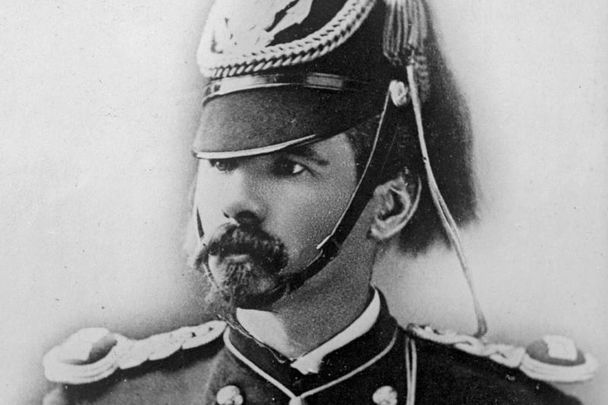

Myles Walter Keogh first served with the armies of the papal states during the war for Italian unification, he then rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the union army during the American Civil war and he was one of 34 Irishmen who fought and died with General Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn on 25th June 1876. His horse Comanche was the only survivor found on the battlefield.

Myles Keogh was born in Orchard House, Leighlinbridge, County Carlow, on 25 March 1840. His family owned a successful farm, and he was one of 12 children born to his parents. While An Ghort Mhor ravaged the land, his family was shielded from the hunger. This however did not stop the young Myles from following the example of millions of his fellow countrymen and women in seeking a new life away from Ireland.

A journey across the Atlantic was not his first adventure, instead, he left for the continent when in 1860 the embattled Pope Pius IX sent out a plea to all Catholics to come to the defence of the Papal States against the forces of Garibaldi and the House of Savoy, who sought to unify the Italian peninsula.

The call roused the sympathies of the Catholic laity in Ireland and across Europe, and hefty donations and eager recruits were quickly dispatched to Rome to defend “the Holy Father” from his enemies.

Alongside 1,400 other Irishmen, Keogh soon found himself in Italy as a member of the Papal Army’s Battalion of Saint Patrick. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant and posted to the city of Ancona after only three weeks of training.

But the reality of his position was not as glamorous as he might have expected. The uniforms the Irish volunteers received were Austrian army cast-offs, while their firearms consisted of obsolete muskets. Despite this, both he and his fellow countrymen were praised by their commanders and fought tenaciously in every engagement and put up a spirited defense of their positions.

The Papal Army as a whole, though, was no match for its nationalist opponents, and the Papal forces were defeated in September in the Battle of Castelfidardo, and Ancona was surrounded. Keogh was taken prisoner but soon released.

Despite his short service, he made an impression on his superiors, and he was as one of only 50 Irish veterans to join the Papal bodyguard’s newly created Company of St Patrick (complete with bespoke green uniforms) and was awarded both the Pro Petri Sede medal for Gallantry and made a Knight of the Order of St Gregory the Great.

Yet the life of a ceremonial bodyguard proved far too tedious for Keogh and with Civil War raging in America, his eyes looked across the Atlantic.

With losses mounting, US Secretary of State William H. Seward began seeking experienced European officers to serve the Union and called upon several prominent clerics to assist in his endeavour.

John Hughes, Archbishop of New York, travelled to Italy to recruit veterans of the Papal War and met with Keogh and his comrades.

In February 1862, Keogh resigned his commission in the company of Saint Patrick and set sail for a brief visit home before making his way to New York. On his arrival in April, he was given the rank of Captain and assigned to the staff of Brigadier General James Shields a fellow Irishman and tenacious fighter, who had been given the remit to seek and destroy the Confederate Army of Stonewall Jackson.

Keogh first saw action when the union forces engaged the Confederates in the Shenandoah Valley and nearly captured the legendary general at the Battle of Port Republic.

During the earliest stages of the engagement, Keoghs mounted patrol came across the staff of General ‘Stonewall’ Jackson camped within the town. Luckily for the Confederate general, his horse was saddled nearby, and he was able to make his escape, though many of his senior officers weren’t so fortunate and were taken prisoner by Keogh and his men.

Keogh's bravery during the campaign drew the attention of George B. McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, who described Keogh as: "a most gentlemanlike man, of soldierly appearance," whose "record had been remarkable for the short time he had been in the army."

McClellan was so taken by Keogh that he was temporarily transferred to his personal staff and served the General during the Battle of Antietam.

After McClellan was dismissed by President Lincoln in November 1862, Keogh and his Papal comrade, Joseph O'Keeffe, were reassigned to General John Buford's staff.

Buford, a cavalry commander with whom Keogh formed a close bond, affectionately referred to his Irish officers as “dashing, gallant and daring soldiers”.

Keogh fought bravely at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862 and the Chancellorsville campaign from Apr 30th - May 6th, 1863.

On June 9th, 1863, now an experienced Cavalryman, Keogh took part in the battle of Brandy Station the largest cavalry engagement ever to take place on US soil.

Myles continued to fight with distinction throughout the remainder of June 1863 as the 1st Division of Union cavalry skirmished with Confederate forces, commanded by J.E.B. Stuart in Loudoun County, Virginia.

