down to his personality.

While his reputation as a ladies' man and his lauded pitching skills helped to make him a household name, it was Mullane's roguishness that brought him to notoriety, which came firstly through his handsomeness, but then more detrimentally through his consistent fallings out with the law and baseball authorities throughout his career – as well as with owners, fans, managers, and team-mates.

“Mullane became sought after,” wrote Birch of Mullane’s 1884 signing with Toledo, the latest in a long line of moves he made over a career that saw him play with more than a dozen teams. “One of Mullane’s catchers in Toledo was Moses Fletcher Walker, who is credited by some as the first African-American to play Major League Baseball.”

“Moses Fleetwood Walker was the best catcher I ever worked with,” Mullane himself would say some years later, “but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him, I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking for signals. The rest of the season he caught anything I threw – I pitched without him knowing what was coming.”

“While pitching in a game in St Louis on May 4, Mullane felt the wrath of the crowd. He was called a contract breaker and a cheat and was hissed when he hit and raucously cheered when he struck put. To the crowd’s disappointment, Mullane showed little or no reaction,” wrote Birch.

“Mullane signed with Cincinnati in November, but his signing violated a previous deal he had made with the St Louis Browns. Mullane was subsequently suspended for a year and fined $1,000 for breaching his contract with Toledo.

“Mullane signed with the Reds in 1886, opening a pool room in Cincinnati, but controversy erupted in his first season when the Cincinnati Times-Star reported an accusation that Mullane and four other players had thrown a game at Brooklyn.

“The accuser, Patrick J McMahon, alleged that Mullane told him to bet as much as he could on Brooklyn to win after the fourth, fifth, and sixth innings, despite the fact that Cincinnati was 7-0 ahead at the end of the seventh inning. With Mullane pitching, Brooklyn scored eight runs in the eighth and four more in the ninth to win the game.

“The Brooklyn club was connected to some New York gambling houses with which Mullane was alleged to have made a bargain. Mullane sued the newspaper in Ohio superior court over what he deemed to be slanderous and malicious libel. Meanwhile, a baseball panel cleared Mullane of any charges.”

Mullane fell out with the team owners not long after that – he was suspended without pay and fined $100 for insubordination after refusing to play until his salary was increased. The situation became “more complicated when Mullane threatened the president of the club, Aaron Stern, with violence over the fine."

“The 1888 season was relatively uneventful for Mullane”, wrote Birch, “although in August he was arrested at Brooklyn ballpark on a charge of contempt for failure to appear regarding a charge of not paying for some whiskey, but eventually paid his bill and the matter was closed.”

Tragedy would follow in 1891 with the loss of his son. His performances on the mound plummeted, as a result, combined with an injury. He was reportedly close to signing for the Chicago Colts shortly thereafter “before his wife intervened and said no to the proposed deal”, according to Birch.

In May of 1893, Mullane’s wife of seven years, Barbara, filed for divorce “alleging that he beat her after she criticised his play after a game.

"In turn, Mullane filed for alimony from his wife, saying that she smoked cigarettes, drank beer, and lost much of his money in 'wild schemes.'"

In 1894, his estranged wife accused him of attempted murder after an argument over alimony – and later that year the Chicago Tribune wrote that Mullane had developed a ‘sulky temper’ in Baltimore, and had been sued for $2,000 by a hotel proprietor for hitting him with a baseball bat.

After playing for a few more years in the minor leagues, Mullane finally retired from baseball in 1903. Then, somewhat ironically considering his acrimonious history, he joined the Chicago PD as a complaint sergeant. He suffered a near-fatal abscess of the brain in 1911 but recovered to see out his second career in the force, retiring in 1924.

“If you had mentioned the name Tony Mullane to his team-mates and opponents during his baseball-playing days, many differing opinions of his actions might come to mind,” wrote Birch. “For example, he was handsome and is said to be one of the reasons that ladies’ day games became so popular in the 1880s.

“He was also willing to bend the rules of baseball, pitching above the shoulder at a time when this was considered an illegal pitch; he was also considered to be tight-fisted with his money, often wearing clothes until they became raggedy. But one thing that was universally acknowledged about him was that Tony Mullane was one of the dominant pitchers in professional baseball of his time.”

Mullane’s obituary in the Toledo Blade on Thursday, April 27, 1944, read: “Only a handful of contemporaries remained today to recall the pitching feats of Anthony (Tony) Mullane, whose baseball career spanned a 25-year period from 1878-1903. Mullane, who joined the Chicago Police force when his playing days were over, served until 1924 and he died at home at the age of 85.

“One of the few pitchers to achieve more than 300 victories, Mullane was perhaps the only successful ambidextrous hurler in Major League Baseball history.”

Yet his place in the Hall of Fame remains as elusive as ever. As Irish journalist Dave Hannigan wrote in an article for The Irish Echo newspaper in New York in 2011: “Even though his obituaries 20 years later contained no mention of his prejudices, they may hurt him.

“Last April, baseball’s Veterans Committee placed him on a list of 200 former players who are under consideration for entry to the sport’s distinguished Hall of Fame next year.

“His gaudy statistics make him look like a shoo-in, but the rules expressly state that voters must consider a person’s character and integrity as much as his playing ability. And if they do that, he has no chance.”

Of course, he didn’t. The question remains as to whether he’ll ever fit that bill.

*This article was submitted to IrishCentral by Aaron Dunne, the author of ‘Around The World in GAA Days’ and the upcoming ‘Keepers of the Flame: The Story of Dublin Football’s No 1s’. He is a former Deputy Editor of the Irish Echo in Sydney and is a regular contributor to the Irish Examiner newspaper. You can follow him on Twitter @aaronmcfc1

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments