“And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And 'Thou shalt not' writ over the door”

—William Blake’s ‘The Garden of Love’

The Belleek Community is currently waiting for the planning decision from the Fermanagh and Omagh District Council to see if Keenaghan Abbey and graveyard in Co Fermanagh will be protected. The latest development is that the landowner has blocked public access to the abbey and graveyard and locked the gate shut for the first time since the 17th-century Penal Laws in Ireland.

Residents in Belleek are forbidden from paying their respects to the Irish heritage site, which is one of the oldest churches in Ireland. Keenaghan Abbey and graveyard are already currently under attack from the proposed development of a glamping pod site with large amenity buildings and a car park for almost 100 vehicles that will destroy the natural environment and desecrate the historic landscape. Blocking public access to the abbey and graveyard and locking the gate shut is now another attack on Belleek families and on Irish history.

According to Belleek historian Joe O’Loughlin: “Keenaghan Abbey had for several hundred years been the focal point for Christianity in the Ancient Kingdom of Mulleek. This sacred place with the a-joining walled cemetery alongside Keenaghan Lough has a long history” dating to the sixth century.

“Following the Plantation of Ulster in the early 1600s, Cromwell’s forces destroyed” the four abbeys in the area. However, “the east wall of Keenaghan with its unique ‘Candle Window’ survived the destruction.”

Keenaghan Abbey and graveyard historically bridge the religious divide in Northern Ireland because as Joe states: “For generations, locals from both Catholic and Protestant areas were buried in Keenaghan.”

Access has always been granted to the Christian faithful by the prior landowners because they understood that Keenaghan is a sacred place. Now many parishioners of St. Patrick’s Church and Belleek’s Parish Church believe that it is a deeply unchristian act for this current landowner to block public access to the abbey and graveyard and to lock the gate shut.

For 92-year-old Joe O’Loughlin, it is undoubtedly personal for him and his family as he is forbidden from paying his respects and honoring his family in the graveyard. His great-great-grandfather, Barney Loughlin, and his great-great-grandmother, Lisa Coyle, of Druminillar and Commons are buried in Keenaghan in Section B, Plot 9. Barney and Lisa's headstone was erected by Joe's parents, John and Katherine.

In Joe’s "Ancient History of the O’Loughlin’s," he recounts the O’Loughlin relationship to Keenaghan and poetically describes the importance of Keenaghan to the Belleek community:

“Thanks to the willingness of local residents this graveyard took on a new lease of life. In the spring of 1965 Tommy O’Loughlin from Belleek whose ancestors are buried in it, organised a group of local men, who stepped in and did a wonderful job. They came, the men with the scythes and hooks, weather beaten outdoor men, who worked steadily at their pace. With the aid of edged tools and with the determination of those who worked the field, the task was undertaken. The crack of blade on stone; brought forth blessings on the dead, uncovering the resting place of old friends and of long forgotten families. It stirred memories of a past age, recalled the wit and fun of other days. The moon rose above the eastern gable wall with its unique stone window frame, designed to give the maximum of natural light to the interior of the building. Order was restored and headstones stood proud and free, the living giving dignity to the dead.”

Regarding the development, Stephen Heron from the Belleek History Society states: “The developer has said that the reward of letting this proposed monstrosity happen is that we will get back access to Keenaghan Abbey and graveyard, that is on his land.

"There had never been a problem till he acquired the land, and what he may not understand is that we have rights.

"The Abbey, the good people buried there, and the public access, did not just appear after he acquired the land, they have been there for centuries and will be there long after we are all gone.”

The landowner, who is also the developer, has now publicly contradicted himself because he has absolutely no intention to allow access as he has just blocked the only public access, which has been there long before the landowner’s family settled in Ireland during the Plantation period.

The Historic Environment Division (HED) states that: “the rural character surrounding the abbey is a critical aspect of how it is experienced, understood and enjoyed," and that the abbey: “Is also publicly accessible, signposted and included on tourist and heritage information for the area.”

Not only has Keenaghan Abbey and graveyard been blocked and locked, but “the previous signpost to the abbey is no longer in situ."

By shockingly tearing down the signpost, the landowner is desperately trying to erase Irish history just as Cromwell’s forces razed the four other abbeys to the ground. The Belleek community is targeted by the threat of this monstrous, large-scale development.

Stephen Heron, who is speaking on behalf of not just Belleek, but for any small town, Irish communities asserts that: “We have the right to use it, and it is not a privilege granted by the new landowner. Once a highway—always a highway!”

Keenaghan Graveyard is an ancient library of Fermanagh and Irish history. From the Catholics and Protestants who are buried there side by side, to the old monks who founded the church, there are Fenians, farmers, labourers, and gentry from all walks of life united within these hallowed walls.

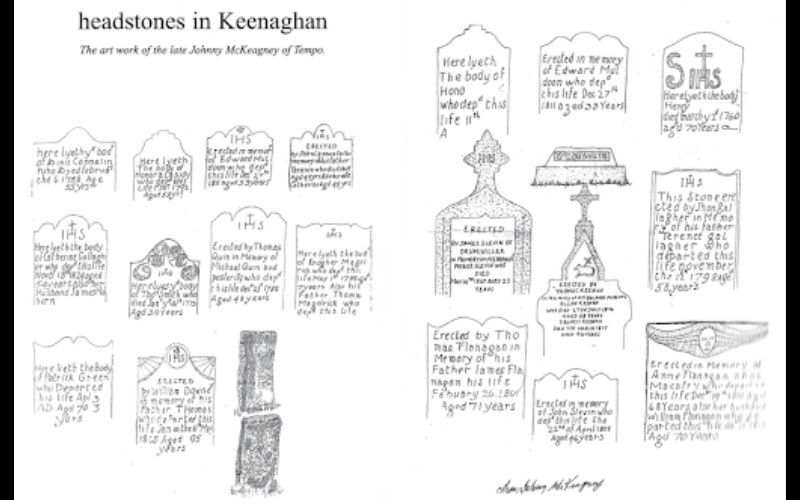

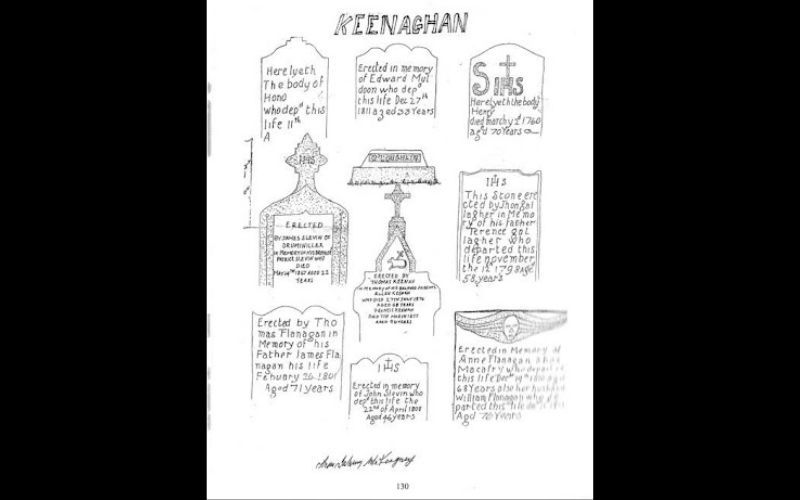

Fortunately, the remaining headstone names were verbally recorded by Joe O’Loughlin and visually represented by the artwork of the late Johnny McKeagney of Tempo.

Each one of these headstones is more than just a carved name and engraved year of death—each headstone is an inscribed book in Keenaghan Graveyard and tells a remarkable life story.

Thanks to Stephen Heron and Joe O’Loughlin, we can tell some of these stories:

In Section B, Plot 3, we find the headstone of Dennis Greayson (Greyson): “Sacred to the memory of Denis Greayson. Died 11th Nov. 1813 aged 57 Years. (Q. & M.N.).”

Born in 1756, two years before the first repeal of the Penal Laws, Dennis was an influential figure from an old and respected family. The Greysons of Belleek were farmers and businessmen, as well as renowned leaders of a political race. Dennis's father was more than likely the Edward Grayson who appears in the Catholic Qualification Rolls living in Belleek and working as a shoemaker in 1780. One of Dennis's descendants, another Dennis, was “prominently associated with the Ribbonmen and Fenians of the district”. He was a supportive and well-liked character who believed in helping prisoners fight their injustices by offering to provide funds for their offenses. These descendants of Dennis buried here in Keenaghan reflect the morality and integrity of the Greyson family.

My great-great aunt, Bridget Keenaghan, married Edward Greyson, the son of Patrick Greyson, from the Knather in Ballyshannon. One story that was passed down to me about the Greyson family is that my great-great grandad, 'Black' James Keenaghan, worked with many other Belleek labourers in Greyson's large lime kiln and quarried the stone from Greyson's Quarry for the construction of St. Patrick's Church in Belleek, 1892.

In Section B, Plot 6, we find the headstone of Patrick Slevin.

Born in 1845, two years before the Famine of Black '47, Patrick was a member of the Fenian Brotherhood who fought for Irish Independence. He was “sworn into the Fenian Brotherhood by a Druminillar man— Hugh Montgomery—the Centre leader at the time as well as a poet of high repute. After some time the Belleek R.I.C. began to hunt and hound the young freedom worker”. Patrick was arrested for an illegal assembly during Ballyshannon Fair Day, which unfairly led to his imprisonment.

Although he was “Broken in health, but not in spirit, his captors cast him out on the streets, and he was taken back home by his people to die. By his life he forged one of the strongest links in that endless chain of Irish resistance to British rule. By his death he gave us a Fenian grave." His memorial was erected in the centenary of his death by Fermanagh Republicans, and on his plaque the engraved patriotic epitaph reads "1867-1967. In remembrance of Patrick Slevin, aged 22 years. Member of the Fenian Brotherhood, who died as a result of ill-treatment in jail on May 14th, 1867. Remember them with pride. R.I.P.”

In Section D, Plot 5, we find Francis Keenan's family headstone.

Francis has quite the fascinating story because he literally swam out of Ireland at the age of 14 into exile because he was falsely accused by constables of poaching. His great-granddaughter, Patricia Brooks, wrote his story in the New Zealand Tablet, detailing his journey to Scotland and Australia and then striking gold in New Zealand. Francis "found a gold nugget the size and shape of a baby's heel. For years after, goldminers were said to be looking for the other heel” of Francis’ baby.

Although Francis never returned to Ireland, he did send money home for a church to be built after his mother, a Freeburn died—this church was St. Patrick's in Belleek built with the Greyson’s quarried stone. 148 years after Francis Keenan’s sudden departure from Irish shores, his great-granddaughter, Patricia, found the family grave of his parents in Keenaghan and expressed "Here was a little bit of Ireland that was ours!"

Francis’s brother, Thomas, struck gold and sent money home to Ireland to have a large marble headstone erected: “I.H.S. Erected by Thomas Keenan in memory of his beloved parents, Ellen Keenan, who died 27 March 1874, aged 68 years. Francis Keenan, Died 7 March 1877, aged 96 years. (J.McC., Q. & M.N.)"

As Francis’s great-granddaughter stood by the family headstone, she “thought of the parents' loneliness not knowing of their sons or ever expecting them to return from the other side of the world". Francis Keenan’s family headstone is a touchstone for how the historic graveyard of Keenaghan has had a profound resonance with families throughout the wider world.

However, as Stephen Heron states, “Not all the resting places in the graveyard are marked with headstones”. One of the resting places with no headstone belongs to Mr. James McHugh from Belleek who died on the 24th May in 1882. His character, funeral, and burial at Keenaghan is accounted for in his obituary: “On last Sunday the remains of the above highly respected and generally-esteemed old gentleman were interred in Keenaghan graveyard a locality distant from Belleek about two miles, and a spot whose present aspect eloquently attests the accuracy of the tradition which invests the adjoining ruins with deeply-cherished and hallowed significance." It is also notable to point out that “the funeral cortege, which was the largest and most representative ever seen in this district, proceeded to Keenaghan, the place of interment" from Belleek.

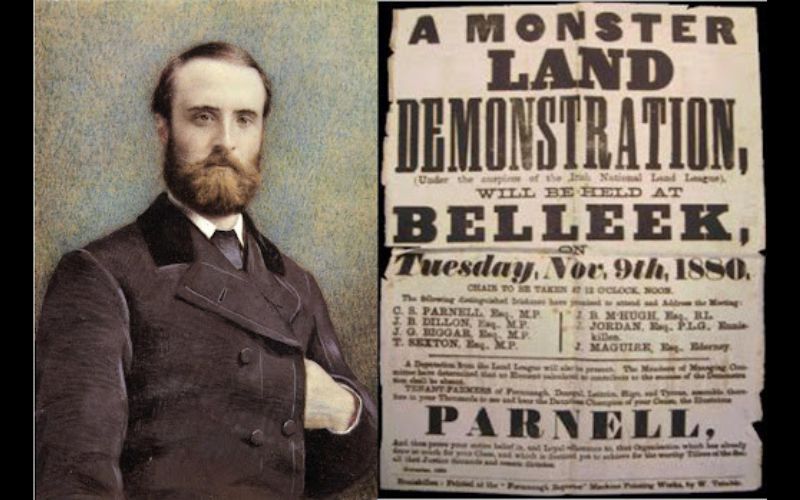

Mr. James McHugh was the old gentleman who first hired my great-great granddad, ‘Black’ James Keenaghan, as a car driver and labourer for McHugh’s in Belleek in 1873. Mr. McHugh and his son, Arthur, the Local Secretary of the Irish National Land League, were instrumental in organizing the meeting and speech of Charles Stewart Parnell in Belleek in 1880. An audience of nine thousand attended the ‘Monster Land Demonstration’ on a meadow that was kindly granted to the Land League by Mr. Johnston of Johnston’s Hotel in Belleek.

Although these life stories are only a brief selection from the earthy shelves in the stone-library that exists in the graveyard, they all ultimately cornerstone the historical significance of Keenaghan Abbey and Keenaghan Graveyard. The unique east wall, which symbolically represents the last Irish stand against Cromwellian forces, has stood there defiantly through it all.

As every headstone speaks its story, the east wall speaks its story, too—what Keenaghan’s sacred stones must say is that no matter if the abbey and graveyard are blocked—no matter if the gate is locked— its candle sculpted window will still shine its eternal light over all those unknown and known that are buried therein under the abbey’s candle-stone such as the Mc Goldricks, Quins, Magee’s, Garvin’s, Doherty’s, Slevin’s, Downey’s, Green’s, Barron’s, Mulrone’s, Muldoon’s, Greayson’s, Loughlin’s, Mc Laughlin’s, Gallagher’s, Cassidy’s, Donagher’s, McAwley’s, Smith’s, Lannon’s, McGarrigle’s, Mc Gurran’s, O’Neil’s, McCaffrey’s, Keenan’s, Flanagan’s, Higgin’s, Conner’s, Tuthill’s.

Let us call the candle-stone window on the east wall—An Coinneal-Cloiche—An Coinneal-Cloiche stood there dignified yesterday, stands there proud today, and will stand there tomorrow free—a solitary soul illuminated every morning by the dawning light rising brightly through Keenaghan and brightly rising— An Coinneal-Cloiche—guardian of the soul-stories by the graveyard’s green grassy dew— let us imagine we stand in solidarity— with An Coinneal-Cloiche too.

Comments