Then in July 1863, his bravery at the battle of Gettysburg saw him receive promotion to the rank of major for "gallant and meritorious services”.

Major Keogh was appointed as aide de camp to General George Stoneman. In July 1864.

General Stoneman said of Keogh: “Major Keogh is one of the most superior young officers in the army and is a universal favourite with all who know him”.

Stoneman and his men carried out daring raids behind Confederate lines to destroy railroads and confederate industrial infrastructure. They also planned to liberate federal prisoners held at Macon, Georgia, and the nearly 30,000 inmates of the infamous Andersonville prison.

On the 31st of July 1864, Keogh was captured along with Stoneman by Confederate forces who shot their horses from under them.

Myles spent two and half months as a prisoner of war before being released in an exchange arranged by Union general William Tecumseh Sherman.

Keogh went straight back into battle and was promoted once again to lieutenant colonel for his gallantry during the battle of Dallas in June 1864.

Myles would end the war as Brevet Lieutenant Colonel, and he chose to remain on active duty and accepted a Regular Army commission as a second lieutenant in the 4th Cavalry on 4 May 1866.

On 28 July 1866, he was promoted to Captain and reassigned to the 7th Cavalry at Fort. Riley in Northeast Kansas where he took command of Company I.

George Armstrong Custer was the regiment's Lieutenant Colonel and its deputy commander.

Keogh was generally well-liked by fellow officers although the isolation of military duty on the western frontier often weighed heavily upon him. When depressed he occasionally drank to excess, though he seems not to have fallen prey to the chronic alcoholism that destroyed the careers of many fellow officers on the lonely frontier.

In the summer of 1874, Keogh went on leave to visit his homeland on a seven-month leave of absence, while Custer was leading a controversial expedition through the Black Hills. During this holiday he deeded an inherited estate in Kilkenny to his sister Margaret. He enjoyed his stay in his homeland, feeling the necessity to support his sisters after the death of both parents.

In October, Keogh returned to Fort Abraham Lincoln to link up with Custer for a new campaign against the native Americans.

As a precaution, he purchased a $10,000 life insurance policy and wrote a letter of warning to his close friends in the Throop-Martin family, in Auburn, New York, outlining his burial wishes: “We leave Monday on an expedition & if I ever return, I will go on and see you all. I have requested to be packed up and shipped to Auburn in case I am killed, and I desire to be buried there. God bless you all, remember if I should die—you may believe that I loved you and every member of your family—it was a second home to me”.

He gave out copies of his will to comrades and left behind personal papers with instructions that they be burned if he was killed. His apprehension was well-founded given the heightened tensions in the west.

Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, leaders of the Sioux nation on the Great Plains, strongly resisted the efforts of the US Government to confine their people to unsuitable reservations.

After the US army invasion of the Black Hills area of Dakota after gold was discovered, many more Sioux and Cheyenne tribesmen angered at this incursion into what they perceived as sacred territory left their reservations to join the growing resistance of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse in Montana.

By the late spring of 1876, more than 10,000 Native Americans had gathered in a camp along the Little Bighorn River. This was in defiance of a U.S. War Department order to return to their reservations.

When a federal deadline to move to reservations expired, Custer and his 7th Cavalry, was dispatched to confront them.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, fought on June 25, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory, pitted federal troops led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer against a band of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. Custer was unaware of the number of Indians fighting under the command of Sitting Bull at Little Bighorn, and his forces were greatly outnumbered and quickly overwhelmed in what became known as ‘Custer’s Last Stand’.

Myles Keogh may have had a premonition of his death when organising his will and sorting out his life insurance and he was the only Irish officer to take part in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and apparently one of the last to fall.

When the defeat was discovered and the sun-blackened and dismembered dead were buried three days later, Keogh's body was found at the centre of a group of troopers that included his two sergeants and company trumpeter. His body was stripped but not mutilated, perhaps because of the "medicine" seen in the Agnus Dei ("Lamb of God") he wore on a chain about his neck.

Keogh's left knee had been shattered by a bullet that corresponded to a wound through the chest and flank of his horse, indicating that horse and rider may have fallen together prior to the last rally.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

His horse, Comanche, was the only injured animal the rescue party spared, and after he was nursed back to health, was adopted as the regimental mascot of the 7th Cavalry which he remained until his death in 1890.

Originally buried on the battlefield, Keogh's remains were disinterred and taken to Auburn, as he had requested in his will. He was buried at Fort Hill Cemetery on 26 October 1877, an occasion marked by citywide official mourning and an impressive military procession to the cemetery.

On his grave there is an inscription taken from the poem, The Song of the Camp by Bayard Taylor: "Sleep soldier still in honoured rest, your truth and valour wearing; The bravest are the tenderest, the loving are the daring."

The marble cross atop his resting place was added later at the request of his sister in Ireland.

Tongue River Cantonment, in south-eastern Montana, was renamed after him to be Fort Keogh.

Myles Keogh travelled far from County Carlow serving in Europe and across America and was recognised wherever he went as a brave and valiant warrior and fine human being.

Not a bad legacy to leave behind after such a short life.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments